Indigenous voice to parliament threatens to muzzle families, says Clive Palmer

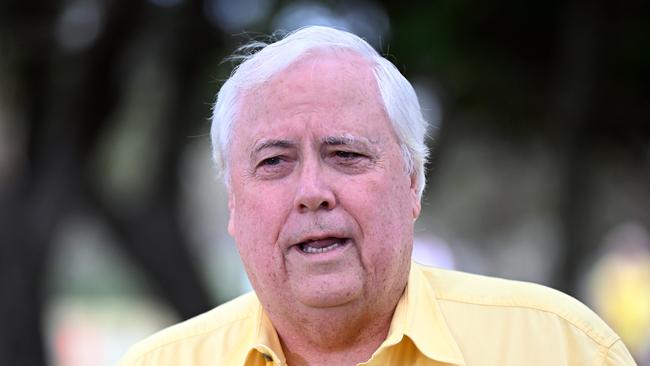

Billionaire mining magnate Clive Palmer is considering entering the referendum campaign for the No case against an Indigenous voice to parliament.

Billionaire mining magnate Clive Palmer is considering entering the referendum campaign for the No case against an Indigenous voice to parliament, arguing the advisory body will disempower Indigenous Australians at an individual and community level.

Mr Palmer, who spent $117m on his United Australia Party at the last election, said he planned to meet Indigenous Australians and federal MPs in coming weeks to determine whether he would actively campaign to sink the referendum.

He said the reason he opposed the voice was “different to what’s been put forward in other arguments” and warned the creation of a national Indigenous advisory body would “effectively muzzle the voice of hundreds of thousands of Indigenous families”.

While other No campaigners, including Peter Dutton, have warned the proposed constitutional amendment will hand the voice too much influence over government decision-making and policy development, heightening the risk of High Court challenges, Mr Palmer said the voice would make it harder for local problems in Indigenous communities to be addressed.

He said bureaucrats and local MPs would be tempted to defer complaints made by Indigenous Australians to the voice instead of responding directly to their concerns, and the advisory body would, in practice, become a barrier to government.

“This is another stunt to further persecute Indigenous people in this country and set up a difference of rights between racial groups to limit Indigenous people from bringing governments to account,” Mr Palmer said. “Indigenous people have got the same rights as any other Australian to question what their member of parliament does or what the government does. They shouldn’t be required to go through another hurdle to exercise their legitimate rights.

“At the present time, under the current Constitution, Indigenous people individually have the right to approach their members of parliament and the executive and make whatever submissions are in their interests or their family. If there was a committee to be established as envisioned by the voice, it would be too easy for government bureaucrats and politicians to say ‘take your complaint to the voice – to the committee’.

“Should people, because of the colour of their skin, have a barrier put up in terms of access to government? That’s the question that every Australian and Indigenous Australian has to ask themselves.”

While he opposed the voice, Mr Palmer said he supported constitutional recognition for Indigenous Australians, arguing this should be separated from the voice debate.

He also called on Anthony Albanese to respond to his concerns, urging the Prime Minister to provide more funding in the budget that could go towards improving conditions in Indigenous communities.

One of the leading figures behind the No campaign, Warren Mundine, said Mr Palmer had “probably highlighted something that hasn’t been spoken about”.

“Aboriginal people have a voice in several ways, through native title, through their land rights,” Mr Mundine said. “The other is that they are citizens of this country. No official or bureaucrat should be palming them off to another body. They have every right to confront and talk to their local members and the bureaucracy and go to Canberra and talk to them as they do now.

“During the era of ATSIC that’s exactly what happened. People were told go to ATSIC, have a conversation with them, rather than other Australians being able to talk to their elected member of parliament.”

Mr Mundine did not rule out meeting with Mr Palmer in coming weeks, saying he was happy to talk with people from the Yes campaign, the No campaign and those who were not part of either campaign.

“I will always have conversations with people. I’m a great believer in listening,” he said.

Mr Mundine said he was concerned the proposal in the final voice co-design report led by Marcia Langton and Tom Calma for a national voice to be supported by local and regional voices would create a new layer of bureaucracy that would end up “superimposing itself between the traditional owners on the ground and the government and the private sector”.

But Labor frontbencher Tanya Plibersek told Channel 7 on Monday that the referendum was “about acknowledging in our Constitution, the foundational document of our nation, that we don’t have a couple of hundred years of history, we’ve got 65,000 years of history and culture here in Australia”.

“The voice is about issues that affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. We know that we’ve got a big gap in life expectancy, in health outcomes, in remote housing, in employment, in education,” Ms Plibersek said.

“This is not about what politicians want. This is what First Nations Australians have been asking for and offering for decades now to be listened to on matters that impact on their lives.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout