How Ray Lawler almost overlooked Australia’s finest stage play

Ray Lawler went each day to the Melbourne Public Library and did nothing but write for one and a half years, creating a ‘state-of-the-nation’ play.

Ray Lawler was the first of our great playwrights, though he was also a fine actor and an important director. There had been others significant plays before, but none before Summer of the Seventeenth Doll had the same effect on our national life.

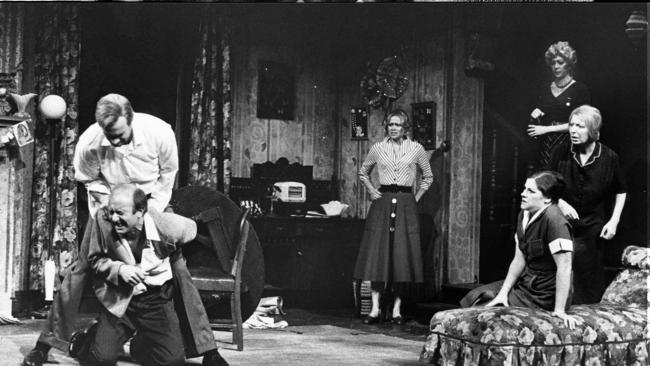

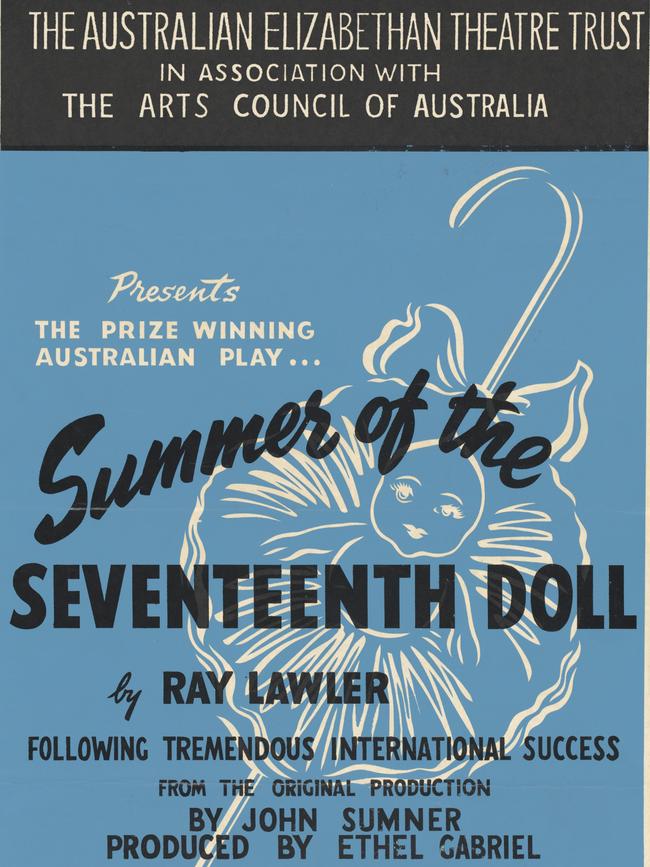

The Doll, first performed in 1955, was a “state-of-the-nation” play at a crucial time of change. (“It’s about them; but it’s really about us,’’ people said in the foyers during its initial run.) It was also Australian theatre’s declaration of independence: actors and writers no longer had to apologise for being Australian.

The production toured Australia and was performed in London and New York, greeted with cheers, stomping and curtain calls. Finally, an Australian play had received the imprimatur of overseas success. The critics at home were silenced as English approval especially guaranteed that the play was acceptable.

Lawler’s rough and ready characters – Olive, Nancy, Roo and Barney – are the cornerstone of our national drama. But in recent years there was a sense that as Lawler himself said, in his characteristically amused-with-the-world way, that the play, in its day regarded as steamy realism, was already seen as “a lavender-and-lace piece of nostalgia”.

Born in 1921, Lawler was the second of eight children, his father an employee with the local council. A childhood fire, at 11 months, gave him severe burns, and a series of medical experiments left him with a bad foot and a crippled little finger.

He was frequently in hospital until he was six.

“I seemed to be the odd one out in the family,” he told me. “Whenever I came back from one of my trips to hospital, there always seemed to be a new baby.”

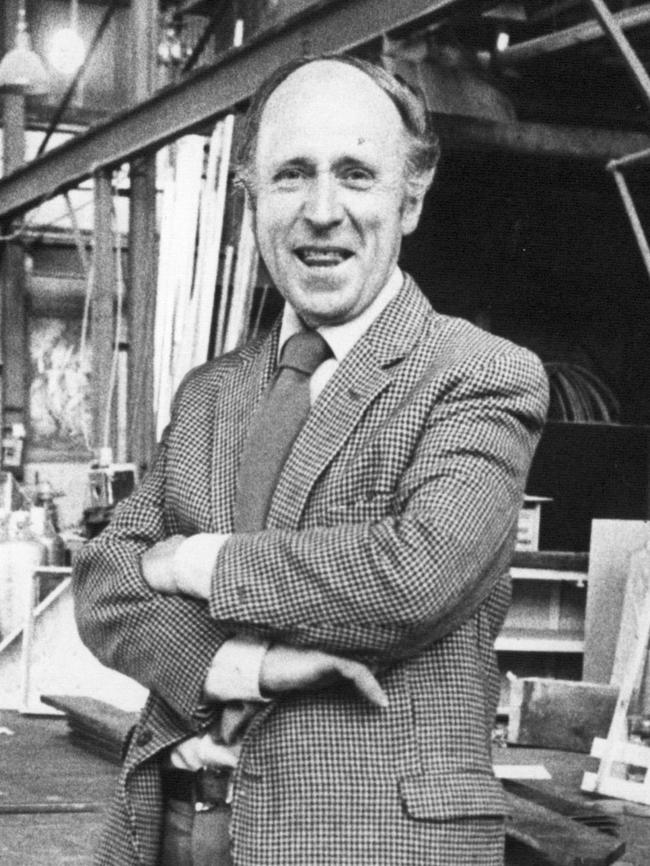

We both worked at the Melbourne Theatre Company in the 1980s, he as literary manager and I as an associate director. We occupied adjacent offices and Ray loved a chat. A veteran actor, he understood that telling stories is our way of keeping alive the glories and miseries of our calling.

He still had an actor’s ways, his voice easily shifting into accents and impressions, and the atmosphere around him was always convivial and inquiring.

“No matter how hard you concentrate on writing, that old actor still wants to get out; it lifts you out of the writer’s doldrums,” he told me when we last met a decade or more ago.

Nobody in his family had the slightest interest in theatre, or art: “I was always aware that I was somehow off on the side, different somehow, and my interest in writing might have started with this.”

At 13, he lied about his age to get a job in a local factory that made agricultural implements. He stayed 11 years on the production line, often on furnaces, then working in munitions factories until the end of the war, which because of his injuries he missed.

From the beginnings of his life, Lawler had a handicap that set him aside from a society in which, at every level, physical accomplishment was instinctively deeply desired. It would become a central idea in his great play as he exposed the infatuation with the values of youth and its physical prowess as such a tragically shallow illusion.

“I had to get out of the factory, and I thought I’m going to write now but I had several tough years before I found theatre work,” he said.

His early ventures were as an actor on local amateur stages, and he even wrote two plays. He didn’t tell many people, he said later, because in those days writing was “a sissy thing to do”.

Those attempts were dominated by the notion that a real play was a sort of light comedy and that all actors must speak with accents as English as they could manage, vowels as rounded and shiny as a new cricket ball.

Somehow, he fell into vaudeville in Brisbane as stage manager and lyric rewrite man for Will Mahoney, a former big-time American variety artist. Then he found his way to Melbourne’s National Theatre in 1949 as an actor and producer. He wrote plays for children, suddenly realising that he was not merely playing to kids but “writing Australian stuff” for an Australian audience.

He threw in his job and, relying on his savings, went each day to the Melbourne Public Library, sitting in the Reading Room beneath its huge copper dome, and did nothing but write for 1½ years.

He wrote two plays: one called The Resignation (he later called it “an emotional outburst”), the other the Doll.

Then, having got it out of his system, it went into the cupboard. He pulled it out in 1954 for the Playwrights Advisory Board Competition for full-length stage plays.

“It shared the £200 prizemoney with another play, The Torrents by Oriel Gray,” he said, still seemingly amazed a play he had forgotten could win anything.

Meanwhile, Lawler had joined Englishman John Sumner’s fledgling professional company, the Union Theatre Repertory Company, soon after it started in 1953.

Barry Humphries, beginning his career as Duke Orsino, toured Victorian country towns with a production of Twelfth Night, directed by Lawler, who also played the clown Feste. Humphries remembered Lawler’s typewriter tapping late into the night after he retired to his hotel room after each show. “We later learned he had been working on a play with a highly unfashionable Australian setting called Summer of the Seventeenth Doll,” Humphries said.

After the play’s success, Lawler left Australia, totally removed from the excitement of the cultural changes taking place, living in a small village in the Wicklow Hills near Dublin.

He returned to Australia in 1975 to work as associate director of the Melbourne Theatre Company with his old friend Sumner, who had directed the original production, with an agreement to complete a trilogy based on the Doll. Composed of the original play and Kid Stakes and Other Times, the trilogy received its first performance at Melbourne’s Russell Street Theatre in 1977.

Lawler is survived by his wife Jackie Kelleher, twin sons Adam and Martin and daughter Kylie.

Raymond Evenor Lawler AO, OBE, born Footscray, Melbourne, May 23 1921. Died July 24, aged 103.