Home truth about homelessness

Melbourne mother Amanda Bingham worked in administration roles in offices for more than a decade before switching into childcare. Then her life went into a tailspin.

Melbourne mother Amanda Bingham worked in administration roles in offices for more than a decade before switching into childcare. She started a nannying business in Melbourne’s salubrious Albert Park, and was studying to be a doula.

Then, as she says, she met the wrong man, and her life went into a tailspin.

“There was domestic violence. I tried several times to leave, but I didn’t have family to fall back on, so I went back to him. The option of sleeping in my car was quite difficult,” she says

On one occasion, in a particularly down moment, she almost crashed her car into a truck. The driver was kind, she says. He stopped and they talked.

“He helped me that night, let me sleep at his place. The days turned to weeks, then months. That’s where Daniella entered the picture.”

Ms Bingham, now 45, fell pregnant with her daughter Daniella, now 3. But the relationship didn’t work and she found herself pregnant and once again homeless.

“I sought the support of Reach Housing. First I was in a women’s shelter, then in a nunnery for a few weeks. At the end of my pregnancy they found me transitional accommodation. I’m still there,” she says.

Ms Bingham continues to look for permanent housing through a support worker, but supply is scarce. As well as advocating for better support services for women, she has been accepted into a course at RMIT next year to do a diploma in community services case management. “I’m trying to use my lived experience plus the course to get a good job as a case manager for women like myself needing support,” she says.

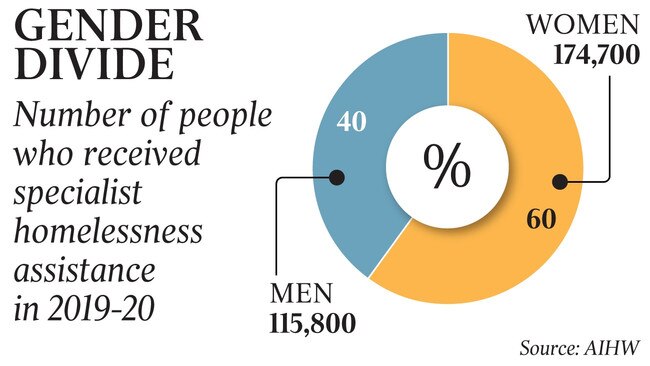

Last financial year in Australia, specialist homelessness services provided support to more than 290,000 clients, according to new research by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Sixty per cent were women, almost 30 per cent were younger than 18 and 30 per cent had at least one mental health issue.

The problem seems intractable, despite the attention paid by successive governments at state and federal levels and millions of dollars of additional funding poured into the sector during COVID-19.

“Between 2015–16 and 2019–20, the number of clients helped by specialist homelessness agencies increased by an average of 1 per cent a year from 279,200 to 290,500 people,” AIHW spokeswoman Gabrielle Phillips says.

“In 2019–20, about 114,000 clients were homeless when they first presented to services seeking help and 152,300 were at risk of homelessness.”

Despite the high numbers being provided with support, demand is far in excess of supply, Homelessness Australia chair Jenny Smith says.

“In 2019-20, every day 260 people seeking support missed out. Over two-thirds were women or girls,” Ms Smith says.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout