Indigenous voice to parliament: ‘Out here’ in the APY Lands, early death the great divide

In the remote South Australian region, the odds are you’ll be dead before you’re 55. But despite this poverty of outcomes, or possibly because of it, there’s uncertainty about the referendum.

Out here, the houses are overflowing with kids and cousins. The cost of fuel and fresh food is eye-watering.

Teachers out here use a device called a Soundfield to amplify their voices so kids can hear through the gunk in their infected ears.

If you were born and raised out here in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands in the remote northwest corner of South Australia, the odds are you’ll be dead before you’re 55. A Torrens University study found that out here they have the highest rate of “premature mortality” in Australia. Out here is out of kilter with the rest of this healthy and wealthy country. Some argue the voice will divide us, but this nation is already divided.

The Anangu live in small communities on their traditional lands in the foothills of the spectacular Musgrave Ranges – it’s softly stunning, like an Albert Namatjira watercolour. Two thousand people are spread across an area the size of Germany 1200km from Adelaide, speaking either Pitjantjatjara or Yankunytjatjara. As a result of this extreme isolation, traditional culture is still deeply etched into the fabric of life. It’s pretty much a dry community, apart from occasions when grog is smuggled in. There’s a vibrant arts sector, the community is strong and there are some wonderful, committed whitefellas working with the Anangu to bring about change.

But on just about every social measure the folk of the APY Lands are the most disadvantaged people in Australia.

And so you’d reckon that out here they’d be clamouring for a voice in Canberra to address these myriad ailments. But despite this poverty of outcomes, or possibly because of it, there’s uncertainty about the referendum and an understandable distrust, an ingrained wariness, of anything that has the sniff of coming their way from whitefellas “over east”.

I first talked to the chair of Ernabella Arts, Anne Thompson, about the voice when I was visiting the APY lands in early September. She was deeply sceptical. “No one has really ever listened to Anangu in the past. Why now? What’s gunna change?”

She said she would need to be convinced about what the voice would do for her people before she’d vote yes. At that time she was leaning heavily towards no.

However, I spoke to Thompson again a few days ago when she was visiting Sydney for an exhibition and she is now more enthusiastic about voting yes. “I don’t think it’s gunna bring peace, but I am gunna vote yes, probably.” She says the voice will not fix all their problems, but First Nations people should be recognised. “We want to be respected.”

When I first spoke to the previous chair, famed artist Alison Milyika Carroll, she said she didn’t really know anything about the referendum and that “maybe” she would vote yes. A few days ago she told me people have been talking a lot about the voice. “Everybody is saying they are gunna say yes. Everyone in the arts centre and everyone in the community, they are all saying yes. People have been talking a lot. (A few) still (say) no, but most say yes.”

Old versus young

Rueben Burton, director of the Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Education Committee, has the same view as Anne Thompson, that whitefellas never listen. He says programs are foisted on the APY Lands from afar without any consultation, then the locals are blamed when those programs fail. But he reckons this is a chance for his mob to finally be heard.

Burton says the great challenge for his people is integrating the kids into the Western world – giving them opportunities for further education and good jobs – while maintaining a hold over traditional culture and language.

“My understanding about the voice … is to educate the government people to recognise the importance of Anangu (knowledge),” he says. “Maybe one day the voice can help us get the things that Anangu (need) … we want to say this is how we want to change things. We should be saying ‘This is how you do it’. I’m a supporter of the yes.”

Over the course of three days The Weekend Australian spent in the APY Lands we found both hard yes and hard no voters, but by far the vast majority were in the camp of “don’t know” or “haven’t decided”. Since then, however, there seems to have been a swing towards a yes vote.

There’s a split too, between old and young. The older people are generally more conservative, while the younger Anangu are more likely to be hankering for change.

‘Deeply suspicious’

Elder Donald Fraser, who as a young man was part of the campaign for land rights for his people, is critical of the way it has been explained. Back in the day, when he was part of the land rights push, he travelled around with lawyers and visited every single community.

They’d hold a meeting at night, explaining what land rights would mean to the Anangu, then there’d be a meeting the next morning, “The meeting in the morning was always the best meeting,” he says. “People would have gone away and discussed it amongst themselves around the campfire and they’d come back with questions.”

That hasn’t happened this time, he says. There’s confusion about what it will mean for Anangu. Politicians or government people will fly in, “talk to us for 10 minutes” and fly out again.

Fraser says while the Anangu have had rights to their land since 1981, it hasn’t brought them the great benefits he thought it would.

“As you can see, there are no jobs. We have been saying yes, yes, yes to people in the east, but we never get any services.” The voice could be a good thing but he is deeply suspicious. “I’m like a jackaroo sitting on a rail, wondering which way I’m gunna jump,” he says. When I spoke to him a few days ago he indicated he’d be jumping to the no side.

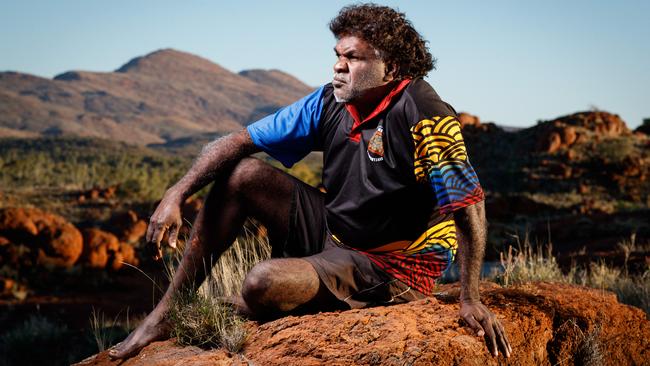

Phillip Marshall is an impressive young Anangu leader with big ambitions for his community.

Marshall, 32, was captain-coach of the Pukatja Magpies and a gun full forward. For the past six years he was elected to chair the Pukatja Council. He worked for years as a health worker in the Pukatja Clinic. He is highly respected in the community as an up and coming leader.

However, late last year, he moved his wife and their three kids to Adelaide so he could work in the emergency department at Royal Adelaide Hospital. He’s since moved to the Department of Human Services. He wants to get qualifications and as much varied experience as he can. “I want to see how things in the city work so I can take that knowledge back home.”

He also wants to give his three kids, aged 14, 12 and nine, opportunities that are simply not available on the APY Lands. “I want to lead by good example,” he says. “The community needs good leaders because a lot of people are struggling. I want to be an example to kids coming up.”

The voice, he believes, is a step in the right direction for the people of the APY Lands. “If we say no, we are still gunna be hangin’ around in the same place. If we say yes we are looking at something else, we are moving forward … Whether we say yes or no, we’re still dealing with idiots.” Better to steer those idiots in the right direction, he reckons, than the other way round.

For six years at the Pukatja Clinic Marshall was on the frontline, dealing with the immense health problems confronting the community. He’s seen a lot of death. There have been outbreaks of tuberculosis, scabies is common, and he was constantly dealing with middle-ear infections in many of the kids. “Lots of people in the community have diabetes, rheumatic heart disease, skin diseases … it comes from showers not working and houses that are not clean, and from too much sugar and not eating the right food.”

He says the root cause is poor education. He doesn’t believe his children will get the education they need to make it in both worlds if they stay on the Lands.

Education ‘disgust’

On that front, he has the backing of Peter Kenny, former principal of the Ernabella Anangu School, who was “disgusted with the state of education in the APY”.

Kenny had previously worked abroad for DFAT, UNICEF and UNESCO and in refugee camps in Syria and Jordan, where he says the quality of education – the delivery of services and the outcomes for students – was far superior. “I couldn’t believe there were places in my own country that were so deprived and were such an embarrassment and an indictment on the Education Department,” he says.

“Ninety per cent of the kids (for example) are affected by hearing impairment and that is a direct result of the racism (of the system).”

The on-the-ground services in areas such as health, education, child protection and policing are simply inadequate, and nowhere near the standard available to the rest of Australia. “The issues were not a shock to me at all. But the lack of services, infrastructure and lack of any strategic management by the government was just shocking.”

Kenny said he had to “fight like hell” just to put grass on the oval so the kids would have a safe place to play. “The oval was full of pebbles and bits of glass and junk, and when the kids did use it they’d cut their feet, and they already had lots of skin sores.” He had to mount what was basically a “covert operation” to get the turf up here and laid. “These kids deserve a safe playing field, just as all kids in Australia have.”

Kenny resigned at the end of last year after one frustrating year. “I couldn’t be complicit in what was happening and so now I am looking at other avenues to contribute or assist in creating a better education system.”

He says Phillip Marshall made the right decision, taking his kids to Adelaide to get them educated. “His kids aren’t going to get an (adequate) education there whilst we have no strategic management and we don’t attract the right people – nurses, teachers, doctors – and support them.”

Not ‘fair and equal’

There are many incredible and deeply committed people working on the Lands, but some services are fly-in, fly-out, says Kenny, which means there’s no continuity and no deep engagement with the community.

Kenny says the voice will not be a silver bullet to all these problems, but it will allow the Anangu to take back some control. “Someone like Phillip knows exactly what they need,” he says. “Why aren’t they the strongest voice in terms of governance?”

This lack of services was highlighted recently when there was a violent clash between feuding families and the police “were nowhere to be found”. Calls for help were diverted to Port Augusta, 1000km away.

“If police don’t start putting on proper services into these communities, then someone is going to get killed,” said Richard King, CEO of the APY Lands Council.

He said people in remote communities deserved to be able to pick up the phone to police when there is violence, and for the police to respond, as they would anywhere else in Australia. “This is what we mean when we say we want equal and fair treatment.”

Anangu are acutely aware of these problems in health, education, housing and policing. They’re just not certain a voice will make a difference.

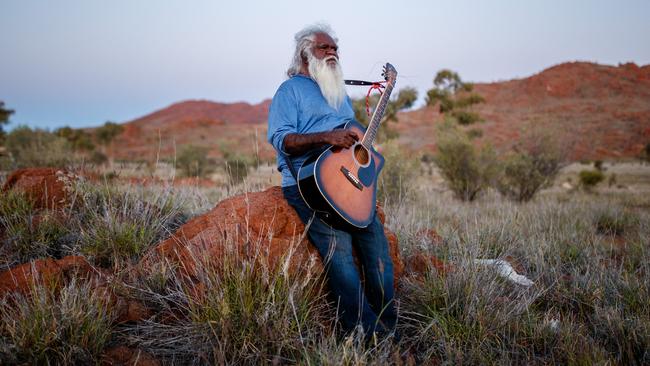

Trevor Adamson, a traditional owner and an old country music singer – he’s planning a trip “over east” in January to busk at the Tamworth Country Music Festival – says he’s just not sure about “this voice thing”.

“Our community here, it has a lot of problems,” he says, but not enough has been done to explain to his people how the voice will help solve these problems. “What are we saying yes to?” he asks. “We don’t know. I don’t really understand clearly. I don’t know if I’m gunna be able to vote yes to it. The Constitution, what does that mean to us?”

But then he says it would be good for someone from the APY Lands to be in Canberra to explain what their problems are. Will you vote yes or no? “I don’t know, I’m still a bit confused.”

Either way, the First Nations people of this country would seem to deserve at least what the rest of us take for granted – a good education, decent housing, responsive policing and a first-rate health system.

The issues are different out here, where you’re more than likely to be dead by the age of 55.

Many of the Anangu across the APY Lands have already voted. The people in this story will get their chance when the polling booth in Pukatja (Ernabella) opens on Tuesday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout