Patient costs soar as the Medicare debate heats up

The poorest patients are spending the largest proportions of their incomes on out‐of‐pocket fees for health care as private costs soar in Australia.

The poorest patients are spending the largest proportions of their incomes on out-of-pocket fees for healthcare as private costs soar in Australia above similar countries and the debate over the future of Medicare gathers pace.

A recent article in the Medical Journal of Australia found one in three low income households was spending more than 10 per cent of total income on healthcare. The article by James Cook University public health researcher Emily Callander found “individuals do forgo care, with one in four Australians without a healthcare condition and up to one in two with certain health conditions avoiding care because of the cost”.

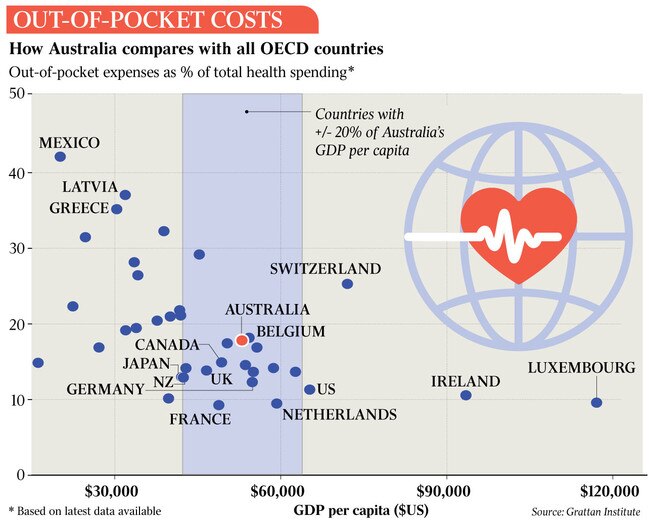

The research found private contributions to healthcare in Australia by patients was double that of the private health insurers. Australia’s out-of-pocket costs, amounting to an estimated 17 per cent of all national expenditure on healthcare, are higher than those in New Zealand, Ireland, France, Germany, The Netherlands and Britain.

“The ability of private providers of healthcare services to set their own fees, to cover operational costs and make profits, is a key feature of the Australian healthcare system,” Associate Professor Callander writes. “This is supported by the Constitution, with government excluded from regulating fees that healthcare providers charge for their services.

“The fee charged, and the amount of profit, is therefore determined by an individual consumer’s willingness to pay for the service. In the market, the higher the willingness to pay, the higher the service fee.

“This is problematic in healthcare as willingness to pay is constrained by ability to pay, with people at socio-economic disadvantage, who generally have poorer health, having a lower ability to pay the higher prices often paid by those at socio-economic advantage.”

The idea the Constitution limits the executive’s ability to play a greater role in the regulation of healthcare was this week challenged in a paper by QUT health law academic Fiona McDonald and health economist Stephen Duckett, who said the commonwealth could restrict access to some Medicare billing items only to GP practices that opted in to a voluntary scheme in exchange for agreeing to bulk-bill all patients, while other doctors’ access to Medicare would be restricted and they would be left to bill wholly privately.

The suggestion rankled many doctors and is opposed by the Australian Medical Association, although Doctors Reform Society president Tim Woodruff welcomed “these great suggestions which are indeed radical but intended to achieve the very mainstream idea of health equity, i.e. equal access to equal care for equal need”.

Dr Woodruff added: “This proposal will take time to implement. The government could today increase the existing miserly incentive payment for bulk billing for pensioners and healthcare card holders to reduce the suffering and neglect increasing daily in the community as bulk-billing rates fall across the country.”

AMA president Steve Robson said it was beyond dispute that Medicare needed fundamental reform. “We all know what is needed: better indexation of Medicare and reform to consultation items to ensure GPs can spend the time they need with patients.”

“We estimate that since the beginning of the MBS freeze, close to $4bn of funding has been lost from general practice around the country, and that’s funding that goes to Australian patients who are seeing doctors,” Professor Robson said.

“The result of the $4bn cut to funding is a situation where Australia’s most vulnerable patients have trouble accessing general practice. Conscription is not the answer and will only exacerbate the challenges faced by general practice. We need carrots, not sticks to improve access to general practice.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout