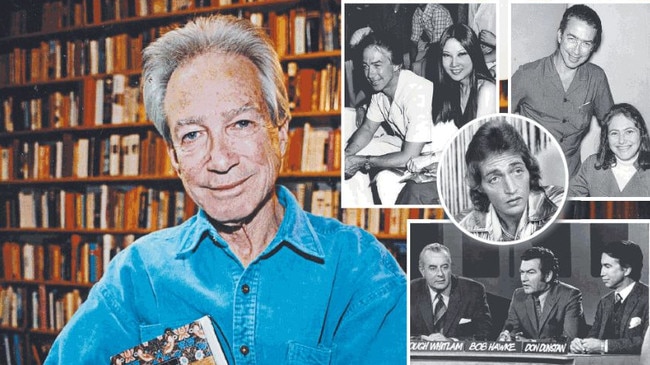

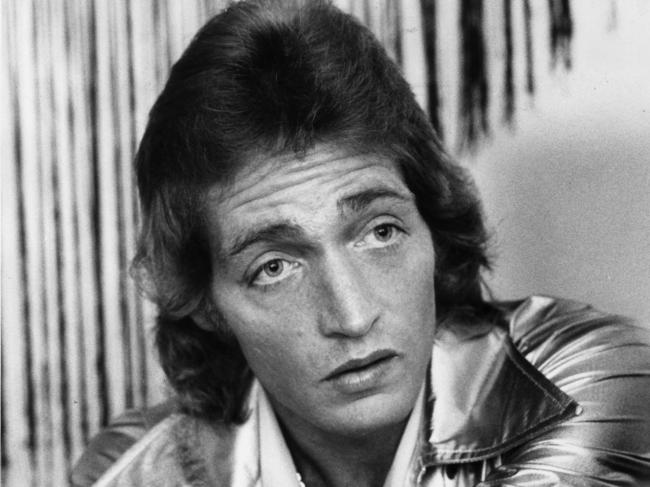

Don Dunstan: The power and the passion

In the space of a few years in the 1970s, Don Dunstan separated from his first wife and had at least four passionate affairs. All while he was South Australian premier.

In the space of a few years in the 1970s, Don Dunstan separated from his first wife, had at least four passionate affairs — with a Brazilian actress, a Greek female union activist, a male member of his staff who later became a heroin addict and the female partner of his artist friend Clifton Pugh — while writing a cookbook that likened making a meal to making love.

All while he was South Australian premier.

Giddy with joy, Dunstan had celebrated the end of a 1972 performance of the musical Hair at Adelaide’s Her Majesty’s Theatre by jumping on stage and dancing with the cast during its final number, Let the Sunshine In.

MORE: Secret affair with Judith Pugh | Hinch defiant on Dunstan wife broadcast

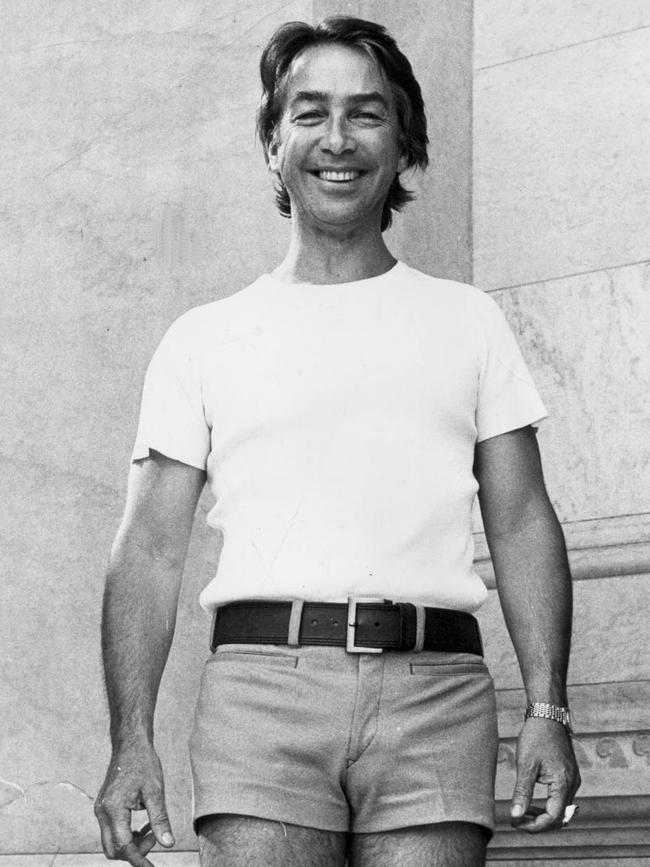

Against the admonitions of his advisers, he had been photographed on the steps of state parliament wearing hot-pink shorts and a tight, white muscle shirt tucked into his belt, proudly showing off the pecs he had been cultivating at an Adelaide gym — after a youth plagued by teasing over his puny chest. He had endured and ignored growing rumours about his sexuality, spread by his establishment detractors who tried to cruel his initial foray into politics with a whispering campaign describing Dunstan, born in the Fijian capital of Suva in 1926, as “a Melanesian half-caste bastard”.

Reforming a staid state

Amid all this, Dunstan remained one of the most popular premiers South Australia has seen, in what was then the most conservative state in the Federation.

He had done so with a social agenda that to this day remains anathema to many conservatives. Yet from his election as Labor leader and premier in 1967, after the retirement of the ageing incumbent Frank Walsh, and to winning back power in his own right against moderate Liberal premier Steele Hall in 1970, Dunstan would govern South Australia unassailably until his sudden retirement from ill-health in February 1979.

How did such a staid and stodgy state, with its roots in Methodism and Lutheranism and ruled for decades by old money and a gerrymandering rural squattocracy, sign up with such enthusiasm for the Dunstan Decade?

The answer, according to the author of his new biography, lies with Dunstan himself, both in his force of character and the strength of his convictions.

Historian Angela Woollacott, the Manning Clark professor of history at the Australian National University, was born and reared in Adelaide and had a front-row seat for the Dunstan era. A graduate of Unley High School — the alma mater of former prime minister Julia Gillard — Woollacott says it remains remarkable that Dunstan achieved so much reform in a state that had been so averse to change.

Conviction politician

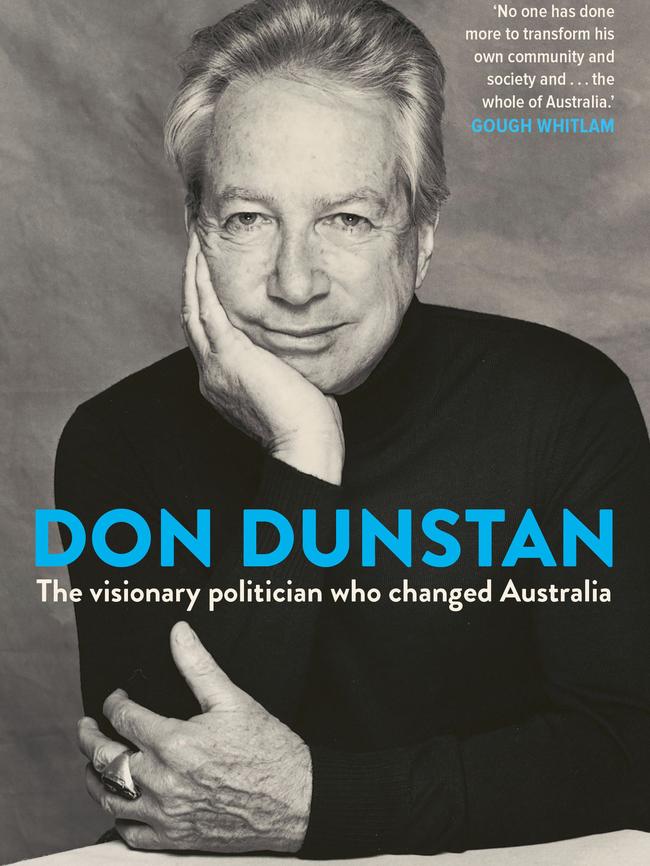

In her book Don Dunstan: The Visionary Politician Who Changed Australia, Woollacott says Dunstan did so because he stuck to his principles and brought the public along with him.

“It was a combination of his strong convictions and a very clear agenda, and the fact that he was so good at enacting that agenda, that made him succeed,” Woollacott tells The Australian.

“Today so many people express jaundice with the political system because politicians often seem to be driven by rivalries or self-interest rather than clearly following an agenda. Dunstan had a very clear agenda. Once he developed his set of principles, he stuck to them for the rest of his life.

“He could explain things in clear and compelling terms so that ordinary voters understood why he was following a certain objective. He could explain the benefits. He was a conviction politician. And he became a national leader at a time when SA punched above its weight.”

Admirers and detractors of Dunstan would agree that his impact on social policy was profound. In many ways the battlelines of the modern culture wars were drawn by Dunstan, with his championing of the Racial Discrimination Act, equal opportunity and sex discrimination laws, the first land rights legislation recognising native title, the decriminalisation of homosexuality, all of them firsts in South Australia and subsequently followed nationally.

Less contentiously, but of equal national significance, Dunstan played a lead role within Labor in the 1950s in scrapping the White Australia policy. Woollacott quotes the late Bob Hawke who, on Dunstan’s death in 1999, said: “Don argued that this policy was morally repugnant, and with a prescience about the importance of Asia to Australia’s future, that it was economically insane.”

Informed by his childhood in Fiji and his return there as a young adult after graduating from law at the University of Adelaide, Dunstan pre-dated Paul Keating as an advocate of engagement with Asia, establishing a pioneering sister-city relationship between Adelaide and Penang, and advocating increased foreign aid to the Pacific.

Social change agent

And on the lifestyle front, Dunstan was a trailblazing bon vivant, the likes of which Australia had never seen. He scrapped the 6 o’clock swill, brought in BYO laws and alfresco dining, ramped up arts funding, championed a food and wine culture (from 1968 to 1983 the number of Adelaide restaurant licences went from 30 to 401), and he opened Australia’s first nude beach. He destroyed the stultifying, lace-curtained Adelaide he documented with such disdain in his memoir, Felicia.

“The government and the supporting establishment excised great pressure to conformity,” Dunstan wrote. “In 1950 licensed restaurants could serve liquor ’til 9, but at that time your glass was whisked from the table whether you had finished your meal or not. It was well-nigh impossible to find an eating place open in Adelaide after 7pm, other than street carts selling meat pies and pea soup, on Sundays everything closed.

“The whole state appeared shrouded in Calvinist gloom … it was considered improper to enjoy oneself. SA had little significance for the rest of the country — it was regarded as a backwater — the “Wowser” state. ‘I went to South Australia’, ran the popular saying elsewhere, ‘and it was closed’.”

One of the curious features of Dunstan’s achievements was that he succeeded in public life despite his flamboyance, at a time when the Liberals were dominated by gentlemen graziers and sherry-soaked members of the Adelaide Club, and Labor was the preserve of gruff, chain-smoking men with hard hands who came up through the unions in the then dominant manufacturing sector.

Dunstan sat awkwardly in both cultures; if anything, he seemed more destined to become a Liberal than a Labor man, later describing himself as “a refugee from the establishment”.

His parents were conservatives, although their politics later changed in support of his political career, and in Fiji he had servants at home and attended the elite Suva Grammar, a bastion of white privilege.

On moving to Adelaide in his early teens he studied briefly in Murray Bridge, where he took elocution classes at his parent’s behest.

“When Dunstan was advised by at least one ALP mentor to drop the upper-crust accent, he refused, saying his parents had paid quite a bit for it,” Woollacott writes.

Bird of paradise

He finished his education at what remains the state’s poshest private school, St Peter’s College, where the young Dunstan dismissed its obsession with uniforms and behaviour as “idiotic”, its focus on sport “a nonsense”, and at one stage he refused as a prefect to discipline a group of boys caught wagging at a local milk bar.

He was average at mathematics and science but excelled at English and drama, finding solace with an elegant gang of like-minded outsiders who loved poetry and theatre, and referred to themselves as “the birds of paradise”.

His passion for the arts continued into his studies at the University of Adelaide, where he also became an active member of the Labor Club and Fabian Society, and an outspoken and articulate anti-communist. It was there that he met his first wife, Gretel, whom he married in June 1949 when he was just 22 and she was 19.

As with the memoir by Robert Hughes, where the legendary art critic reveals his pain at enduring the infidelities that come with polygamy, Woollacott’s biography provides an often eye-opening account of the byzantine nature of Dunstan’s personal relationships and the emotional hardships that came with an open marriage.

The Dunstans’ marriage lasted for 23 years and produced three happy, successful children who were brought up with books and music. But while their marriage was regarded externally as unremarkable, the truth inside was anything but that.

Influenced by their reading of French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre and his philosopher partner Simone de Beauvior, and Bertrand Russell’s 1929 book Marriage and Morals, which questions the underpinnings of monogamy, the Dunstans resolved to live by the proviso that “infidelity was all right if you told the other person”.

Despite these rules of engagement, and despite the fact by this stage Don Dunstan was describing himself as “ambisexual” and acting accordingly, he was devastated when Gretel informed him that she had an affair with an ALP activist from Queensland named Barry Salter, who would somehow subsequently become a good friend of Don.

The final breakdown of the marriage in 1972 followed spectacular public rows, and once the pair had separated, Dunstan’s continuing tenure as premier coincided with a private life that made the plot of Don’s Party look as sedate as an old re-run of Blue Hills.

The over-muscled male

Aside from the aforementioned Brazilian actress, the Greek unionist and Judith Pugh, the most confronting and reckless of Dunstan’s dalliances was with a young man by the name of John Ceruto, who later would succumb to heroin addiction and collaborate on a damning book about Dunstan entitled It’s Grossly Improper.

Ceruto, who first entered Dunstan’s circle around 1968 but re-emerged in earnest in 1972 when the premier had split with his wife, was memorably described by the premier’s press secretary and then friend Peter Ward as “a dumb, strutting, over-muscled male blond, practically illiterate and without social skills”.

Smitten, Dunstan ignored the advice of Ward and others and appointed Ceruto to a dubious job as tourism adviser in the Premier’s Department.

Ward, who would later serve with distinction as The Australian’s South Australian correspondent, wrote an explosive, relationship-ending letter to his boss about the appointment.

“The news of your separation from Gretel was delicately handled only because we got the editors in and got them on-side in that way … the truth is that people really do believe you are f..king John, and it is a very dangerous rumour because there does not seem to be any other explanation for your close friendship with such a strange, young man. What I am trying to explain is that, in your position now, single, lonely, the advent of John is good copy for newspapers.”

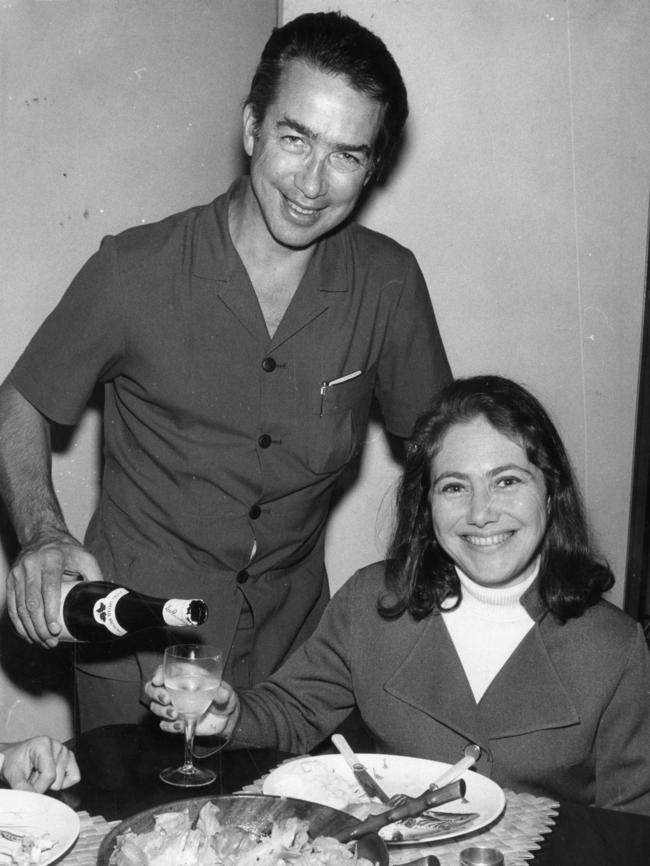

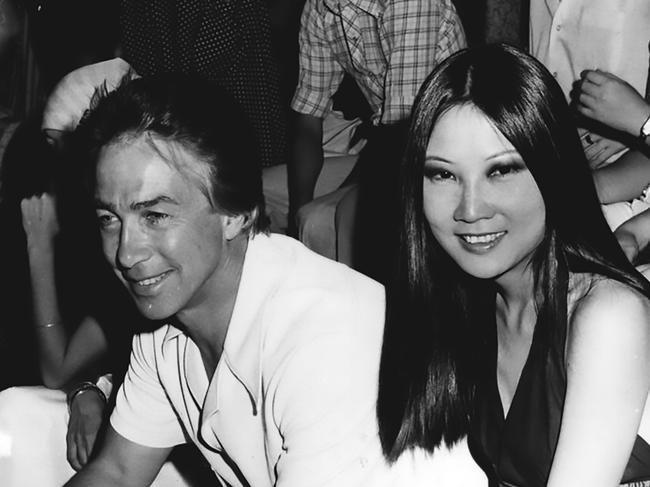

None of that copy eventuated, in the same way that no one in the Adelaide media would dare reveal the tragic fact that, later in the 70s, Dunstan’s second wife, the intelligent and glamorous Malaysian journalist Adele Koh, had received a terminal cancer diagnosis.

The force of Dunstan’s charisma and charm was that he brought almost everyone along with him for a seriously wild ride.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout