Mona and Cindy: 32 years a lonely road to justice for Bourke teens

Decades after a man accused of killing two girls – molesting one of them as she lay dying – walked free, a long-held wish has been granted.

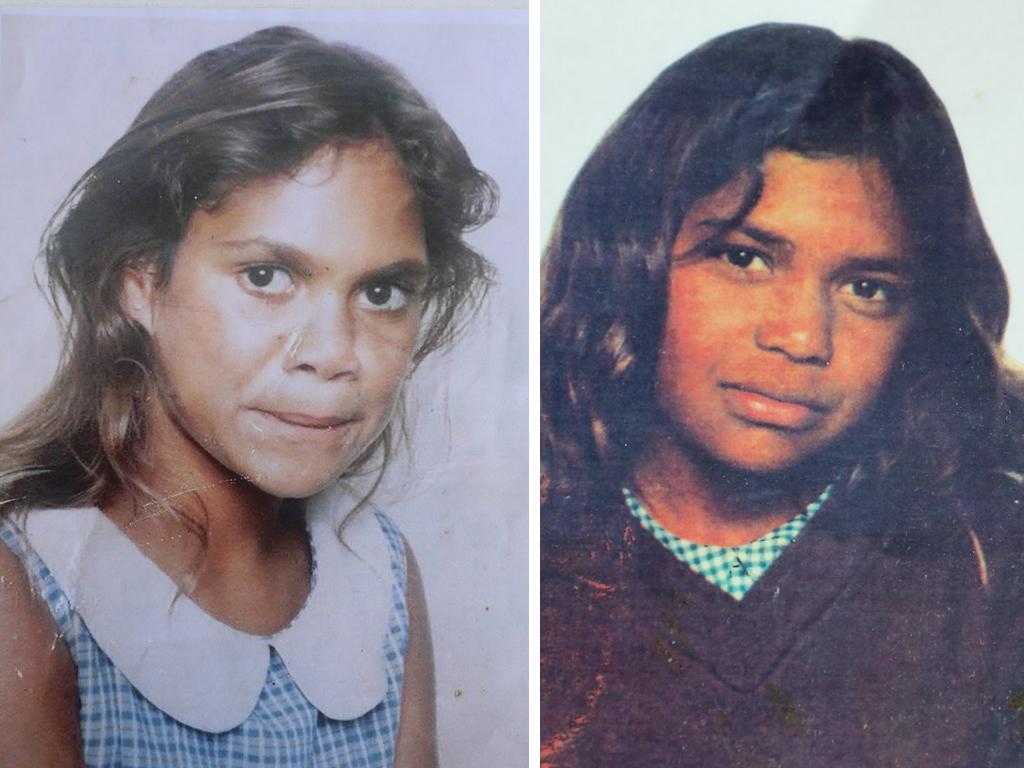

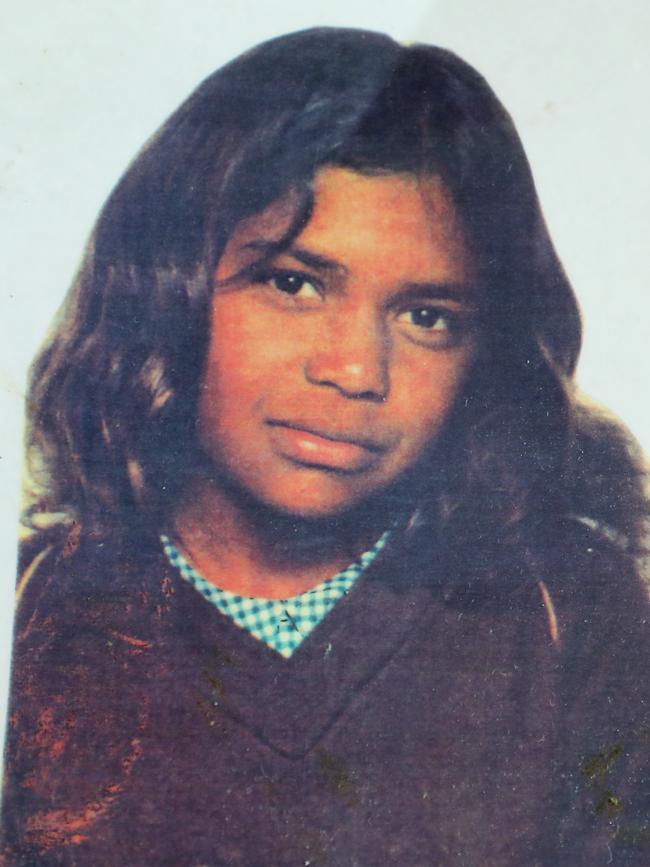

Thirty two years after a man accused of killing two Aboriginal girls – and molesting the critically injured younger child – walked free from a court in Bourke, NSW, the grieving families’ long-held wish has been granted: a full inquest will be held into the children’s horrific deaths. This legal breakthrough follows a decades-long quest for answers into why no one was ultimately held accountable for the deaths of the two Bourke teenagers, Mona Lisa Smith, 16, and Jacinta Rose Smith, 15, who accepted a lift from a 40-year-old white excavator driver in December 1987 and never returned home.

The inquest is likely to probe criticisms of the police investigation and legal prosecution of the defendant, who never spent a day in jail in relation to the girls’ deaths, despite admitting he had lied to police. The inquest may also highlight the fractured relationship between law enforcement and Bourke’s Indigenous community at the time.

June Smith, Mona’s 73-year-old mother, described the decision by NSW State Coroner Teresa O’Sullivan to complete an inquest as “the most beautiful news I’ve heard in a long, long time”. Dawn Smith, Jacinta’s 80-year-old mother, said she was “very happy” that through the inquest – which was begun in 1988 but suspended for legal reasons – “the truth could be told”. She said there had been so many setbacks in the Bourke families’ 35-year quest for justice, “I just gave up hope that we would even get it reopened’’.

In December 1987, Mona and Cindy, as she was known to friends and family, climbed into a Toyota HiLux driven by excavator driver Alexander Ian Grant. Hours later, Grant’s ute skidded, crashed and rolled north of Bourke and both girls, who were cousins and close friends, were killed. Mona lost an ear and was partially scalped while Cindy suffered massive internal injuries and a broken pelvis.

Yet Cindy was found at the crash site in a near-naked state lying next to Grant, who was drunk, unhurt and had his arm across her exposed chest. Cindy’s pants were pulled down to her ankles and her top was pulled up under her chin, sparking allegations she had been sexually abused by Grant as she lay dying or dead.

Grant was charged with culpable driving causing the death of both girls and indecently interfering with Cindy’s dead body. However, the latter charge was “no-billed” and abruptly withdrawn days before his 1990 trial largely on a technicality: medical experts could not pinpoint the exact moment of Cindy’s death.

In their submission calling for a resumed inquest, lawyers representing Cindy and Mona’s families slammed this as “repugnant”. The lawyers, from legal advocacy group National Justice Project, argued: “It is repugnant that Grant apparently escaped justice for indecently interfering with Cindy because of an assessment by the DPP that the evidence was insufficient to pinpoint her time of death. Grant was treated leniently from the outset given the circumstances – two dead children in his presence with his arm draped across the chest of Cindy’s near-naked body.’’

Grant was never charged with child abuse. June Smith maintains that had it been two white girls lying dead in the dirt alongside the uninjured Grant, “it would have been a different matter’’.

During Grant’s 1990 trial in Bourke, the Smith families were not told about the no-billing of the sexual interference charge, and a packed courtroom erupted with fury when the defendant was found not guilty of the remaining driving charges. His high-powered defence team, paid for by a wealthy, anonymous donor, had convinced an all-white jury that Mona, not Grant, was driving the ute when it crashed. (Grant initially told police he had been driving, before changing his story.)

Dawn Smith was “so shocked” by Grant’s acquittal she threw her shoe at the jury. Four years ago, when The Australian started to report on this cold case, Dawn Smith said she was so angry that if an armed policeman had been closer to her in court, “I would have grabbed his gun from the holster and shot that man (Grant)’’.

This week, the mother of eight who has lost three children, including Cindy, and continues to work for Bourke’s Aboriginal Legal Service, said: “You never get over losing any child’’.

Grant died in a NSW aged-care home around 2017, according to NSW Police. Despite this, George Newhouse, the National Justice Project CEO, said the decision to resume the inquest was “an incredible breakthrough’’.

Fiona Smith, Mona’s sister and Cindy’s cousin, said the inquest meant “a big weight has been lifted off our shoulders. It’s been the loneliest journey. It’s a good thing we’re all in the same town together because otherwise it would have been bloody horrible”.

Today, the girls’ remains are buried in a double grave at Bourke’s cemetery.

In the absence of anyone being held accountable for the cousins’ deaths, speculation has circulated in the outback town for decades: one rumour is that the girls were murdered; another is that several local Indigenous men were with Grant when the girls died on a remote stretch of highway.

The case was dormant until Richard Stanton wrote Enngonia Road, a forensic book on the case, published in 2017, which argued the police and prosecution cases were “fragmented”, “sloppy” and “badly managed”. Stanton, who did not speak to the lawyers or victims’ families, asked “why the police got it so wrong and how the accused walked away from the crash without a scratch and away from the court a free man’’.

Enngonia Road detailed how the fatal accident scene was not secured, while samples of dried material taken from Cindy’s left thigh were sent for examination but did not surface again. According to Stanton, Grant was not arrested after the crash, despite the fact he had been drinking heavily and two children lay dead in the morgue. Stanton also reported that Grant had previously been convicted of serious driving offences.

In a further investigative blunder, the defendant’s vehicle was released to a local business before it could be examined a second time by police. The day before a second officer arrived, the steering wheel was disconnected and shipped to Grant. The NJP has pointed out that the damaged vehicle – including the steering wheel – was never examined for fingerprints, despite Grant changing his story about who was driving when it crashed.

Grant’s barrister, Tony Quinlivan, told The Australian in 2018 that “justice was done” during the trial but also admitted: “Grant told barefaced lies.” The Australian interviewed the magistrate who committed Grant for trial, Rosemary Cater-Smith, and she condemned the police investigation as “incompetent” and urged that the case be re-examined.

Mr Newhouse said it had been “incredibly hard for us to obtain critical information relating to both the incident and the investigations that followed. … I can understand the frustration of families who’ve waited 35 years to get to the truth”.

An inquest into the girls’ deaths was started on November 8, 1988 but terminated the same day because Grant was committed to stand trial on the driving and interfere with corpse charges.

In 2018, the NJP asked NSW Attorney-General Mark Speakman to resume the inquest, but – in a significant blow – he rejected this request in March.

The NJP then adopted a new strategy. According to Mr Newhouse, “driven by the advice of Julie Buxton, a barrister from Melbourne, (we) developed a legal argument that the coroner had never completed the process of determining the manner and cause of the girls’ deaths after their inquest was terminated in November 1988”. The NJP argued that under NSW law, the inquest had to be completed.

On July 14, the NSW Coroner’s Court wrote to Mr Newhouse, stating inquests into the deaths of both girls would be resumed. The date and place of these inquiries have yet to be announced.

In another extraordinary legal twist, The Australian can reveal that in 2020, the NSW Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions rejected the NJP’s request to reassess the decision to no-bill the charge against Grant. A letter from the office, obtained by The Weekend Australian, said it “could not identify any error’’ in the 1990 decision. The ODPP called the failure to tell the grieving families the charge had been withdrawn “most unfortunate”.

Yet Ms Cater-Smith, accepted the evidence of witnesses, including police officers, that indicated Cindy’s body had been interfered with by Grant in a sexual way after she was found dead.

Mr Newhouse said The Australian’s reporting had been “critical to keeping attention on this tragic event, ensuring Mona and Cindy are not forgotten’’.

Fiona Smith said although revisiting the events surrounding her sister’s and cousin’s deaths “won’t be easy”, she saw the inquest breakthrough as “a blessing for us and for the girls, because it’s been a long time coming. Nobody deserves this sadness and this hurt”.