Anthony Albanese’s Indigenous voice: simple yes or no

Anthony Albanese will put a ‘simple’ yes-or-no question to a referendum to create an Indigenous voice in the Constitution but with politicians retaining the power to define its functions.

Anthony Albanese will put a “simple” yes-or-no question to a referendum to create an Indigenous voice in the Constitution to make recommendations on Aboriginal issues to parliament but with politicians retaining the power to define its functions.

At the Garma Festival on Saturday, the Prime Minister will for the first time outline how the Constitution should be changed to accommodate a voice – a key part of the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart – amid a debate over whether the final design of the body should be unveiled before a referendum.

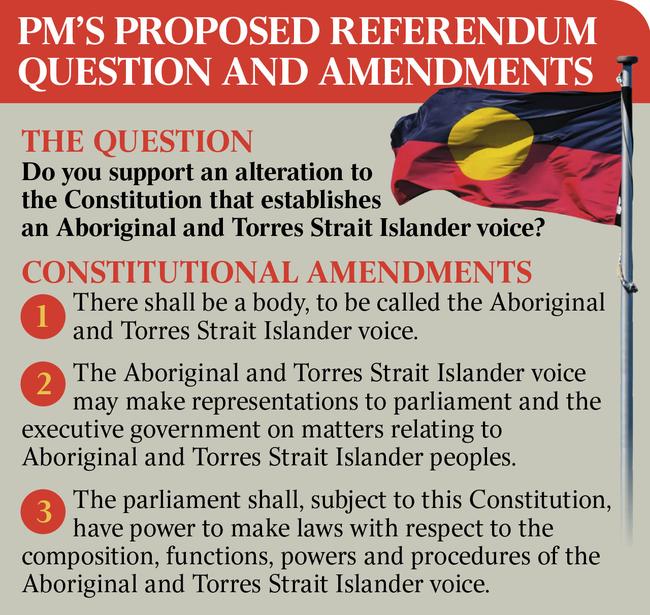

Mr Albanese will also suggest the wording of a referendum question to be put to the public, calling the draft proposal the “next step in the discussion about constitutional change”.

“We should consider asking our fellow Australians something as simple as: Do you support an alteration to the Constitution that establishes an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice?” Mr Albanese will say.

“A straightforward proposition. A simple principle.

“A question from the heart. We can use this question – and the provisions – as the basis for further consultation.

“Not as a final decision but as the basis for dialogue, something to give the conversation shape and direction. I ask all Australians of goodwill to engage on this.”

Seeking a middle path in the voice debate, the Prime Minister will argue Australia “does not have to choose between improving people’s lives and amending the Constitution. We can do both – and we have to”.

The reform would put an end to “121 years of commonwealth governments arrogantly believing they know enough to impose their own solutions on Aboriginal people”.

Mr Albanese will say the government’s “starting point” recommendations on how the Constitution would be changed include three new sentences that would guarantee the existence of the body, give it the power to “make representations” to government on behalf of Indigenous Australians, and give parliament the power to decide how the voice will function.

“There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice,” is the first of the three sentences Mr Albanese recommends to be put in the Constitution if a referendum is successful.

“The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice may make representations to parliament and the executive government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

“The parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to the composition, functions, powers and procedures of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice.”

The Prime Minister will say the draft provisions “may not be the final form of words, but I think it is how we can get to a final form of words”.

Mr Albanese this week confirmed a referendum on a constitutionally enshrined voice would be held in this term of parliament as part of the government’s vow to implement the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart in full.

This was echoed by Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney, who had previously warned the government would not propose a referendum on the voice unless she was convinced the yes vote would prevail.

Mr Albanese’s move to outline draft constitutional amendments and a referendum question comes amid a split among Indigenous leaders over whether the final form of the voice body should be outlined before the proposition is put to a public vote.

Coalition of Peaks convener Pat Turner and Indigenous Coalition MPs have demanded detail on how the voice will work before it is put to a public vote, while Noel Pearson and Megan Davis are among Indigenous leaders pushing for the referendum to come ahead of the detailed design of the body.

Mr Albanese’s draft suggestions make clear the design of the body would be a matter for the parliament but the voice mandate would not exceed acting as an advisory body to the federal government on issues that impact Indigenous people.

On Saturday in Arnhem Land, Mr Albanese will say the creation of a voice would assist in improving the standard of living for Indigenous Australians, warning the campaign could be derailed by voter “indifference” if it was viewed as a symbolic gesture.

“There may well be misinformation and fear campaigns to counter. But perhaps the greatest threat to the cause is indifference. The notion that this is a nice piece of symbolism but it will have no practical benefit,” he will say.

“Or that somehow advocating for a voice comes at the expense of expanding economic opportunity, or improving community safety, or lifting education standards or helping people get the healthcare they deserve or find the housing they need.”

He will describe the “torment of powerlessness” as creating a life expectancy gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians of 20 years, as well as high rates of incarceration and disease for First Nations people.

“And if governments simply continue to insist they know better then things will get worse,” the Prime Minister will say.

He will urge the Coalition to offer bipartisan support to the yes case for the referendum, with opposition Indigenous Australians spokesman Julian Leeser attending the Garma Festival.

At Garma on Friday, West Australian senator Patrick Dodson said the voice referendum would be a sign of Australia’s maturity after the 1967 referendum that gave the commonwealth powers to make laws for Indigenous Australians.

Senator Dodson, the government’s special envoy for reconciliation, said the referendum 55 years ago was overwhelmingly successful because Australians realised how Aboriginal people lived under awful public policy of the states. “It was the first time that people living in humpies was exposed on television, where the welfare people were taking kids off their mothers because they were deemed not capable of looking after them,” he said.

“I think Australians were very moved by that. There was a big revelation that things weren’t right in this country and we need to fix it.

“Here we have the legacy. Having had High Court judgments in Wik and Mabo, the royal commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody, the Bringing Them Home report, we’ve been informed fairly well over the last 10 to 15, maybe 20 years about the state of our relationships between each other as First Nations peoples and as settlers.”

Senator Dodson said the voice referendum was “an opportunity for us to go forward together in a positive way”.

“(It) signals to the world, a sense of our maturity as a nation dealing with our First Nations by actually putting an onus in our Constitution for them to have a voice because in the past, that was at the whim and fancy of a government,” he said.

“This is for the stayers. You’ve got to be a stayer in Aboriginal affairs if you want to get outcomes. It’s taken us nearly 200 years to get to the question of whether we might have a legal onus in the Constitution that gives rise to a voice to the parliament for the people that we’ve conquered.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout