Hinch defiant on Dunstan wife broadcast

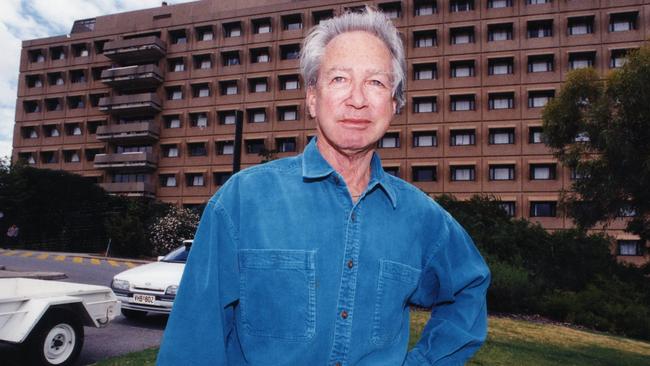

Derryn Hinch stands by his explosive 1978 broadcast on the late SA premier Don Dunstan’s wife.

An unrepentant Derryn Hinch has stood by his decision to broadcast details of the terminal cancer diagnosis given to the second wife of the late South Australian premier Don Dunstan in an explosive broadcast in the late 1970s.

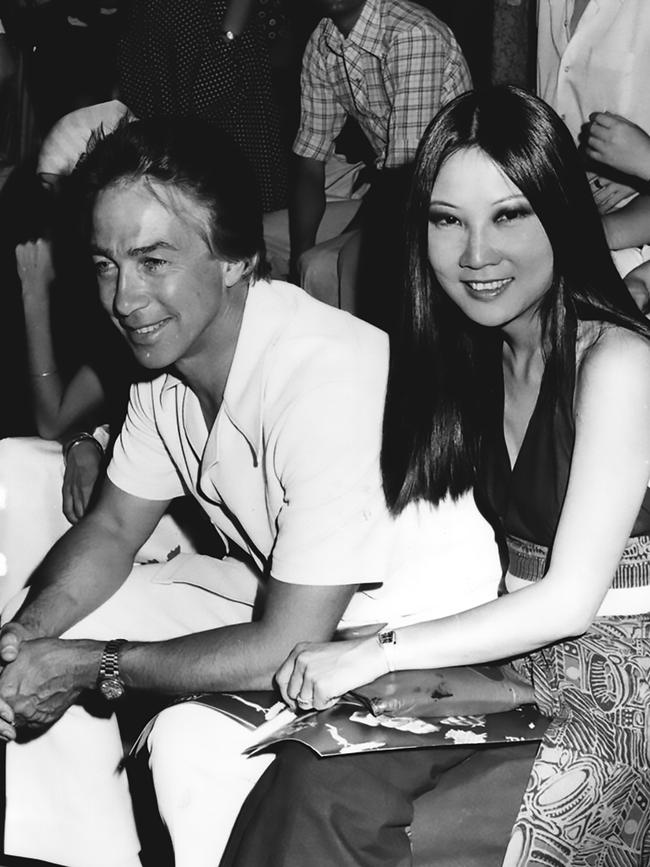

Five months before the death of Adele Koh in October 1978, Hinch used his talkback program on Melbourne radio station 3XY to reveal that the glamorous Malaysian-born journalist, who married the former premier in 1976, was dying.

Hinch’s broadcast breached one of the most extraordinary but well-meaning cover-ups Australian journalism had seen, with every Adelaide news organisation knowing about Koh’s diagnosis but declining to reveal details at the personal request of the devastated premier.

Even when Hinch made the revelations, no SA media outlet reported the news until Kho died on October 24 that year.

MORE: Inquirer special; Dunstan’s seriously wild ride | Dunstan’s sordid and secret affairs

A new biography of Dunstan by historian Angela Woollacott, the Manning Clark Professor of History at the Australian National University, documents the extent to which Dunstan hated Hinch as a result, accusing him of hastening his wife’s death.

“This piece of bastardry did affect her condition markedly and I have never forgiven him,” Dunstan said after Koh ’s death.

Hinch was unrepentant at the time. “I never made a deal,” he said. “She’s a public figure, she’s the wife of the premier.”

Yesterday, Hinch said it was a disgrace the media had agreed to go along with Dunstan’s request, saying he had “no qualms whatsoever” about his actions. He said it was a valid political story because it involved a public figure.

“I wasn’t calling for people to be intrusive and to go and get photographs of her in her hospital bed,” Hinch told The Australian.

“The reason it was a political story is Dunstan had managed to cow the Liberal opposition into going easy on him, at a time when his government and his conduct were starting to unravel.

“There has been plenty of examples of the media rightly reporting on issues involving the illnesses of political partners, such as Betty Ford when she was first lady, and this was no different.”

In her biography Don Dunstan: The visionary politician who changed Australia, Professor Woollacott reveals the remarkable extent to which Dunstan pleaded with the SA media to prevent any reporting of the story, which led to a formal ban by then media union the Australian Journalists Association that applied to interstate news organisations.

“The Adelaide media were remarkably considerate of Koh and Dunstan,” she writes.

“Word about her illness circulated as soon as she had the tests in hospital. Papers immediately asked the premier’s office for comment, but Dunstan personally intervened. He was very concerned that Adele not be troubled by press reports about her terminal condition. Dunstan phoned the editors of the two major local newspapers, The Advertiser and The News, and asked them not to print the story.”

Hinch said Dunstan’s own retirement from ill-health the following year made his decision to broadcast the news even more compelling, suggesting Dunstan’s own health had suffered.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout