NT schools run by remote control from Darwin’s ‘Carpetland’

Where is more than half of the NT’s $1.179bn education budget if it’s not being spent on schools? The answer is buried somewhere on the 14th floor of a Darwin office building people call ‘Carpetland’.

What happens to more than half of the Northern Territory’s $1.179bn education budget is information buried somewhere on the 14th floor of a Darwin office building people refer to as “Carpetland”.

The NT Department of Education’s airconditioned offices are a long way from the on-the-ground realities of remote schools. With a supermarket, jeweller and sushi place in the shopping centre below, public servants are at a distance from the remote teachers who sometimes drive through several croc-infested creek crossings to reach their students.

Educators have told The Australian this is a problem because the department has the most power to decide where the money is spent.

Of the 2021-22 NT education budget, less than half ($558.5m) went directly to schools, according to government data released in response to a parliamentary question in writing. The remaining $620.5m was managed centrally.

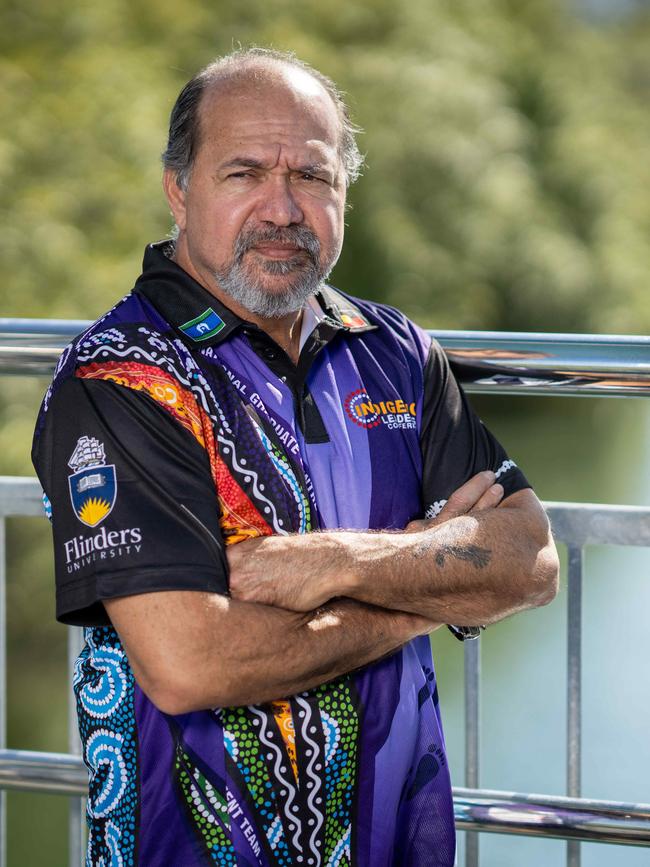

“It’s just not a good look” is how John Guenther, research leader for education and training with the Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education, describes the breakdown of spending.

As The Australian has reported, schools across the Territory are the most underfunded in Australia, and many are cutting essential programs and teachers.

“The allocation to corporate services has been increasing well above the inflation level,” Guenther says. “And I don’t see that there is any sort of justification for that because they’re not actually providing any more service.”

It’s hard to ascertain the size of the NT Department of Education, which classifies its bureaucratic or “corporate” staff as “non-service based” and its on-the-ground staff, such as teachers, as “service-based”. The distinction is not clear because some staff work across both categories.

According to the department’s 2021-22 annual report, of 4400 positions, 483 (11 per cent) were non-service based.

However, 2022 Productivity Commission data, which uses a different classification, shows 704 staff “not active” in NT public schools. Analysis by the Australian Education Union NT reveals that for every 1000 students, the NT has 24 non-school staff, compared with nine in the ACT and eight in Tasmania (other small jurisdictions).

The Australian Education Union NT also reports Territory Department of Education spending on non-school staff rose 81 per cent between the 2015 and 2020 financial years, to $123.1m.

At a Darwin press conference this week NT Chief Minister Natasha Fyles defended the size of the bureaucracy, saying: “In terms of our agencies, we need to make sure that they have the support to do their job. If we can have people out of agencies and on the ground in schools, that’s absolutely what I want to see. But we, as a government, have certainly invested back into schools, more teachers in our classrooms, more resources for our teachers and more infrastructure for education.”

The NT Education Department says central and corporate spending does funnel into schools, directly and indirectly. It covers costs for things such as principals’ salaries, some staff leave entitlements and allowances, and urgent minor repairs or new works.

In a jurisdiction such as the NT, which has many small and remote schools, it also can make sense to centralise some services; for example, counsellors or health workers who support more than one school.

NT Education Minister Eva Lawler says education is a fundamental human right.

“We fight every day to ensure all students in the NT, no matter how remote they live, have access to a quality education,” she says.

“We have placed high importance (on) ongoing monitoring and accountability mechanisms to track progress and ensure that human rights in education are respected and protected.

“We are working with stakeholders and community groups to ensure that families understand every child has equal access to a quality education here in the NT and that education is the key to removing barriers for success – whatever that success looks like for each individual.”

Accusations of a “bloated bureaucracy” at the cost of essential programs have been longstanding and on both sides of politics.

Former NT Indigenous policies and programs analyst Shane Motlap says a report on the Territory’s educational outcomes in the 1990s should have been a turning point for schools. Instead, all it did was further inflate the bureaucracy.

“It spelled out very, very clearly the literacy and numeracy levels of First Nations people in the NT – it was alarming,” says Motlap, a Mbabaram man. “And because you’ve got public servants in the system, they will do what public servants do, and they will build bureaucracies … that do very little in getting good outcomes or turning around some of the sadder stories.”

He found that it wasn’t uncommon for good programs to be shelved because the government had “run out of resourcing”.

“Good things don’t last up there,” he says. “The good programs go well and then they die. And then I’d ask questions: what do you mean ‘run out of resourcing’?”

Motlap says resources run out because the funding for any program also needs to support the high bureaucratic spending to deliver it.

Former NT principal and Indigenous education academic Gary Fry says the generalised pooling of funds also has hindered transparency around spending.

“What it’s created is this monster, where people are just basically using Aboriginal people for political reasons, putting their hand out for the money, and then just absolutely not accounting for the way that money has been expended,” says Fry, a Dagoman man.

“We can’t continue to do this. The Australian public has been given a disservice of the biggest magnitude, it’s hidden in full view of everyone.”

‘Cash cow’

Fry was one of the NT’s most senior Aboriginal principals and has a national reputation for his work in challenging schools. But he relocated to Townsville in North Queensland in part because of “systemic and institutional racism” in the NT education system.

He says the problems in NT schools could be fixed, but he’d also seen an “acceleration of marginalisation” in the Territory, despite the enormous funding commitments. He did a PhD to find out why.

“My whole experience was just seeing just how deeply embedded and interfering the political system of the Northern Territory was in its key institutions, in this case education,” he says. “I saw so much just bad practice. I saw so much privileging of people who just should never have been privileged.”

He says his PhD, which won the University of Sydney medal, found there was a strategic answer to many of the issues affecting education in remote areas: to listen to the people on the ground, including First Nations students, teachers, principals and advisers.

“A lot of this carnage in education policy dysfunction can be solved,” he says. “Basically, do away with the model of bureaucracy.

“The Education Department has become a cash cow really for a small group of people who have just been sponging off it. These are the people who are the nameless, blameless beneficiaries of structural inequality. Aboriginal people have always wanted to be part of a change. But they have not been able to under this oppressive political economy. Those people have done untold damage.”

Urban bias

Rolf Gerritsen claims to have the “skin of a turtle” – a protective mechanism the Charles Darwin University political economist, who used to be a senior economist in the NT chief minister’s office, says he developed after 15 years of trying to work out what happens to public spending in the Northern Territory. “The Territory has basically become a public service state, which is run by and on behalf of the public service,” Gerritsen says.

“Ultimately, the (NT) public service, instead of being 24,000, should be about 14,000, and all these managers and supervisors and whatever are redundant to purpose.”

The self-declared “equal opportunity annoyer” says the Territory’s high bureaucratic spending compared with other jurisdictions has happened on both sides of politics and within a range of departments. He also claims the “top-heavy” bureaucratic structure distributes the workload unevenly.

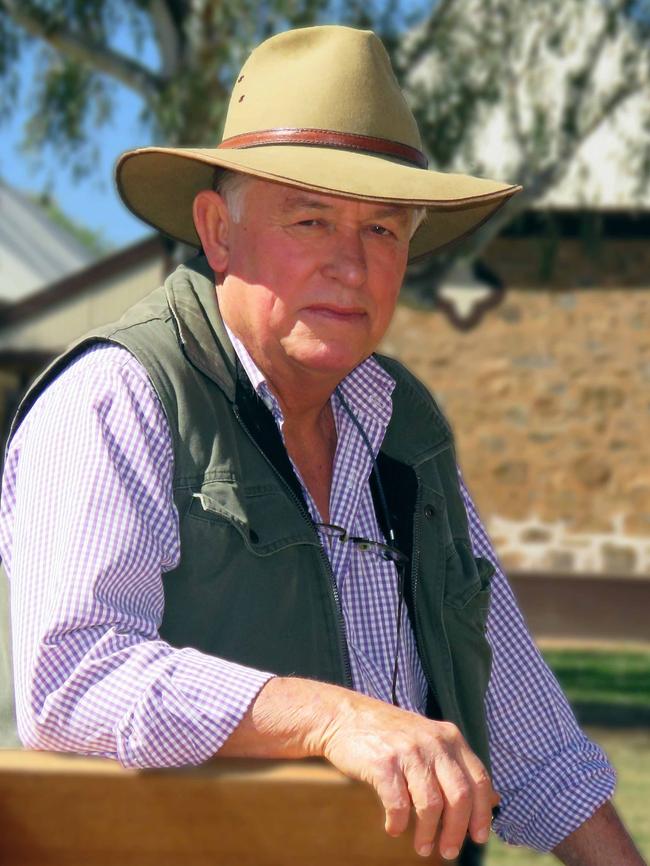

Former senior NT public servant Bob Beadman, who also worked with the federal department of Indigenous affairs, agrees the NT has “an excessive number of senior executives”. “Everybody knows that the Territory public service is bloated to buggery,” he says.

According to Gerritsen, high bureaucratic spending is one of many ways public funds are channelled away from remote areas and into the capital. His research found a third of the money allocated to the NT on the basis of Indigenous disadvantage is spent in the Darwin-Palmerston area, based on how GST revenue is distributed.

The NT gets about $3.8bn a year from national GST income, a larger per capita share than the states to help support the high cost of delivering services in remote areas with high levels of disadvantage. Gerritsen says for every 80c NSW receives, the NT gets about $4.80.

“There’s no requirement on the recipients of these general purpose grants to do anything in particular with them,” Gerritsen says.

While GST allocations to each state and territory are intended to provide services and infrastructure – such as health, education and housing – in the NT, Gerritsen says, large portions end up supporting projects designed to appeal to voters in the Darwin-Palmerston area. Across past decades, for example, $80m has been spent on boat ramps for recreational fishing.

Beadman lists other examples of extravagant spending: $12m for a grandstand at the Darwin Turf Club, $10.5m for a new police station at Nightcliff, and the Darwin waterfront precinct, which cost $200m.

He says this spending is at the expense of much-needed infrastructure such as schools in remote communities. “We’ve got a history now of decisions that are so glaringly bad that if a chief minister went into a premiers conference and argued for a greater share of the GST, they would be laughed out of the room,” he says.

Beadman says although governments consistently report Indigenous expenditure that looks generous, these figures “require dissection”. For example, because 95 per cent of the NT’s prison population was Aboriginal in 2019, 95 per cent of the corrections budget – and its bureaucratic workforce – was counted as Indigenous expenditure.

“That budget includes rental of office accommodation in town, probably with a harbour view, a CEO sitting at a lovely desk in a palatial office with a taxpayer-funded car and all of the side benefits that go with it,” he says.

Gerritsen says the “urban bias” in NT spending is “completely political”, whichever party is in power, because more than half of the NT’s electoral seats are in the Darwin-Palmerston area. “Darwin basically decides elections … so those voters, they’re very important,” he says.

Moreover, the Territory’s remote seats are all safe, says Gerritsen, so “they don’t have any electoral currency”.

“The simple fact is the Territory state exists because of Aboriginal disadvantage, and it has an incentive not to ameliorate that disadvantage because then it will get less money from the commonwealth,” he says. “So the disadvantage becomes permanent.”

In 2019, the Yothu Yindi Foundation described a system of government and administration “close to breaking point” in a submission to the Productivity Commission.

“The system in the Territory is so out of order that it has turned in upon itself, such that the low socioeconomic conditions of remote Aboriginal Australia have become the means by which the system maintains itself,” the report said.

Foundation chief executive Denise Bowden says the scale and structure of the bureaucracy was a major part of the foundation’s decision to pursue an independent schooling model. “The moment we saw inside the system, we very quickly backtracked because we could see the inflexibility of it, the rigidity of it,” she says.

She says independent schools and non-government organisations have to report where public funding is spent.

“We want that same accountability with government,” she says. “There’s no real will to unpick this because the moment you start unpicking it is when everyone goes, ‘Oh my God, this is actually bigger than I thought’ or ‘It’s too hard to fix’. We call for systemic reform. Unpick it, please. Open your books and talk about how you’re going to fix this.”

$6.5m shortfall

Nine hours’ drive from Darwin’s Carpetland, in the central Arnhem homeland of Gochan Jiny Jirra, it’s after dark when Garth Doolan and his family arrive clutching a huge, fresh-caught goanna. Kids are playing footy under a string of festoon lights while dinner is cooking. In the glow of the campfire, women chat while a fish is cooked. One woman is playing Homescapes on her phone, another is scrolling on Facebook. Almost all of the other adults are watching a football game in a house near the empty school.

As revealed by The Australian, Gochan Jiny Jirra is one of the many communities that has a registered teacher only part time because of its classification as a Homeland Learning Centre. HLCs are considered classrooms attached to a hub school in a larger community.

When Doolan hands over the goanna, there’s a brief debate about who should remove the entrails. Eventually Dorothy Galaledba, an acclaimed artist whose paintings have been exhibited at the National Gallery of Australia, agrees to do it, and everyone admires her surgeon-like precision.

Another woman aims her phone at the goanna, shining a light on its speckled body as Galaledba turns it over in the flames. Its feet curl up as it cooks.

Doolan, Galaledba, the women around the fire, the kids – everyone in Gochan Jiny Jirra is used to navigating two worlds. Doolan knows how to catch freshwater catfish using a hook he makes from ironbark, just as he knows how to apply for a grant and argue with politicians. He’s happy to walk in both worlds but he’s not sure it’s a two-way street.

Despite dire conditions in many HLCs – some don’t have power or water – their students do attract substantial funding. However, the federal funding travels to a pool administered by the NT government, which applies an attendance-based model that in many cases reduces the money schools are entitled to receive. Then the funds are distributed to a hub school managing the HLC. Maningrida College, which manages 13 HLCs including Gochan Jiny Jirra, received less than half (49 per cent) of its $12.7m allocated income, a $6.5m shortfall. Sources have told The Australian many hub schools are so underfunded they can’t fund their own operations, let alone the costs of HLCs.

What Doolan wants is simple: full-time education, the same thing kids in Sydney get. But most of the money the children at HLCs are supposed to receive for their education never makes it to homelands such as Gochan Jiny Jirra.

Inappropriate spend

Remote teachers and principals say the distance – physical and ideological – between Carpetland and remote communities means even when funding does make it into remote areas, often it ends up in the wrong places.

Former remote principal Leon White says his time working for the department in 2019 revealed few bureaucrats had backgrounds in education and even fewer had experience in remote areas. “There was not one person on the 14th floor who had worked as an educator in a remote community in the Northern Territory,” White says.

Many remote teachers have told The Australian that a British reading program that teaches phonetics instead of letters has left children unable to spell their own names. One teacher gives the example of a remote Indigenous class, where English is not the first language, being taught to read using books with words such as “lorries” and “vests”.

Several educators say direct instruction, a US program rolled out in 19 very remote schools until 2019 and costing $25m to $30m, was inappropriate for the context.

“All these schools were broke and struggling to staff their classrooms, and these (direct instruction) coaches were being flown in from the US to work in remote schools,” says one teacher, who cannot be named. “If only they had spent that money on Aboriginal teachers’ training.”

“There was no consultation with community,” says former department deputy chief executive Kevin Gillan, who believes direct instruction was “key in attendance falling off the cliff” in the communities that used it.

“(The Department of Education) runs everything on a template, a one-size-fits-all approach, but in the NT every remote community is a different nation with a different language,” Gillan says. “What we really need is a place-based approach.”

Aboriginal affairs advocate Mark Motlop was the inaugural chairman of the Northern Territory Indigenous Education Council, a body established with a direct reporting line to the education minister. The council’s role was to consult with communities and advise on education policy, but Motlop says the government “wanted a helicopter view of the world”.

“We interviewed communities when we travelled and they wanted all these small things fixed first,” he says. “Little things, like perhaps a bus to pick kids up to go to school, or get the roads fixed so they can be accessed by people to bring their kids to school. Breakfast programs, little things like that.

“Government didn’t want the small things. They just don’t get it.”

Of the 56 recommendations the council made, only one was implemented. “I just get angered when I think about it,” Motlop says. “They don’t listen to the people that are there. People can walk a million miles in Aboriginal people’s shoes, but they’ll never, ever, ever get it.”

Retired principal and former Australian Education Union NT president Stephen Pelizzo spent almost 35 years as a teacher and principal across the Territory.

“In my later years as a principal, I spent more time fielding compliance questions from the department than I did dealing with children and teachers,” he says. “The bloated bureaucracy comes with its own costs, it gives people things to do.”

The real cost of the system, he adds, is that it’s so rigid it doesn’t allow for innovation.

“Education is by its nature at its best when there’s a certain level of risk involved,” he says. “Even kids learning to read – they make that leap of faith about the next word. It’s a central part of good learning. But we’ve set up a system where everybody from the top down is as risk-averse as possible. And being risk-averse means that you don’t succeed.”

Even after retirement, Pelizzo still gets emotional talking about the way funding and decision structures have limited what schools can do in remote communities.

“I know that Aboriginal people love their kids,” he says. “They want the best for them. They want the best in education, both in their way and our way. But we just seem to have set up a whole system whereby we stare at our own feet. We stop ourselves from doing good things.”

Caroline Graham and Kylie Stevenson are independent journalists working in the Northern Territory and Queensland. This project was supported by the Meta Public Interest Journalism Fund.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout