Hospital ‘crisis in slow motion’: Australian Medical Association

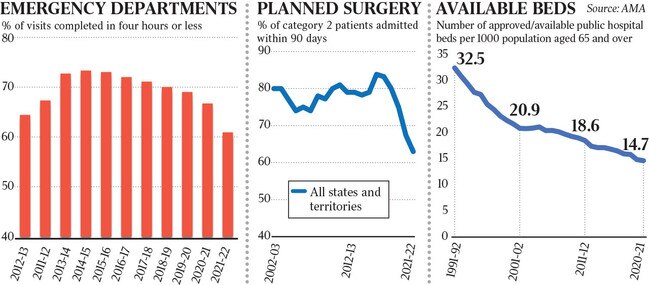

Emergency department wait times at record levels, elective surgery admissions plunge, and beds for the elderly drop to the lowest level in 30 years.

Hospitals are facing a “crisis in slow motion” as emergency department wait times hit record levels, elective surgery admissions plunge, and beds for the elderly drop to the lowest level in 30 years.

Anthony Albanese will on Friday present premiers at national cabinet with the federal government’s immediate plans to strengthen Medicare, with investment in after-hours services the centrepiece of attempts to ease pressure on dangerously overloaded emergency departments.

Primary care providers will be funded beginning in the May budget to continue to provide after-hours care with a particular focus on regional areas where people would otherwise have no alternative but to visit an emergency department.

The extent of the crisis facing emergency departments is revealed in the Australian Medical Association’s public hospital report card for 2021-22, which shows public hospital performance is at its lowest-ever level, with governments failing to accommodate for the explosion in demand being experienced due to the ageing of the population and the rising tide of chronic illness.

The AMA report card shows only 58 per cent of patients with urgent conditions presenting to emergency were seen within the recommended 30 minutes – the lowest level since the AMA began tracking performance in 2002 – often because there were not enough beds.

In all triage categories, only 60 per cent of people who attended emergency were treated within four hours, a 9 per cent decline since before the pandemic.

Almost a million people nationally waited in emergency for longer than nine hours in 2021-22. In Tasmania, the worst-performing state, an average of 35 people every day are occupying beds in the state’s four hospital emergency departments for almost 24 hours while waiting to be admitted to a ward.

Doctors are calling on national cabinet to consider the need for an urgent overhaul of the National Health Reform Agreement which is currently being reviewed midway through its five-year term. The AMA wants performance-based incentives built in to funding models, which are currently based largely on activity.

It also wants a long-term plan to address the issue of the ageing of the population that is beginning to overwhelm hospitals.

“This is the chance to act,” said AMA president Steve Robson. “In just over 10 years, Australia is expected to have more than one million people who will be over 85 years of age and we know older patients are more likely to require an admission to a public hospital. We should be planning for this. But we will remain on the path to failure if we keep doing the same thing over and over and over again.”

The government is also facing a backlash from pharmacy owners over moves to introduce 60-day dispensing for hundreds of medicines, with the Pharmacy Guild asking the Prime Minister ahead of national cabinet “to guarantee to premiers and chief ministers that no patients and no pharmacy in their state will be worse off under the changes”. There are fears, particularly in the regions, that small pharmacies will be hard hit.

Mr Albanese will tell national cabinet that Labor will support new primary healthcare programs with local community organisations that will increase access to primary care services for culturally and linguistically diverse Australians and people experiencing homelessness.

Labor’s support for after-hours programs through primary health networks continues existing services that faced funding termination at the end of this financial year. The federal government will also bolster funding to the Healthdirect helpline, which helps people avoid the need to visit an emergency department after hours.

“Medicare is in its worst shape in 40 years,” federal Health Minister Mark Butler said ahead of national cabinet. “Being able to access a doctor after hours is critical for patients.”

The AMA has also compiled evidence that hospitals are operating at capacity and warned there must be an immediate plan to address the needs of the elderly.

Despite the growing proportion of older people who are increasingly filling wards, the number of hospital beds per head of population has been declining for eight years, causing a knock-on effect as emergency departments become holding spaces and ambulances ramp outside hospitals.

People aged 65 and over now make up almost 17 per cent of the population and account for half of all patient hospital days. Yet in 2021-21 the ratio of total public hospital beds for every 1000 people aged 65 years and older was 14.7, less than half what it was three decades ago.

“With the number of Australians aged 85 and over expected to exceed one million by 2035, and with the hospitals already operating at capacity, Australia’s public hospital system is at risk of becoming unsustainable,” the AMA’s report card says.

“This ratio of total public hospital beds for every 1000 people aged 65 years and older has now been on a downward trend for 27 years and is a major cause of public hospital overcrowding and long waiting times.

“These numbers show that Australia’s shifting demographics are having a significant impact on the public hospital system. Australia needs a broader discussion at the national level on whether Australia’s public hospital policy and funding settings are still adequate.”

The demographic challenges were compounded by social policy failures, with almost 20,000 elderly people clogging hospitals, unable to be discharged due to a lack of aged care and community support, with others discharged to “unsafe or unsuitable destinations” that increase their risk of readmission.

Hospital performance is not improving in elective surgery.

Nationally, fewer than two out of three people requiring semi-urgent surgery in public hospitals in 2021-22 were treated within the target of 90 days, despite a modest improvement against that target.

Despite efforts to catch up on elective surgery backlogs, in 2021-22 public hospital admissions for elective surgery were lower even than the first year of the pandemic, and 135,000 fewer people were admitted for surgery than in 2018–19, with “hidden waiting lists” of hundreds of thousands of people who cannot access outpatient services also exploding.

“That’s more than one in three patients waiting longer than the clinically indicated time for essential surgeries, often in terrible pain and unable to work,” Professor Robson said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout