Civil debate on Indigenous voice to parliament not beyond us

The Liberal Party’s calculation is disappointing but not surprising. Labor’s advocacy and processes have been appalling. Hopefully voters will rise above the crassness of the political class.

In an era of hyper-partisanship, when public debate has been dumbed down and polarised by social media, rancid identity politics infects every debate and our political class lacks titans of mainstream advocacy, we are going to hold a referendum about Indigenous affairs where the major parties will campaign vigorously for opposite sides. It is a feat as brave as the Burke and Wills expedition and could meet a similar fate.

BEST OF VOICE OPINION:All our commentators weigh in on the Indigenous voice to parliament

It would take more than Ben Lexcen’s winged keel to keep this debate upright. The great hope is that mainstream voters will rise above the crassness of the political class.

With any luck this country will demonstrate a capacity to deal sensibly with difficult debate, proving our systems and social cohesion are more robust than those in the US. After all, we held a plebiscite on gay marriage that proponents argued would be divisive and upsetting but that proved to be respectful and affirming.

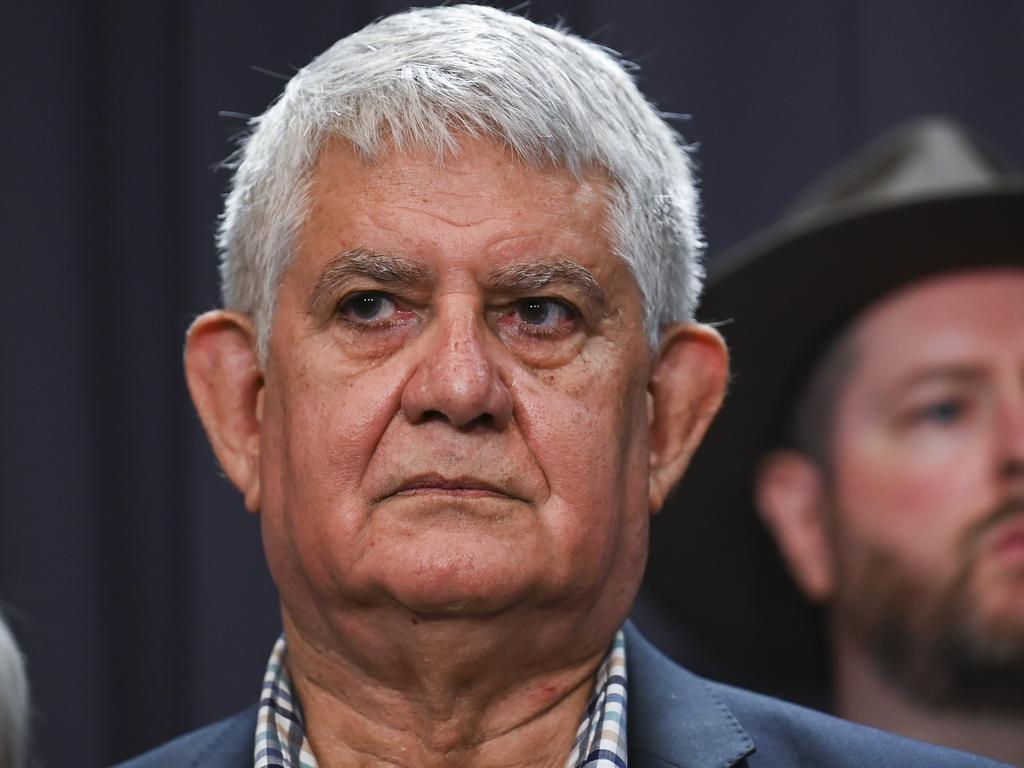

The voice referendum will be more difficult and it is already raising hackles. Voice opponents were quick to attack Noel Pearson for describing Peter Dutton as an “undertaker” looking to “bury Uluru”, and speaking of a “Judas” betrayal.

These complaints seem a little precious given the cut and thrust of political debate. Perhaps the complainants were envious of Pearson’s powerful imagery, using timely Easter metaphors to make pertinent points – surely this is not something we want to drive away from public discourse.

The truly reprehensible rhetoric came from Daniel Andrews. The Victorian Premier said it was “just wrong” to campaign against the constitutionally enshrined voice, that the Liberal Party was a “mean and nasty outfit”, and that leadership is about “calling out racism, bigotry and mean-spiritedness”.

This is a man who locked down his population and imposed curfews based on political considerations rather than medical advice – so hearing him describe others as mean-spirited takes the cake. Andrews’ response suggests he might not even have heard of Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, Warren Mundine, Anthony Dillon or any other Indigenous voice opponents – does he brand these people as racists for opposing the voice?

This does not augur well for a respectful debate in the months to come. Nor does the invocation of apartheid or race-based division by the voice opponents.

While the Liberal Party’s decision to join its Nationals Coalition partners in outright opposition has sharpened the partisan divide, the divisions within the voting public will be much more complex. We can expect many Liberal and Nationals voters to support the Yes case, as evidenced by some Liberal MPs already breaking ranks, not to mention former Indigenous Australians minister Ken Wyatt resigning from the party and Nationals MP Andrew Gee quitting too.

On the Labor side we are unlikely to see parliamentary defections, but many traditional ALP voters will oppose the voice. Even former federal environment minister and factional powerbroker Graham Richardson has declared his opposition – perhaps Andrews needs to declare Richo a bigot.

It is best not to categorise people and make moral judgments about them based on their party affiliation or referendum voting intention. Our default should be to assume good intentions for all (except Andrews, of course, who seems to be a charmless apparatchik who views everything as a test of ideological purity – even a virus).

As it happens, Easter Saturday is a perfect time to be contemplating the national project of reconciliation. At this moment, the voice model might appear to be wrapped in a shroud, behind a rock, awaiting a miracle.

Yet, for proponents, there is hope. Soon the political shadow boxing will be cast aside and we will focus on a straightforward debate about the proposal.

This demands a return to first principles, something sorely missing in recent months when the voice has been judged against ever-changing and politically convenient criteria. Will it end crime problems in Alice Springs? Will it improve the lives of children in remote communities? Will it end disagreement between Indigenous leaders? Or save money?

We also keep hearing the argument that a voice could simply be legislated, leaving constitutional recognition to a symbolic preamble. This is an annoying return to the debates of almost a decade ago, betraying how many politicians and commentators have paid scant attention.

Labor, seemingly, had zero interest in the voice discussion until it won consensus at Uluru in 2017. In fairness, that is when most of the country heard about the voice for the first time.

Advocates, including the Prime Minister, need to get back to the fundamental arguments for a voice, explaining its origins and intent. They cannot assume this knowledge.

Denouncing doubters and opponents, the way Andrews has, can be only counter-productive. Better to explain the imprimatur for this reform and assuage concerns about unintended constitutional consequences,

The cry for a voice reaches back almost a century to the earliest awakenings of Indigenous activism. Its modern incarnation, sculpted by Pearson, emerged almost a decade ago as a neat way to achieve constitutional recognition in a manner that would deliver meaningful, practical and permanent change.

It is about advancing reconciliation, atoning for the past by embracing future challenges together.

Given nations must be cohesive, and capable of striking out with unified purpose, Indigenous reconciliation is crucial for the nation’s future. So yes, the voice is about having a say, and yes, it is about putting up ideas and accepting responsibility, and yes, it is about closing the gap. But it is not proposed as the solution to any individual problem – it is bigger than that.

The voice, enshrined in the Constitution, is a plan to welcome permanently into our national arrangements the people ignored and discriminated against from the outset. It makes up for earlier misdeeds, not through guilt and blame but by providing a positive mechanism to improve the future – a mechanism that cannot easily be taken away.

Given our abysmal record on Indigenous disadvantage, the downside risks of the voice on social outcomes are negligible. At worst it could do nothing, at best it could be transformative; in reality, it is hard to imagine it will not deliver at least some better outcomes.

The risks to our system of governance need to be considered. But they have been grossly overstated in an orchestrated fear campaign by voice opponents.

The balance of parliamentary, executive and judicial authorities will be able to manage the scope of the voice – and if problems emerge, they can be corrected. Do not forget that we heard similarly shrill scares over Mabo, native title and the Wik decision. Where there are new laws, and new clauses in the Constitution, we can expect future activists and complainants to test them through the courts. This is why we have courts and three arms of government; it is nothing to be feared.

By any reasonable interpretation the current proposal neatly balances executive, parliamentary and judicial powers. The opinions of former chief justices of the High Court and other legal experts give us comfort.

The oft-repeated claims about this “inserting race” into our Constitution and “dividing the nation” are simply not true. Race is in the Constitution, has always been there, and this proposal does not hinge on race but indigeneity – it is recognition and a fair go for the descendants of the first inhabitants and has nothing to do with racial notions or characteristics.

The Liberal Party’s calculation is disappointing but not surprising. To be fair, Peter Dutton was in a difficult place. Whichever way he went he would face breakaways within his party, and he has been pushed relentlessly by conservative commentary agitating the base against this idea.

Yet he has pulled the wrong rein, allowing political positioning to trump the national project. The referendum could pass despite Coalition opposition, which would end Dutton’s political career, render the Coalition irrelevant for some time to come and ensure the nation will have weathered divisive antagonism on this issue for no good reason.

If the referendum fails, it could only be a narrow loss, and the Coalition would be blamed – as Wyatt and others have noted, it would be a historic repudiation on the road to reconciliation. In that sense, it is hard to see how the Coalition can fashion a win on this issue – its best hope was to engage, propose compromises and help shape a revised voice in return for bipartisanship.

Frustratingly, it has rolled over on much more problematic policies in recent years, such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme, Gonski education funding and net-zero emissions by 2050. But it is on the voice that it decided to take a stand and be intransigent.

We can expect more federal Liberals to dissent on this issue, while most state Liberals will argue Yes against the federal No. This will be ugly and divisive. And for what? To avoid the risk that some government decision, somewhere, might be challenged, sometime, by an Indigenous person wanting to be heard.

Liberal and Nationals MPs face a difficult brief. They need to argue that they support constitutional recognition and a legislated Indigenous voice – only they reject the version of recognition through a voice that Indigenous Australia has settled on, and claim a voice legislated under a constitutional clause will be unworkable.

Labor’s advocacy and processes have been appalling, which means the Coalition’s confusion is all their own work. Poor fellow my country.

On my 21st birthday this newspaper’s memorable front-page headline proudly proclaimed (above a picture of America’s Cup skipper John Bertrand punching the air in triumph): “Yes, we can do anything if we try!” But winning the old mug might prove a walk in the park compared with what this nation is about to try next.