‘How will it change lives out here?’ Voice uncertainty runs deep in Moree, NSW

Moree’s Indigenous community once suffered some of the country’s harshest racial discrimination. Now its leaders are not all convinced the voice is the answer to present needs.

Moree’s first female Indigenous councillor is sitting in the town’s Aboriginal-run cafe wrestling with indecision over the voice to parliament.

“There are big voices in the Aboriginal community in Moree who are against it,’’ says Mekayla Cochrane, 27.

“The only thing swaying me towards a Yes is it might be the only chance in my lifetime that this happens. Do I want to miss that chance?’’

Across town, in a staff room at Moree’s dedicated Aboriginal medical service, Cathy Duncan is flicking through a glossy government information booklet on the voice.

As she reads each point, she throws up her own questions. “What does it mean for First Nations people in community,’’ she wonders, scanning the pages for more detail, anything that will help her reach a decision before October’s referendum.

Eventually she drops the pamphlet on the table and asks another question that echoes through this northwest NSW town: “How will it change lives out here?”

The local First Nations leader and chair of the Pius X Aboriginal health service calls in board member and long-time activist and elder Jacqueline Cain and asks what she thinks. “I’m a sovereignty person and I’ll be voting No,’’ Cain says firmly.

She reveals she’s already had No T-shirts made up with the words “it’s no shame to say no” and “sovereignty never ceded”.

“I’ll be wearing my T-shirt around Moree with pride,” she adds. “If they can’t pick someone from each community to represent that community on the voice then it’s not worth having.’’

Cathy’s daughter Jess Duncan pulls up a chair. She’s 27, a university student, a past dux of Moree Secondary College and a Pius X board member. She picks up on the “assumption from well-meaning, non-Indigenous people’’ that Aboriginal people automatically support the voice.

“I feel that there is a moralistic shame that is being attached to people who are voting No, particularly if they are First Nations,” Jess Duncan says. “I agree with Aunty Jacqui. I’m voting No,’’ she says. “We are sovereign peoples, sovereign nations with very diverse issues and yet this only involves a singular voice to parliament to advise. Nowhere does it say they are legally obliged to follow through.’’

The sentiment in this room – No and undecided – was reflected in other interviews conducted by The Australian during a visit to Moree in the last week of August, when uncertainty ran deep with many people saying they hadn’t yet fully turned their mind to the referendum.

It’s a position seized by the No camp with its “if you don‘t know, vote No” slogan. But it’s an opportunity identified by the Yes campaign to convert “the big mob in the middle, up to 30 per cent undecided” as Indigenous leader Noel Pearson put it. The people who want more information despite months of debate that has consumed the political class while leaving folk here in Kamilaroi country looking at their referendum booklets and government pamphlets with more questions than answers.

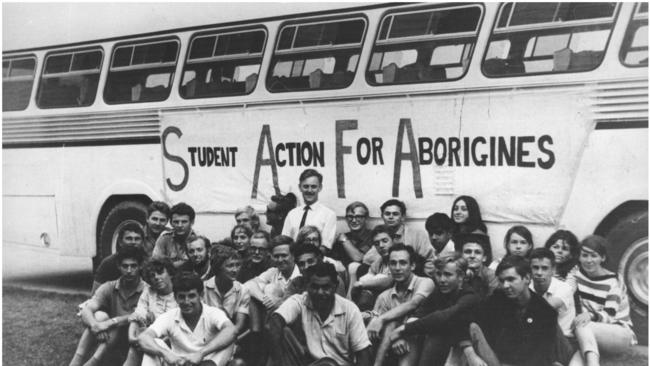

This is a small town with a big history. The legacy of enforced racial segregation exposed during the 1965 Freedom Ride is seamed into a community where the stains of inequality and bans on Aboriginal people visiting public places are readily called to mind.

Some still speak of undercurrents of racism, suspicious stares as they browse in shops, schoolyard slurs. Now the voice debate, Cochrane says, has unleashed shocking racism on social media.

About a quarter of Moree’s 7000 residents are Indigenous, according to the last census, and local figures speak of a strong and proud community working to provide Aboriginal-led services to tackle disadvantage, poor housing, youth crime and disengagement from education.

Cochrane was first elected to Moree Plains Shire Council when she was 24 and admits to feeling at times isolated as a young Aboriginal woman. There’s a big difference between listening and taking action, she says, and this feeds into her uncertainty over the voice.

“It will only be an advisory body – how many recommendations does a government have to have before they do anything?’’ she asks.

She pauses over lunch at the smart Aboriginal-run Cafe Gali. “There are communities, Moree being one, that already have very strong powerful voices of Aboriginal people who are quite confident and capable of speaking on their (community’s) behalf,” she says.

“Government could be investing in those voices, listening to them, instead of creating a body that would talk on behalf of communities. A lot of sway for the No vote comes from my community, and they have valid points. Not many in the community are Yes people that I know of.’’

The referendum, if passed, will recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Constitution through a voice that would give independent advice to parliament and government. Members would be selected by First Nations communities in each state and territory but the finer details on how it would operate would be decided by parliament after the vote.

At the SHAE Academy, an Aboriginal youth service focusing on sport, health, arts and education, chief executive Katie Smith is pondering the question of how the voice would close the gap. She too is uncertain which way she will vote.

“We’re working towards closing the gap every day, we don’t need the voice to do that. If you care enough about your community and your people, you don’t need the voice to do that. That’s the difference with small towns.

“I’ve got to look into it more, educate myself, because I don’t feel like there’s enough information that explains it. At the moment I lean towards No because we’ve got voices already in parliament. What are those voices doing? What will another voice achieve?’’

Cathy Duncan wonders if the referendum question should have concentrated on the single issue of constitutional recognition.

“Get that over the line and then have the next debate around the advisory committee, empowerment, self-determination, truth telling and treaty in a separate conversation,” she says. “I think they’ve mucked it up.’’

Links to history

Lloyd Munro grew up in Moree’s Mehi Crescent mission, one of 12 children to Lyall and Carmine Munro, heroic figures known for their years of sacrifice and activism.

“We grew up with our own mission primary school, we had our own pool because weren’t allowed to use the town pool,’’ Munro recalls. “We weren’t allowed off the mission. We had mission managers so we had our own community and our own church. That was our life until turning 12 and going to high school.’’

Munro was a small boy when Charles Perkins and fellow University of Sydney students rolled into town on the Freedom Bus, visiting the town pool that barred Aboriginal people and igniting a flashpoint credited with helping to shift public opinion towards a Yes vote in the 1967 referendum that allowed Aboriginal people to be counted in the census.

“Imagine what my dad went through and what my family went through in taking up the fight up for land rights and black power,’’ Munro says.

“When we moved off the Mehi over into whiter community … our house was targeted because of who we are and what my dad was trying to do. Our house was shot up. It was terrifying for us kids. But were always taught not to be disrespectful even though we were living in a time of many hatreds.’’

Now Munro, 62, is a community leader, on the boards of the land council, the Pius X Aboriginal Corporation, the Boomerangs Aboriginal rugby league club and the Miyay Birray youth service.

“Moree is the strongest community I know and powerful when we are one,” he says. “There’s a lot of good things going on here.”

Miyay Birray recently won more than $500,000 in state government funding for a new youth centre that will allow the group to expand. “It took over 30 years to get that funding,” Munro says. We’ve run on a shoestring, having to beg and borrow.’’

The Pius X Aboriginal medical centre is a linchpin for Moree and outlying areas, delivering everything from “mums and bubs” programs and a pre-school to mental health and suicide prevention, general practitioner and specialist services.

“We’ve got services, and those services work but we always need upgrades and funding and support so we can build on that,” Munro says. “There’s a lot more we need to do.’’

He is uncertain which way he will vote in October’s referendum.

“I know plenty of people saying no but I know others who are saying yes. If it’s a Yes, who is going to be that voice? That’s what everyone is asking. How is it structured?

“If it’s a No where does that take us? Are we going to spend another 100 years trying to get support and help where it’s needed the most?’’

The town has its problems. Figures from the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research show the Moree Plains shire has among the highest rates of domestic violence and assault, robberies, break and enters and motor vehicle theft in the state, with Aboriginal people over-represented in some categories as victims and perpetrators. They are issues the community is trying to work on, says Smith, airing her frustration over the time spent trying to secure funding through state and commonwealth bodies.

Her group has runs on the board, she says, offering up the example of the academy’s success in assisting about 20 young men gain TAFE construction qualifications. “The majority of them have gone into full time work and about half of those men were young dads with small families,” she says.

Cochrane wants to see facilities and conditions improved in South Moree where she says most First Nations people live. She suggests driving north to south down one of the streets to understand the divide. “You will see the difference once you cross bridge,” she says.

The burnt-out houses and abandoned cars around that southern part of town are indicative of problems many want fixed.

Brighter future

In Moree’s main street, Cafe Gali is doing a steady trade as bright new Aboriginal paintings are unrolled at the adjoining Yaama Ganu Gallery. Both enterprises are operated by the Aboriginal Employment Strategy, a not-for-profit program launched in Moree by cotton farmer Dick Estens in 1997. It has since expanded nationally and secured more than 20,000 jobs and 2500 traineeships.

Five Indigenous staff are employed at the cafe, including manager Mel Hammond, 44. She loves her job and says things are changing around Moree. She sees more Indigenous people working in the town and believes “a lot of people are working to make things better’’.

Hammond hasn’t heard a lot about the voice but says in the lead-up to the referendum she would seek out more information to help her come to a decision. The Australian Electoral Commission pamphlets arrived at most people’s homes this very week.

“People don’t really talk about it much. I think a lot of people probably haven’t made up their minds,’’ Hammond says.

The very question has put a cultural load on First Nations people, Cathy Duncan says, an expectation that they should know the answers.

“I have friends who challenge me, non-Indigenous people who want us to answer their questions,” she says. “People ask me which way to go and I say, choose your own path.’’

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout