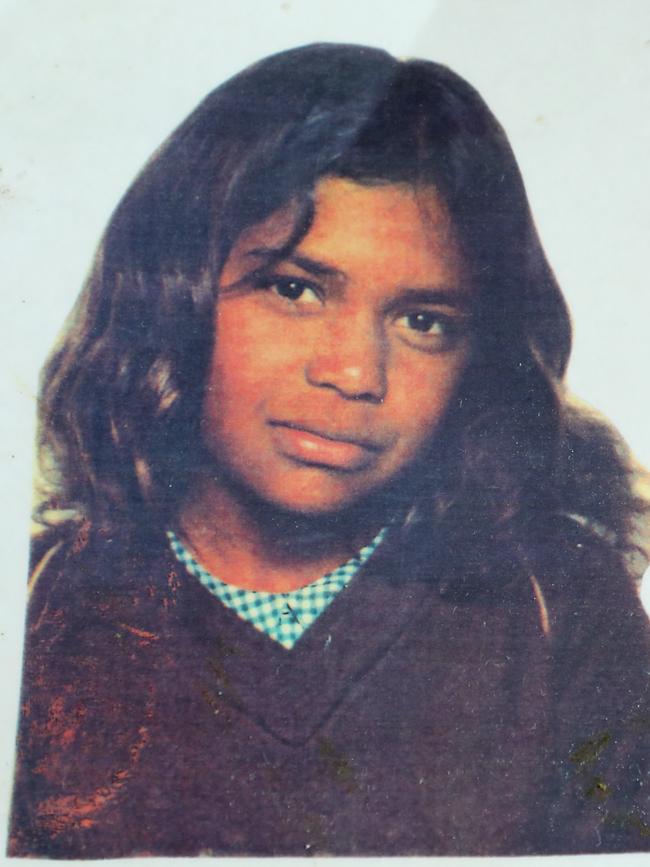

Mother Dawn Smith’s undying fight for justice over daughter Cindy’s death in Bourke road accident

Dawn Smith refuses to give up hope of justice for her daughter Cindy, 15, who was sexually molested as she lay dead or dying after an horrific road accident and her cousin Mona.

Bourke indigenous elder Dawn Smith refuses to give up hope of winning justice for “my little girl” — her daughter Cindy — 32 years after the 15-year-old was sexually molested as she lay dead or dying in a horrific road accident.

The 78-year-old’s hopes have suffered a cruel setback: she has learned the NSW Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions is standing by a highly controversial decision to drop a sexual offence charge against the middle-aged man who walked away unscathed from court — and from the car accident that killed Cindy and her 16-year-old cousin Mona outside Bourke in December 1987.

In a macabre twist, the man, Alexander Ian Grant, then 40, was found drunk and unharmed, with his arm slung across the exposed breasts of Cindy’s corpse at the accident site. While Mona, who had been partially scalped, lay in the dirt metres away, Cindy’s body was laid out on a tarpaulin and her clothing had been pushed up around her neck and down to her ankles.

The cousins had accepted a lift from Grant and never returned home.

Dawn, who works at the Bourke Aboriginal Legal Service, described the ODPP letter as “very disappointing. I still grieve. I still think about it (Cindy’s death). I think to myself what she would be like today if she was still with me.’’

In 1990, unbeknown to Cindy’s grieving family, a charge against Grant of “offer indignity to a dead human body” was dropped days before his District Court trial, and this was one of the reasons he avoided jail.

Decades later, the ODPP has argued that was the correct legal decision, though it has apologised for failing to inform Cindy’s family about the withdrawn charge on the eve of Grant’s trial.

The Australian has obtained a letter, dated November 12, 2019, in which the deputy director of NSW Public Prosecutions, Huw Baker SC, said: “I have not been able to identify any error in the ultimate decision that was made or this office’s consideration of the relevant legal issues.’’

Dropping the interfere with corpse charge was requested by Grant’s lawyers and largely rested on a technicality — medical experts could not pinpoint the exact time of Cindy’s death, therefore she may have been alive when Grant molested her.

Even though Cindy was a child and gravely injured, Grant was never charged with child abuse or sexual assault. Mr Baker argued the same issue — uncertainty about the exact time of Cindy’s death — would have “plagued a charge of indecent assault against Mr Grant’’. (He also argued that the fact that Grant was drunk could have militated against the interfere with corpse charge succeeding.) But Dawn Smith said: “If a blackfella had done it to white girls, he would have been locked up. There’s one rule for whitefellas and one rule for blackfellas … They were just two young girls.’’

The family’s lawyers, from legal advocacy group the National Justice Project, have urged the ODPP to “reassess’’ its response, which “does not assist our clients’’.

In a strongly worded letter, principal solicitor George Newhouse pointed out the two witnesses who first came across the fatal crash site found the near-naked body of Cindy lying next to Grant with her legs together. But the first detective to arrive on the scene later found Cindy’s legs had been repositioned — presumably by Grant — to expose her genitals.

“What was important was the evidence, accepted by the magistrate, that Cindy was dead when she was found by two independent witnesses, and that an alleged offence (moving her legs to expose her genitals) took place after that,’’ Mr Newhouse said.

Dawn, a stoic woman of few words, said her extended family — who are demanding an inquest into the girls’ deaths — would have seen justice by now if the girls had been white. In remarks that would resonate with the Black Lives Matter movement, she said: “If they had been white girls, it would have been a big issue. It would have been in the paper, there would have been big talk.’’

The acquittal of Grant at his District Court trial in Bourke before an all-white jury in 1990 attracted no publicity but caused uproar in the courtroom, with Dawn throwing her shoe at the jury.

Grant never faced trial over the corpse charge, and was acquitted on charges of culpable driving causing death after his high-powered legal team, paid for by an anonymous benefactor, successfully argued that Mona was driving when his ute crashed. Yet Grant had told a police officer he was driving when his ute crashed, before changing his story.

Despite this, the ute’s steering wheel was never examined for Mona’s fingerprints. Grant, an excavator driver, had the steering wheel removed from the wrecked car one day before police were due to conduct a second inspection of it — yet he never faced charges of perverting the course of justice.

Lawyers said police did not oppose bail for Grant or fingerprint the defendant, while samples of material taken from Cindy’s thigh at the accident scene were not produced at the committal hearing.

In a further blow for the families, NSW Police Commissioner Mick Fuller states in a letter, also obtained by The Australian, that police handling of the case was found by two independent inquiries to be “adequate”.

His letter, sent to NSW Attorney-General Mark Speakman on March 2 this year, notes Grant is now dead and that he does not believe an inquest into the girls’ deaths “will adduce new or additional information’’.

Yet the magistrate who committed Grant for trial, Rosemary Cater-Smith, has slammed the police handling of the case as “incompetent’’ and “all over the place’’, and has called for it to be re-examined.

NJP lawyers have described as “remarkable’’ the conclusion the police investigation was adequate.

The Australian has been told that when police officers met the girls’ family members and lawyers in Bourke for mediation meetings last year, police allegedly admitted the original investigation had been poor.

Mr Speakman had been considering an inquest into the long-neglected case, but said in a recent letter to the family’s lawyers that he was “currently minded not to direct that an inquest be held” partly because Grant, the only living witness for many years, was dead and because of the Police Commissioner’s advice.

Fiona Smith, Mona’s sister, said the official letters made her angry: “I didn’t like what I read in the letters. I don’t agree with it and neither does my Mum (June Smith, mother of Mona).

“It’s like they’re ducking and weaving and no one wants to take responsibility.

“My Mum loses her spark when things like this happen.’’

The family, which still lives in Bourke, had found hope in Mr Speakman’s earlier announcement he would consider an inquest, but Fiona Smith said when her mother found out about the latest official advice, “I saw her sink a bit more’’.

“It’s like nobody cares about the girls,’’ she said, adding that given the deep flaws in the investigation, authorities needed to give the girls and their families “some justice, something to walk away from this with.”