Former Prime Minister John Howard denounces Noel Pearson’s Indigenous voice to parliament 'Judas' attack on Peter Dutton

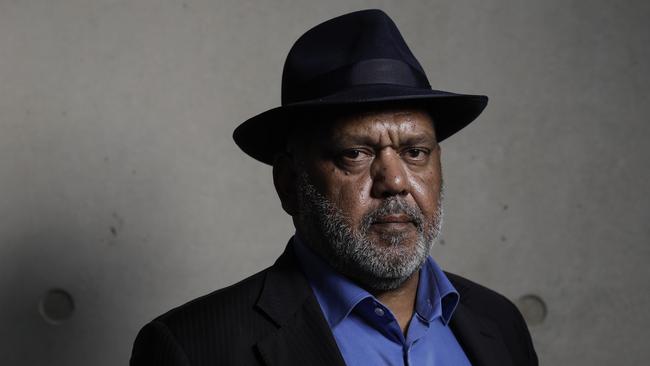

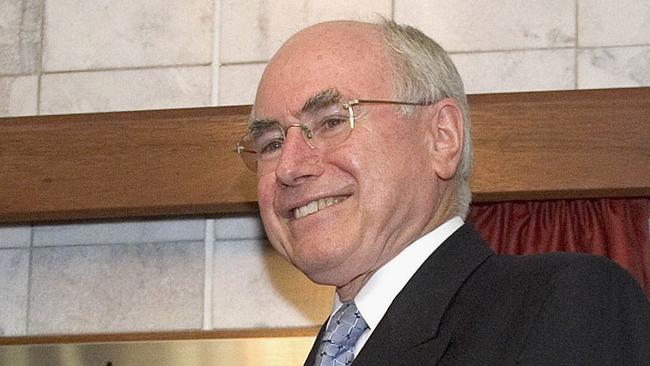

Former prime minister John Howard has denounced Indigenous leader Noel Pearson’s Indigenous voice to parliament attacks on Peter Dutton, believing the Opposition Leader has not betrayed the country or the Liberals.

Former Liberal prime minister John Howard has denounced Indigenous leader Noel Pearson’s attacks on Peter Dutton this week, describing them as “wrong”, “deceptive” and “very disappointing”, making it clear he believes the Opposition Leader has not betrayed the country or the Liberal Party.

Mr Howard spoke to The Weekend Australian after Mr Pearson on Thursday, in the lead-up to Easter, told ABC Radio National Breakfast: “I couldn’t sleep last night. I was troubled by dreams and the spectre of the Dutton Liberal Party’s Judas betrayal of our country.”

His comments came a day after Mr Dutton signalled that the Liberal Party had agreed to support constitutional recognition, and local and regional legislative bodies, but would not support the Albanese government’s proposed wording to amend the Constitution to create a constitutional Indigenous voice to parliament and executive government.

“I see what they’re doing today as a great betrayal because they are betraying their own policy and their own previous commitments,” Mr Pearson said on ABC radio, alluding to the commitments made by Liberals in power.

Mr Howard described Mr Pearson’s claim about a Judas betrayal by the Liberal Party as “terrible”. “It is a particularly offensive term at this time of year.”

“That sort of statement doesn’t do anything for the debate. That is profoundly offensive, quite, quite wrong, and demeaning of anybody who would use it,” he said.

“I am very disappointed he’s done that.”

BEST OF VOICE OPINION: All our commentators weigh in on the Indigenous voice to parliament

In his comments to the ABC, Mr Pearson said “when they go low, we’re going to go high. We’re going to meet fear with understanding”.

Mr Howard said he was disappointed about the quality of the debate, particularly the “moral intimidation” emanating from the Yes side. “The most objectionable thing to me is that there is an undertone, in some cases not an undertone but it’s an outright statement, from some people that if you don’t support the voice, you’re a racist.”

Late last year, Mr Pearson said “constitutional recognition is an agenda that was started by John Howard, let me repeat that again. Started by John Howard. It’s ended with a voice”.

Mr Howard accused Mr Pearson of conflating his calls, as prime minister, for recognition with a constitutionally entrenched voice. “He’s trying to conflate the two and say, well, there, the Liberal Party has always been in favour of the voice in principle because of what John Howard said in 2007.

“And that it is wrong because I was not calling for anything remotely resembling the voice. I was calling for some kind of preambular recognition.”

Mr Howard said while he could not speak for other Liberal leaders, his position has been clear. “For more than 20 years ago … what I had in mind was an acknowledgment of their prior occupancy. I mean, nobody can argue with that.”

As prime minister, Mr Howard laid out his commitment, if re-elected, in an address to the Sydney Institute on October 11, 2007.

“I would aim to introduce a bill that would include the Preamble Statement into parliament within the first 100 days of a new government. A future referendum question would stand alone. It would not be blurred or cluttered by other constitutional considerations. I would seek to enlist wide community support for a ‘yes’ vote. I would hope and aim to secure the sort of overwhelming vote achieved 40 years ago at the 1967 referendum.

“It rests on my unshakeable belief that what unites us as Australians is far greater than what divides us. Reconciliation can’t be a 51-49 project, or even a 70-30 project,” Mr Howard told the Sydney Institute audience at the Wentworth Hotel, five weeks before he lost his seat and the Liberal Party was swept from office.

Mr Howard revealed to The Weekend Australian this week that he had showed Mr Pearson a final copy of his address, or near final copy, before delivering it, “and he (Mr Pearson) was a little disappointed that I hadn’t gone far enough”.

“I have not had a one-on-one discussion with Noel Pearson since I ceased being prime minister,” he said.

Mr Howard said he had two concerns with a constitutionally entrenched voice: the role of the High Court, coupled with its impact on executive government because of its coercive power.

“I see adventurism by a future High Court,” he said.

“If the High Court of Australia can find, as it did in Love v the Commonwealth, that somebody born outside of Australia, somebody who’s not a resident of Australia, not a citizen of Australia, (who) is a citizen of another country, still can’t be deported because that person has Aboriginal heritage, then I think it can possibly find other things that people might not think are to be found in the Constitution.” The former prime minister said his other concern was the voice’s impact on executive government: “It will have a potential to clog up the process (of executive government).”

Mr Howard drew on Robert Menzies’ response to the Vernon Report in 1965:

“The Vernon Report recommended the establishment, by legislation, not by constitutional entrenchment, of an advisory body on economic policy. And it would be staffed and have all sorts of bells and whistles. It’d be a much, much bigger deal than the Productivity Commission. And Menzies rejected it out of hand because he said it would have a coercive effect on the government.

“Coercive is the word he used.

“Albanese was unconsciously channelling Menzies when he said at the Garma Festival that it would be a very game government that rejected a recommendation from the voice. Whereas Albanese is okay with that, Menzies wasn’t.

“And that (economic body) was a legislative body. If (the voice is) entrenched in the Constitution it is even harder. So, they’re the twin pillars of my concerns.”

Mr Howard also said claims that history supported the Liberal Party granting a conscious vote over the voice are wrong. “With great respect to those of my colleagues who say there should be a conscience vote – I mean, you can argue for a conscience vote – but it’s certainly not justified by Liberal tradition and Liberal history.

“Let me tell you about the conscience vote. Historically, the Liberal Party has had conscience votes on what you might loosely call moral issues. When I first came into parliament, within a year we had the Family Law Act, and that was a gigantic piece of social change. And that was a conscience vote.

“I had practised a bit of law and a bit of divorce work, and it was awful. We needed a huge change. I thought the concept of no-fault divorce was a good one. Those things like that and anything remotely touching abortion or stem cells, or RU486, there was a conscience vote.”

Mr Howard distinguished the conscience vote granted to all members of the parliamentary party, including cabinet members during the republic debate.

“Now, the reason why the republic’s quite different is that it was absolutely a foundation thing for our Constitution,” Mr Howard said. “The voice is important, but it’s not as important as whether or not we become a republic … (in 1999) it was just not realistic to have anything other than a free vote.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout