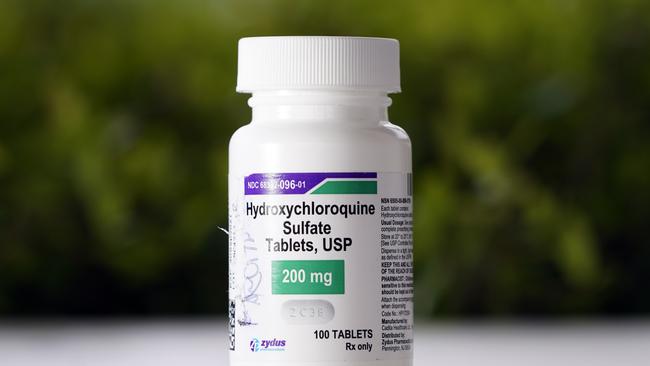

Australians stick with malaria drug hydroxychoroquine trial

Australian researchers are locked in talks to decide whether a major clinical trial of the antimalarial drug should go ahead.

Australian researchers are pressing ahead with administering the controversial antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine in at least one clinical trial despite the World Health Organisation’s decision to discontinue its own clinical study into the medication on safety grounds.

Two major clinical trials are underway in Australia to test hydroxychloroquine’s effectiveness, one as a treatment for COVID-19 and the other as a preventative. The trials have been funded despite the publication of several studies that have highlighted safety concerns over hydroxychloroquine.

The latest paper to cast doubt on the treatment was large-scale study in the Lancet which found people taking hydroxychloroquine were at higher risk of death and heart problems, and that there was no benefit to treating coronavirus patients with the drug.

The ASCOT trial, led by scientists at the Doherty Institute, was to test whether the administration of hydroxychloroquine can prevent patients progressing to severe disease, in a randomised control trial that had hoped to recruit more than 2,000 patients.

The trial’s data safety monitoring committee is now considering whether the trial should go ahead following a steering committee meeting that met late on Tuesday to consider the Lancet paper.

The steering committee had taken into account the comments of the Lancet paper’s authors, who had urged restraint on interpreting the study’s findings.

“The Lancet paper was an observational study not a randomised trial,” ASCOT Trial principal investigator Josh Davis said.

“And so it’s still subject to the same problems of all the other previously published data on hydroxychloroquine, which is that it’s subject to bias.”

“As an example, in the Lancet paper, the patients who received hydroxychloroquine had a higher risk of death at baseline than those who didn’t. They were sicker and they had more comorbidities.

“That alone could potentially explain the higher risk of death. The only way of knowing whether that’s true or not is to do a randomised trial.”

Professor Davis acknowledged that the controversy surrounding hydroxychloroquine may impact on whether patients were willing to participate in the clinical trial. No patients have so far received hydroxychloroquine in the trial, due to a lack of cases.

“So many people have so many opinions about this,” he said. “This may affect participants’ willingness to be randomised to hydroxychloroquine or not, so we need to be very clear about how we’re going to approach this.”

Australian hospitals have turned to hydroxychloroquine in some COVID-19 cases as an experimental treatment, as occurred with Tom Hanks’ wife Rita Wilson in a Queensland hospital. And US president Donald Trump revealed he took the drug for a fortnight as a preventative after a White House aide tested positive to COVID-19. Politician Clive Palmer has imported millions of doses of the drug.

The Federal health department has now issued advice to hospitals that the use of hydroxychloroquine in treating COVID-19 is “strongly discouraged unless the patient is enrolled in a clinical trial”.

The Lancet study was a large observational study of over 90,000 COVID-19 infected patients from six continents and 671 hospitals. It showed a lack of efficacy of hydroxychloroquine and an increase of over 35 per cent of serious cardiac side effects.

The paper compared the outcomes of hospitalised patients who had received one of the antimalarial drugs chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine, or either of those drugs in combination with a macrolide antibiotic such as azithromycin, to those who had not received any of those drug regimens.

The in-hospital death rate in the control group was 9.3%, while approximately 18% died in the hydroxychloroquine group. Of the group that took hydroxychloroquine with a macrolide antibiotic, 23% of patients died. The Lancet paper did not attribute any of the deaths to heart rhythm problems.

Following the publication of the Lancet study on Monday, the World Health Organisation announced it was temporarily suspending testing hydroxychloroquine in a clinical trial involving patients around the world known as the Solidarity Trial.

“The executive group has implemented a temporary pause of the hydroxychloroquine arm within the solidarity trial while the safety data is reviewed by the data safety monitoring board,” Dr Tedros said. “The other arms of the trial are continuing.”

Dr. Michael Ryan, WHO’s emergencies chief, said there was no indication of any safety problems with hydroxychloroquine in the WHO trial to date, but researchers wanted to proceed with “an abundance of caution”.

Research fellow with the Prince Charles Hospital in Brisbane, Roger Lord, said the Lancet study “has shown convincingly that COVID-19 patients treated with these antimalarials are more likely to develop abnormal heart rhythms and die in hospital compared to COVID-19 patients in a comparison group.”

Australian scientists are still confident that proceeding with using the drug as a preventative is safe.

A second Australian randomised control trial, dubbed COVID-SHIELD, led by the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, is currently recruiting 2,250 healthcare workers in 14 hospitals. The doctors and nurses will be asked to take hydroxychloroquine as a preventative against contracting COVID-19. Investigators in that trial have vowed to continue the study, saying they are “very comfortable” with its safety.

“Presently we have no intention to suspend or interrupt our clinical trial,” said co-lead investigators of COVID-SHIELD, Marc Pelligrini.

“And that’s based primarily on the comments that the authors of the Lancet paper made, which was that their results being observational results shouldn’t be over-interpreted, or applied to proper clinical controlled studies.

“They made a distinction between using hydroxychloroquine in people who are very sick, versus those that were not admitted to hospital or who were well. So the extension being that, if you’re giving it to people who well, their trial had no real implications for those studies.

“The other really important thing to stress is that in that particular observational study, no one was doing any screening for potential participants.”

Professor Pelligrini said the Lancet paper showed that the people who started to get heart rhythm abnormalities from taking hydroxychloroquine had pre-existing comorbidities.

“We’re confident that our screening would be able to qualify our study as being very safe,” he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout