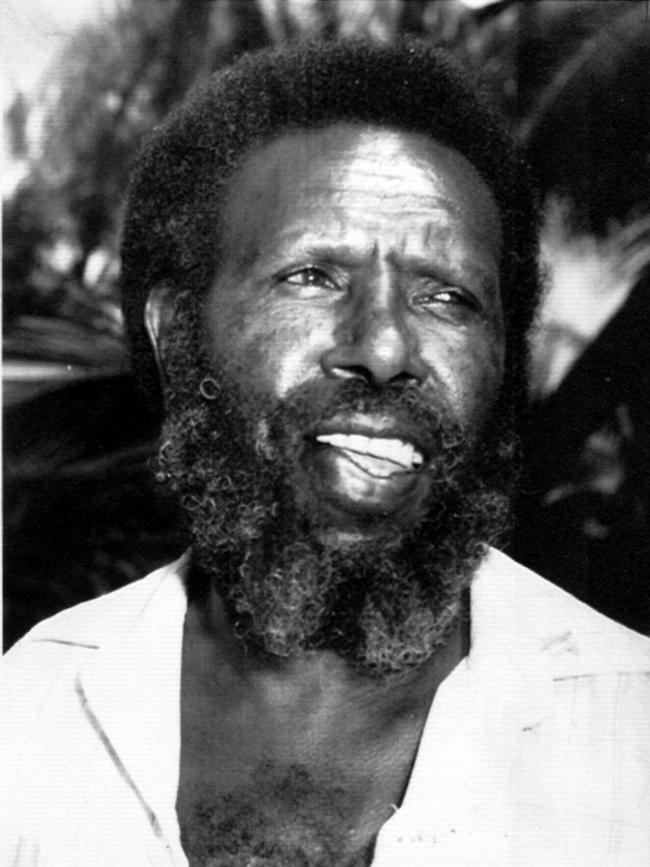

Mabo granddaughter doing her bit to close the health gap

Rebecca Mabo, granddaughter of land rights campaigner Eddie Mabo, is helping close the gap in healthcare.

Crippling shortages of doctors and nurses in remote communities mean Australia’s health system has a long way to go in closing the gap – but many frontline First Nations professionals are fighting to improve outcomes and pave the way for medical reconciliation.

One of them is Rebecca Mabo, granddaughter of Aboriginal land rights campaigner Eddie Mabo, who now works as a nurse and midwife at Mount Isa Base Hospital. The Meriam, Manbarra, Dunghutti and South Sea Island woman was the first Indigenous student to graduate from her course, a bachelor of nursing and midwifery at Victoria’s Monash University, and hopes to help other First Nations communities overcome the lingering distrust that exists towards hospitals and healthcare settings.

“As a proud First Nations woman I have always felt a sense of duty to my people, and even more so knowing that I stand on the shoulders of giants. Not only my grandfather, but my grandmother, Bonita Mabo, and all the incredible strong people that came before me,” Ms Mabo said.

“I am only one person in a massive healthcare system, so I understand that I may only have an effect on a micro level, but even then I still feel like that makes a difference.

“I also think being visible within the hospital, healthcare services and community and being a positive role model (will help).”

By 2031, national targets aim to see First Nations people represent 3.43 per cent of the health workforce. A little over four years after the Closing the Gap initiative was launched, Queensland’s North West Hospital and Health Services (NWHHS) has not only exceeded, but tripled, that national target.

The NWHHS employs 17 nurses who identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, with nine of those, including Ms Mabo, in leadership positions – making up 10 per cent of their workforce.

Ms Mabo believes mentorship and improving pathways into tertiary studies are two big challenges that need to be addressed to improve the participation of Indigenous medical students.

“I was fortunate to have some really beautiful mentors while studying, both First Nations midwives and staunch allies, who really supported me,” she said.

“Investment in community-led initiatives that are developed by First Nations people for First Nations consumers (is needed).

“Shifting a focus away from specific targets to focusing on a more holistic, well-rounded view of health and wellbeing. I feel like we are still laying the groundwork at this stage, and change is slow, but there are a lot of positive things happening in the area of healthcare.”

With an expected shortfall of 70,000 nurses in Australia, including a gap of 9000 Indigenous nurses by 2035, NWHHS First Nations health executive director Christine Mann said having a strong workforce was a “powerful driver of change” for Australia’s healthcare system.

Over the past 18 months, an extra 24 full-time positions – spanning nursing, allied health and Aboriginal health practitioner roles – have been created in the First Nations portfolio.

The additional annual investment of $5.2m aims to benefit the health outcomes of First Nations patients and help close the gap when it comes to disease.

Ms Mann said by having a “strong and well-represented” workforce, the healthcare system could then improve accessibility, ensure culturally safe care and improve patient experience for First Nations people.

NWHHS attributed its achievements to providing more opportunities and better accessibility for those interested in pursuing a career in healthcare.

“Over the last two years, we’ve been implementing a suite of programs ranging from school work experience through to tertiary cadetship programs,” Ms Mann.

“School work experience seems to be pipeline into school-based traineeships where students are gaining a certificate II and III over a 12-month period.

“Partnerships have been key in this space, particularly with some of the large hospital and health services.

“A key to success is when you have a workforce familiar with community. There’s an embedding in the health system, ways of knowing and doing in practice.

“We’ve got people in the health service who are able to link cultural considerations to clinical care and that can be quite a significant difference between getting someone on board on their health plan or not.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout