Anthony Albanese’s Indigenous voice to parliament is a gamble for the nation

Anthony Albanese ignored the wise steps needed for a successful referendum. Now Australia is heading towards a dangerous political showdown on October 14.

Anthony Albanese has broken every rule in the book on how to prevail in a referendum. The Prime Minister has done so with much cheerleading from the political class, media and corporates. Given that since Federation Labor has put 25 referendums for 24 defeats it is extraordinary that Albanese was not more astute than to dismiss virtually every prudent step necessary for success.

We are finishing in a bad place. The contrast with the unity surrounding the 1967 referendum could hardly be greater. Yet we have had truckloads of time. It is 16 years since Liberal prime minister John Howard pledged constitutional recognition of the Indigenous peoples at the 2007 election.

The divisions today are greater than ever on a question of supreme consequence. The voice is marked by legal and political uncertainties and partisan dispute with history suggesting these are harbingers of a referendum defeat. The project, inspired by goodwill, has been mismanaged; the fear is it finishes in a train wreck next month.

There is distinct on-the-ground resentment at the corporate, finance, celebrity, educational, professional and sporting forces – an alliance of elites – talking down to people, patronising them, signalling the voice as the morally superior choice for the nation. If the voice is defeated, this campaign by the elites will rank as one of the worst political own goals in Australian history.

Consider the two scenarios.

If the referendum is carried it will be a razor-thin margin. The divisions will remain. At that point the real task begins – constructing the voice in terms of its functions, composition and procedures, a daunting job. It means building, from the ground up, an exclusive Indigenous political institution, created to represent one group of Australians, yet required to win legitimacy within the operations of government and parliament and acceptance by the wider public. The challenge for our politics and national life will be immense.

Indigenous leaders and the Albanese government will feel vindicated in victory – a victory riven by disunity. Yet the ongoing dispute over core principles will be an ominous circumstance for the voice’s creation.

Any referendum defeat, on the other hand, runs the grave risk that the wrong conclusion will be drawn, namely that the public has withdrawn its goodwill, rejected recognition and Indigenous aspirations, as distinct from rejecting a contentious model. The danger is the Yes camp, having misjudged the referendum, might then misjudge why it was defeated. If the voice goes down, the Yes camp must reflect upon itself, not the voters.

If the voice is rejected, that will be driven by two overwhelming factors: the defects in the constitutional proposal and the uninterest in pursuing bipartisanship. These problem were obvious from the time Albanese spoke at Garma in July last year, yet they have been subject to denial for 14 months by the Yes campaign and its supporters.

There were many different versions of the voice on offer, virtually all less radical than the chosen model. Father Frank Brennan pointed out 18 versions of the voice were put to the 2018 parliamentary committee. It was always possible to legislate the voice first, a sensible approach that would have transformed the atmospherics by putting the constitutional question at the end, not at the beginning. That was vetoed.

The parliamentary committee concluded the model for the voice was not settled and “more work needs to be undertaken to build consensus on the principles, purpose and the text of any constitutional amendments”.

Bipartisanship was seen as essential – but that view was ditched.

Brennan said for the past five years, “both sides of politics seem to have given up on bipartisan co-operation”. More recently, he warned Albanese, tried to get the proposal modified, and was scorned.

‘The fundamental changes it embodies to the principles of Australian democracy will last forever.’

After Albanese became Prime Minister and decided to press ahead he saw no need for a wider forum or a convention to bring together Indigenous, non-Indigenous and cross-party MPs. He believed the voice could be carried on Labor support, elite funding and a more progressive country than voted in same-sex marriage. That judgment is on trial next month.

Such confidence underwrote the critical decision – the model for next month’s vote. It involves the creation of a new chapter of the Australian Constitution, so the voice sits adjacent to the parliament, the executive government and the judiciary as the fourth arm of our system. Constitutional recognition of the Indigenous peoples “as the First Peoples of Australia” is achieved through the voice, thus fusing the two concepts. It is a group-rights political body designed to pursue the interests of one section of the Australian nation, defined by ancestry, yet empowered to make representations to the parliament and any element of executive government about proposed laws and policies of Indigenous interest and of the general interest. It will exist in perpetuity. The fundamental changes it embodies to the principles of Australian democracy will last forever.

Contrary to the repeated claims of the Yes supporters, this model is neither modest nor simple. It is filled with complexity and unknowns. There are myriad grounds for objections in terms of principle and practicality. All aspects of the voice’s appointment and operations will be decided by parliament. That’s essential. It means, however, much remains unknown, thereby giving the No camp an automatic pitch: “If you don’t know, vote No.” Surely the government should have rolled out a fuller picture of the voice.

Let’s be honest. A referendum of such import needed to be bipartisan. Former chief justice Robert French said the voice was “a significant institution in our representative democracy”. The late and great barrister David Jackson said of the voice that it meant “we become a nation where, whenever we or our ancestors first came to this country, we are not all equal”. Such a change to Australia’s governing principles and social compact – in the cause of Indigenous recognition – should not have been put without significant cross-party support.

This means if bipartisanship was not available then the referendum should not have been proposed in this form. There were other models and approaches available.

We know why this didn’t happen. The Indigenous leadership, influenced by Noel Pearson, insisted on the current model. Indeed, they would accept none other, a calculated and understandable judgment. Indigenous leaders, battle-hardened after decades, saw their chance and went for the big, bold, breakthrough. They bet the house.

Pearson, it seems, hoped Howard would climb aboard. But it was never going to happen. Albanese signed on the dotted line.

Albanese walked, eyes open, into the trap. He put the preferred Indigenous leaders’ model. He didn’t negotiate them down as Paul Keating did with native title. That meant Albanese was locked into a model the Coalition under Peter Dutton was never likely to accept and was always going to struggle. If Albanese had made concessions to the Coalition he would have lost the Indigenous leaders and he couldn’t propose a model that didn’t have their consent.

This was not just Albanese’s dilemma. It is Australia’s dilemma on the issue of recognition. It will remain the dilemma after any defeat of the voice. Contrary to what is being said now, the debate about recognition won’t fade away. It will merely take another turn. But any recognition proposal needs Indigenous authorisation. This raises the existential question for the future: can agreement be found between majority public sentiment and Indigenous sentiment?

Unsurprisingly, Marcia Langton said this week that if the voice was defeated she would not work with Dutton on a second, different referendum to achieve recognition.

Indigenous leaders are focused on the big prize. Hence, the “all or nothing” mentality surrounding the October vote. Langton has called on the Albanese government to sketch an alternative future if the voice does down.

Appearing this week at The Australian’s voice debate in Sydney, Pearson provided the most effective reframed case for the voice so far. Shifting the rhetoric, Pearson returned to the central proposition he has argued for decades – the future of the First Australians is about locking rights and responsibilities together. This is his vision for the voice.

Going to the principal task, he said: “Unless we take responsibility, they’ll be no turnaround in closing the gap.” This is how Pearson sold the voice. Frankly, it should have been the overarching message from day one but probably arrives too late in the day.

The trend favours the No camp but the contest remains open. This week Newspoll showed No in front 53-38 per cent, with 76 per cent of Coalition voters saying No. Every age group from 35-49 and upwards was voting No. The vote in the regions was 61-31 against the voice.

The Essential poll published in Guardian Australia showed a tighter contest with No leading 48-42 per cent. It showed the hard No vote leading the hard Yes vote 41-30 per cent. It had young and female voters still in play.

The issue for the Yes campaign is how far it changes tactics to reverse the trend. The John Farnham promotion reveals the sustained effort from the Yes side to recast the voice as an agent of goodwill and positivity.

Pivotal to the struggling position of the voice is the Coalition’s opposition to enshrining the voice in the Constitution. This is not new. It was opposed by Tony Abbott, rejected by the Turnbull cabinet and opposed by Scott Morrison as prime minister. This position has been known for years. That Albanese felt it unnecessary to address this obstacle was extraordinary.

The government seemed to assume the Opposition Leader could be intimidated into ditching an established Coalition stance, betraying Coalition voters and rolling over to Labor’s position. Albanese didn’t create a process that would force Dutton to negotiate.

Options to proceed could have included a constitutional convention, a more limited voice model or a legislated pathway. The Indigenous leaders insisted on their model. But Albanese has the power of the prime ministership – there is only one conclusion: the voice being put is the model that Albanese wanted.

Any defeat of the voice, therefore, will reflect serious misjudgments by Albanese. His launch of the voice campaign in his Garma speech in July last year now reads like a trip in an unreality bubble.

In this speech – conspicuous for its elegance – Albanese pledged to implement the Uluru Statement from the Heart “in full”. He said “the country is ready for this reform”. He declared “the tide is running our way” and “the momentum is with us, as never before”.

Albanese felt the country was on a roll – “as never before” – the implication being Australia’s heart would open to the project.

He branded the proposed change as “momentous” but also “simple”. Even at the time the contradictions were obvious. Albanese said the voice was nothing more than “simple courtesy” – yet it was a body that would have “the power and the platform to tell the government and the parliament the truth about what is working and what is not”. That’s power. Indeed, he said enshrining the voice in the Constitution meant it “cannot be silenced”. That’s power.

But at the same time it was just a “courtesy”, nothing more than an expression of respect.

The point, of course, is that this referendum was always about representative power.

Albanese’s claims became too delusional to ultimately assist the government or the Yes case. It is extraordinary, however, the extent to which influential figures accepted this mantra at face value, repeated it, tried to claim “nothing to see here” and then became indignant and resentful when the No case highlighted its multiple problems and contradictions.

Albanese invoked the voice, the role of Makarrata, treaty-making and truth-telling. Conspicuously, he was in a hurry.

He rolled out three suggested sentences for the constitutional change along with the proposed question to be put to the people. He wanted the question settled “as soon as possible”.

As Brennan said, Pearson was instrumental not only in proposing the voice but in removing all other options from the table. Labor endorsed this big-stakes play. Pearson had always seen a voice as a conservative concept, only advisory, and hoped to win a significant slice of Coalition support. But he misjudged.

In his appearance at The Australian’s forum Pearson came to grips with the ultimate dilemma raised by the voice: it infringes the principle of classic “equal before the law” liberalism, now the central idea in our polity (though it long excluded the Aboriginal people).

On the other hand, recognising the Indigenous peoples as the First Australians must demand a new category of special or separate Indigenous rights and the task then becomes the need to fit these idea together.

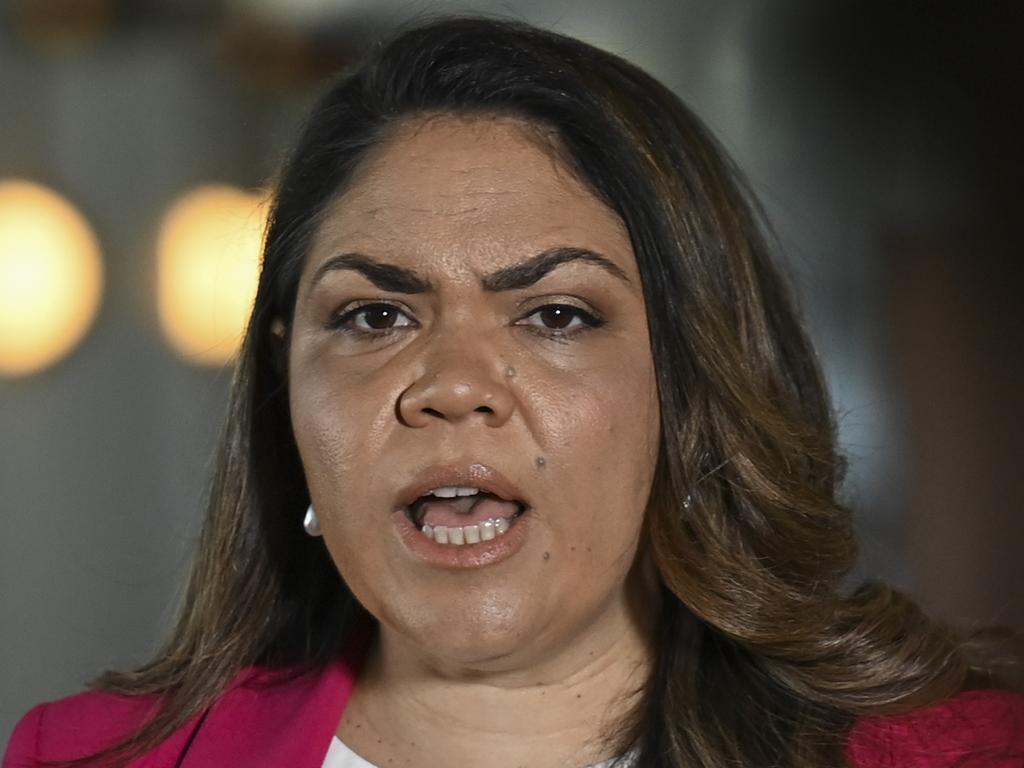

Pivotal to the voice debate is the role of Indigenous leaders – senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and Nyunggai Warren Mundine – spearheading the No case.

This shows that Indigenous Australians don’t speak with one voice and don’t have one view. The fact Price, an avowed opponent of the voice, was sitting in the Nationals partyroom at the time of this debate became decisive.

Price has waged a relentless campaign, appealing to the deepest instinct in the Australian psyche.

“We are being divided,” Price told the parliament. “We will be further divided throughout this campaign. And, if the vote is successful, we will be divided forever. I want to see Australia move forward as one, not two divided; that’s why I will be voting No.”

Price has made the critical pitch: saying the voice is about separation, that it will divide rather than unite the country.

If the public instinctively accepts this view, the voice will be voted down comprehensively; the states won’t matter, the national majority will sink the referendum. The No case essentially argues Australians accept constitutional recognition but oppose the voice.

There is a further elemental force at work: every element of power is loaded against the No case. The actual question is loaded. Whether it is financial clout, celebrity endorsement and institutional backing, the Yes side holds a commanding position. One side is advantaged against the other.

The risk for the Yes side is this backfires: that more Australians will kick back and assert their independence.

Since World War II there have been five successful referendums. Each referendum was successful across the entire nation, carried in all six states. The national vote varied from 54 per cent to 91 per cent. But in four of these five successful referendums the lowest national vote was 73 per cent in favour.

The lessons – if you win, you win big; and you don’t win in a divided polity.

Australia is heading towards a dangerous political showdown on October 14 – the referendum on the voice should never have been advanced in this manner, devoid of formal political bipartisanship and with a conga line of elites lecturing ordinary people on a scale unmatched since World War II.