Honouring the firefighter heroes who walk quietly among us, saving lives, protecting homes

The volunteer firefighters of Australia are, collectively, this newspaper’s Australian of the Year.

They come from all walks of life, from every corner of a wide, brown land.

They are somebody’s son or daughter, brother or sister — and they’re everyone’s saviour.

They are family because they fight for us; and we have never needed them more than during this terrible, terrifying summer as bushfires killed 33 people so far, destroyed nearly 3000 homes, blackened the landscape and licked at the doorsteps of capital cities.

They stood up and stood strong. Without them, more lives and property would have been lost, countless more tears shed. They sweated and suffered for others while their own homes burned. Some died.

They are the volunteer firefighters of Australia, the pride of a grateful nation. And collectively they are this newspaper’s Australian of the Year.

Editor-in-chief Christopher Dore said: “These men and women collectively represent the spirit of modern Australia, capture our history of bravery, sacrifice and service, and remind us of our unique connection to land held so dear by indigenous Australians.

“The firefighter also represents an optimism that has come to epitomise the Australian character, an air of dogged determination and admirable aspiration that has made us who we are and will continue to define us as a nation in the decades ahead.”

Here stand four of them, ordinary people who do extraordinary things when they don the yellow, Proban-treated bush jackets of the NSW Rural Fire Service.

Cornice fixer Darren Nation, 43, is a gun on the hose, the one you want by your side in a jam; electrician Anthony Ciccaldo, 35, is never off the phone or the radio checking that everyone else is OK; count on engineering shop owner Sam Quattromani, 48, to tell it like is, no matter what.

Blake Kingdom, 22, a full-time operational communications officer with the RFS, part-time member of the Horsley Park brigade in Sydney’s west, hasn’t experienced anything like the bond between volunteer fireys.

“The whole brigade is like one big family and they have taken me under their wing,” he said.

“They’re my parents, my brothers and sisters, my mates all rolled into one. You literally trust them with your life.”

How they’ve been tested this fire season, a blur of deployments as teams were sent north, south, east and west to confront one emergency after another. But there’s a day they will never forget: Thursday, December 19. Two of their own didn’t come home after a burnt-out tree crashed down on Horsley Park One-Alpha, the brigade’s category-1 bushfire appliance, killing Geoffrey Keaton, 32, and Andrew O’Dwyer, 36.

The tragedy poignantly demonstrated to a shocked nation the sacrifices made by the volunteers — for no pay, at the cost of Christmas holidays, time with their loved ones and in the face of consuming danger. Thursday’s crash of a chartered C-130 Hercules waterbomber in the Snowy Mountains, killing all three US crew, took to nine the number of firefighters who have died since the bushfire crisis erupted last September.

All too often firefighters have been the last line of defence between imperilled communities and the advancing flames, saving the day when all seemed lost.

Sometimes, though, things just go horribly wrong. It was like that for Keaton and O’Dwyer, Mr Quattromani said, his voice raw with emotion. They relieved his crew on the evening of December 19 outside Buxton, a hamlet in the NSW Southern Highlands an hour’s drive southwest of Sydney that was ringed by fire. Mr Quattromani’s team was exhausted. They had been hard at it since first light, battling the huge Green Wattle Creek blaze. “We had our arses handed to us,” he said.

He threw the keys of One-Alpha, the big Isuzu mounting a 3300L water tank, to Keaton, who had taken over as driver. O’Dwyer, the crew commander, took the seat next to him. Carlos Quinteros, Ben Fraser and Tim Penning climbed into the back of the cabin. Mr Kingdom was supposed to make up the regulation six but he had been switched to another truck at the last minute by fire control centre, a twist of fate that continues to weigh on him.

Mr Quattromani warned his friends to be careful. “It’s shit out there,” he told them.

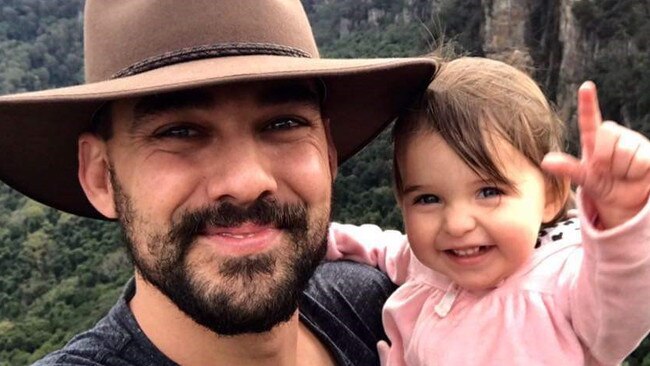

One-Alpha was second in a convoy of five RFS trucks that headed along Wilson Road, fringed by a charred and still-smoking forest that shimmered eerily in the moonlight. The tree fell, crushing the front of the white-roofed tanker. Keaton and O’Dwyer, both fathers of young children, died at the scene; the others escaped serious injury. Mr Nation’s phone rang when he was in bed, catching up on some sleep. He has 26 years of active service with the Horsley Park brigade, the past three as captain, but he never thought he would have to deal with news like this. “It was disbelief,” he recalled. “You turn out to a fire and you never expect not to come home, and I don’t expect my crew members not to come home, either.

“Yes, you know it can be dangerous and you can’t control everything, but we are very, very well-trained, well-equipped. We have confidence in that and in each other.”

The grief hit like a hammer blow. Keaton, the son of a firefighter, was a good friend — they had been camping and fishing together. But O’Dwyer was something else, the best man at Mr Nation’s wedding. He had always been there for him personally and as a leader of the brigade.

“We just clicked … he was my best mate,” Mr Nation said quietly.

Mr Ciccaldo, as senior deputy, got the brigade members together. What now? RFS command was suggesting they stand down, but he agreed with Mr Nation that Keaton and O’Dwyer wouldn’t want that. Mr Quattromani said: “When you fall off a horse, you get back on it.”

So on Saturday, December 21, Horsley Park’s six longest-serving firefighters loaded up one of the spare trucks and drove back out, led by Mr Nation.

Mr Ciccaldo found it unnerving to be in the scorched and denuded countryside knowing what had befallen their friends.

“We wanted to make a show of force to the brigade,” Mr Ciccaldo explained. “We were still needed, and we could still do the job. It was the right thing to do to get out there … and we, the senior members, wanted to set the example.”

Mr Quattromani was turning over in his mind those last, hurried exchanges with Keaton and O’Dwyer on the night they died. A sense of guilt gnawed at him. Rationally, he accepts that no one was to blame for the deaths. “It was not my fault the tree came down,” he said. “But I … was in charge and I gave them the keys to the truck. I keep thinking, you know, with hindsight, that maybe I shouldn’t have let them go.”

Mr Kingdom also wonders what would have happened had he stayed on One-Alpha. Could he have shouted a warning or helped his stricken mates?

“I have this sense that it should have been me … that I should have been there, with them,” he said. “I cried and cried after I heard about the accident.”

Mr Nation spoke of his pride in how the 70-strong brigade pulled together in the weeks that followed, its members aged from 16 to 60, numbering tradies and IT specialists, police officers, retail staff, students and retirees — a microcosm of the 150,000-plus Australians who belong to volunteer firefighting units. “It made us a lot stronger as a team and a family,” the veteran captain said this week as crew members drifted in for the weekly training session at the Horsley Park station house.

“We sort of needed to be there for each other, and for the families of Andrew and Geoff, their wives and kids, when they are trying to deal with everything. It’s brought us so much closer together because we know that everyone is hurting and everyone is feeling the pain.”

On January 17, O’Dwyer’s widow, Mel, and his father, Errol, joined Mr Ciccaldo, Mr Quattromani and others from Horsley Park for the long, sad bus ride to the funeral of Sam McPaul, the 28-year-old RFS man killed on December 30. Tornado-like winds generated by an inferno at Jingellic, east of Albury, on the NSW-Victoria border, had flipped his eight-tonne truck as if it were a toy.

They watched in solemn silence while McPaul’s widow, Megan, pregnant with their first child, was presented with her husband’s posthumously awarded bravery medal by RFS commissioner Shane Fitzsimmons.

Scott Morrison and NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian led the mourners.

Why do it? Why risk your life, all that you love and cherish at home, to protect the neighbour you barely know or a stranger you’ll never meet? Pausing to gather his thoughts, Mr Nation answered: “I think you do it because you love it. Once you start, it’s in your blood. You do it because you can help people and the smallest thing can make the biggest difference to someone’s life.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout