Workers wanted urgently: enough job vacancies to clear dole queue

Hiring frenzy hits top gear as employers seek to fill almost half a million jobs, amid chronic worker shortages and lowest unemployment rate in nearly 50 years.

Australia’s staffing shortage crisis has worsened with almost half a million jobs going begging and the number of vacant positions now nearly equal to the number of unemployed.

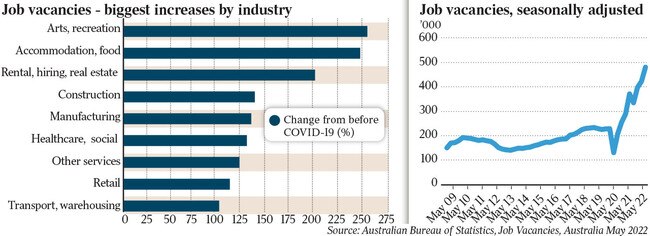

Industry groups on Thursday called for “urgent” action by federal and state governments to make it easier to bring in foreign workers, and to allow older Australians to work more hours without losing their pension. The number of job vacancies reached a record 480,000 in May, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, a jump of 14 per cent since February and more than double pre-pandemic levels of about 225,000. There are currently 548,000 people who declare themselves as jobless.

Business Council of Australia chief executive Jennifer Westacott said “a shortage of workers puts a handbrake on businesses who want to expand and innovate, boost their productivity and pay sustained higher wages”.

“It means customers face long waits when travelling, they can’t get reservations at their favourite restaurants and cafes, or they can’t access the services they want,” Ms Westacott said. “You can’t employ hundreds of Australians on a construction job if you don’t have a surveyor, you can’t deliver an infrastructure pipeline without engineers, and you can’t open your restaurant or cafe if you don’t have the staff.

“We need both targeted migration to fill critical shortages at every skill level right now, and a skills system that lets workers easily and quickly train with the skills employers need for the longer term.”

ABS head of labour statistics Bjorn Jarvis said the big quarterly rise “reflected increasing demand for workers, particularly in customer facing roles, with businesses continuing to face disruptions to their operations, as well as ongoing labour shortages”.

Mr Jarvis said there was now “almost the same number of unemployed people and vacant jobs in May 2022, compared with three times as many people before the start of the pandemic”.

Ahead of a winter school holiday period which is predicted to be marred by major disruptions and delays at airports fuelled in part by staff shortages, industry groups warned a chronic lack of staff would drag on the economy as firms struggled to keep pace with demand.

The number of vacancies began rising steeply across the country from late 2020.

Over the past 18 months employers have scrambled to rehire staff and put on additional employees as the economy recovered after the end of Covid-19 lockdowns, fuelled by massive fiscal and monetary policy stimulus.

Closed international and domestic borders flattened migration and labour mobility, exacerbating the staffing challenges which remain acute in 2022.

In Western Australia, which has had the country’s tightest border controls, the ABS data showed there were 40 per cent more job vacancies than there were officially unemployed West Australians – or a ratio of 1.4 job vacancies in the state to unemployed.

This was tighter labour market than during the mining investment boom, when even at its peak the unemployed outnumbered vacancies, if only marginally.

Nationally the ratio of job vacancies to unemployed people – as measured by the ABS – was 0.9, and at similar levels in NSW and Victoria. The lowest ratio was 0.6 in South Australia.

Theoretically, filling the additional roughly 255,000 additional jobs on offer nationally versus pre-pandemic would halve the unemployment rate to 2 per cent. Filling all the positions with 548,000 currently jobless Australians would drive unemployment to near zero. Overall, the figures showed the challenge to find workers remains a pressing one. One in four businesses reported at least one vacancy in May, versus one in 10 in February 2020.

While 80 per cent of firms said they were looking to fill positions left vacant by resigning staff, that was only slightly higher than before the health crisis.

The next most frequent reason was the need to hire due to a greater workload, at 47 per cent and well above the 36 per cent pre-pandemic – suggesting that higher demand for goods or services was a prime motivation to advertise for new staff. (Businesses could report multiple reasons for reporting job vacancies.)

The sectors hardest hit by Covid-19 restrictions reported the biggest increase in vacancies since the pandemic struck, with the arts and recreation and hospitality industries looking to fill three-and-a-half times more vacancies than in February 2020, according to the data.

Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry chief executive Andrew McKellar said the worsening “labour and skills crisis” was “holding back business and holding back the economy”.

“In light of chronic workforce gaps, businesses have turned to existing employers to work additional hours where possible, reducing their operating capacity, or closing their doors entirely,” Mr McKellar said.

Jim Chalmers, speaking from Lockyer Valley in Queensland, said the shortage of farm workers – alongside higher transport and fertiliser costs – were together “driving prices up in our supermarkets and having real impacts for Australians, right around the country”. The Treasurer told Sky News “we’ve got to deal with issues around the resilience of supply chains, we’ve got to deal with labour movement, labour mobility, labour shortages – we have to deal with that”.

Australian Retailers Association CEO Paul Zahra said his industry recorded the highest increase in vacancies of any industry, and called for “urgent” federal and state action to ease the pressure on employers, through such measures as making it easier to bring in foreign workers and for older Australians to work more without losing their pension.

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton recently joined business groups in pushing for a change in rules about how much a pensioner can earn before having their payments reduced – a measure that was considered but ultimately not taken up by the former government.

ANZ senior economist Catherine Birch said she was surprised by the surge in vacancies over the three months to May, particularly in the context of some return of migration. Ms Birch said that with household spending set to remain resilient despite rising interest rates this year, there was no “silver bullet” to solving the unprecedented staffing challenge facing companies. Even returning immediately to pre-pandemic net migration levels of 240,000 would not solve understaffing when considered in the context of 480,000 job vacancies, she said, especially when not all migrants were workers, and they added to the overall level of demand in the economy.

The upside to worker shortages was the unemployment rate would continue to push lower, from 3.9 per cent in May to the “low 3s” over the coming months, and stay around these levels into 2023, Ms Birch said.

More Coverage

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout