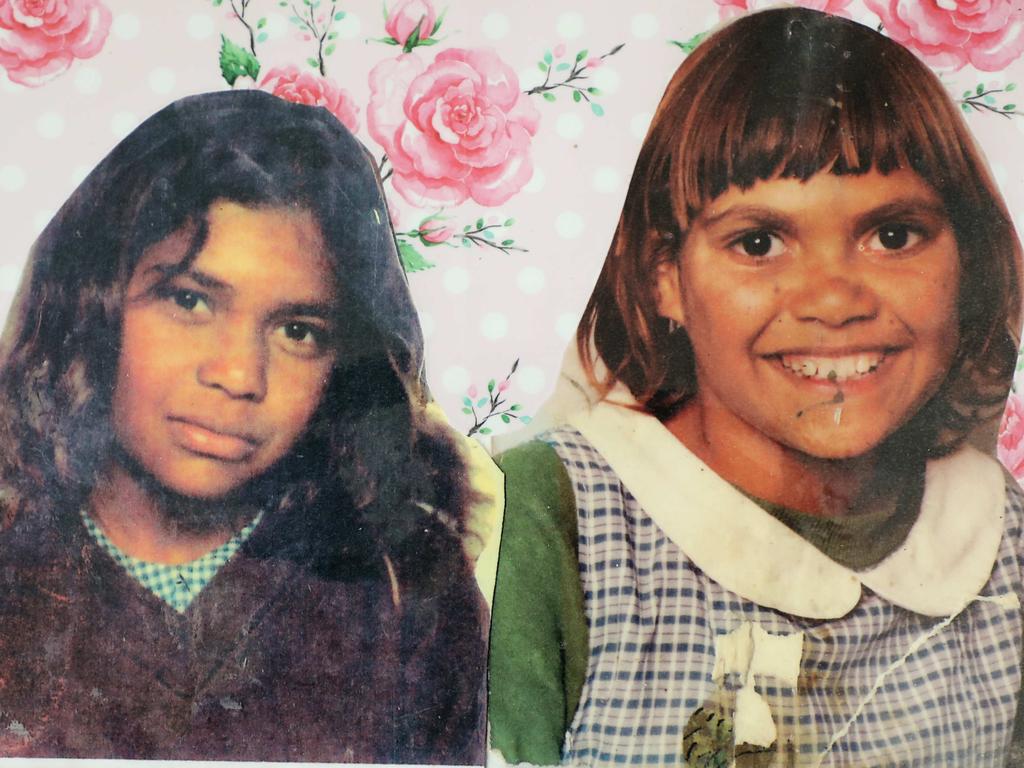

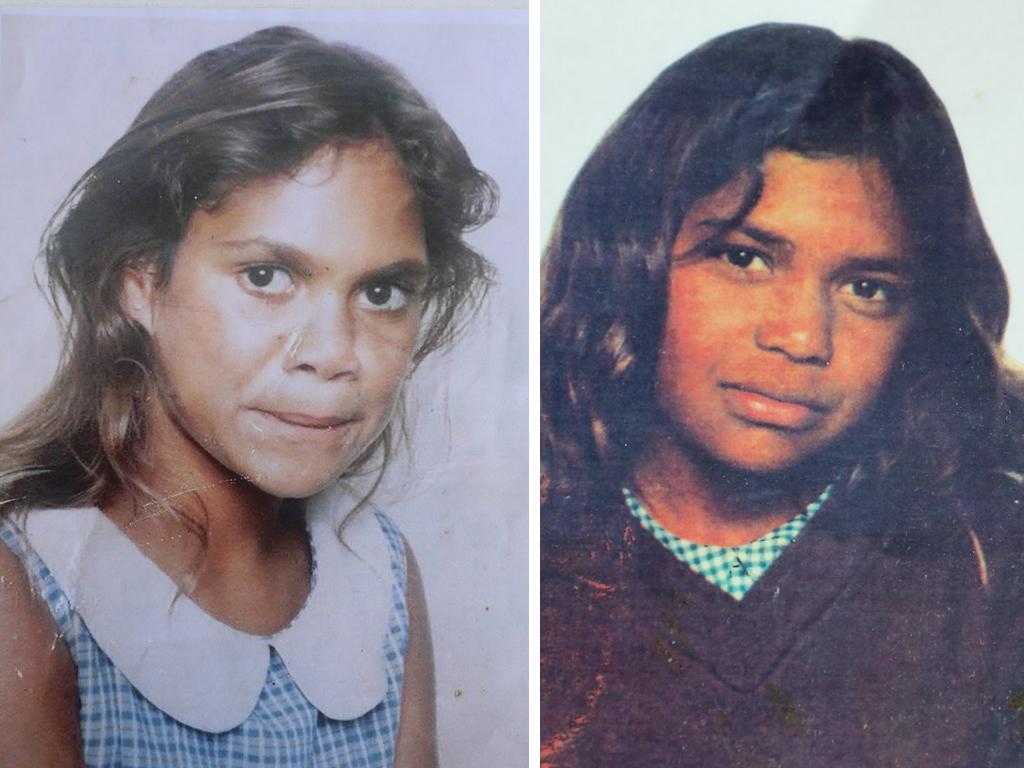

Grieving families hope coroner will offer answers about deaths of Cindy and Mona-Lisa Smith

More than 36 years after two Indigenous girls’ bodies were found in NSW’s outback, state coroner Teresa O’Sullivan will deliver her findings into the teenagers’ horrific deaths.

More than 36 years after the bodies of two Indigenous girls were found on a lonely stretch of highway in NSW’s outback, state coroner Teresa O’Sullivan on Tuesday will deliver her findings into the teenagers’ horrific deaths.

Nobody has been held accountable for the fatalities, and National Justice Project lawyers acting for the victims’ still-grieving relatives, said the inquest findings would be “historically significant’’.

In a statement, the NJP said the girls’ families hoped the coroner would “reveal the truth of what happened to their beloved children … after years of searching for answers’’.

Ms O’Sullivan’s findings will be handed down in the Bourke Court House – the same court where the man accused of killing Jacinta Rose Smith, 15, and Mona-Lisa Smith, 16, in a devastating road crash, and of molesting Jacinta’s dead body, was acquitted in 1990.

This verdict, from an all-white jury, caused uproar in the remote town.

Fiona Smith, sister of Mona-Lisa, told The Australian: “It’s been a long journey, a long battle with no ending.’’

She said she felt “a bit daunted” about what Tuesday would bring.

The coroner’s findings are likely to focus on the initial police investigation into the teenagers’ deaths, which was slammed as “a nightmare”, “shoddy” and “unprofessional’’ by former police investigators who testified at the inquest.

The proceedings were held in November and December and, in startling evidence, a former police accident expert said that when he travelled to Bourke to investigate the double fatality, he was told by a local police inspector to “hop back in your car and piss off back to Sydney’’.

Ms O’Sullivan may also make findings on whether racial bias played a role in the case, and whether the Smith girls’ families were treated differently by police and prosecutors because they are Indigenous.

In December 1987, Jacinta Smith, a Wangkumara girl known as Cindy, and her cousin, Mona-Lisa Smith, a Murrawarri and Kunja girl, died hours after they accepted a lift from Alexander Ian Grant, a 40-year-old white excavator driver.

Shocked farm workers found Grant drunk and unharmed with the deceased teenagers at the devastating crash site outside Bourke. His arm was slung across the exposed chest of Cindy, whose clothing had been interfered with.

Grant was charged with indecently interfering with Cindy’s corpse and culpable driving causing the deaths of both girls. He was acquitted at his 1990 trial after his lawyers argued Mona was driving Grant’s ute when it crashed.

The charge of sexual interference with Cindy’s body had been withdrawn by prosecutors because of a technicality, without the family’s knowledge.

Detective Inspector Paul Quigg, who reviewed the police brief of evidence, told the inquest “a manslaughter charge would have been an appropriate charge to be laid’’ against Grant.

Inspector Quigg also concluded “there was sufficient evidence to proceed with that particular indictment (the interfere with corpse charge) at trial’’.

In a harrowing impact statement, Cindy’s mother, Dawn Smith, now 81, told the inquest she found it “unbelievable” this charge was dropped, calling Grant’s alleged actions with Cindy’s body “evil” and “disgusting”.

Ms Smith described how, after the trial, she chased the acquitted Grant to the local police station.

“I felt so hopeless and defeated,” her statement said.

In her closing submission, counsel assisting the coroner, Peggy Dwyer, recommended that Grant’s exoneration be challenged. Dr Dwyer said: “The evidence points in one way – to Mr Grant being the driver of the vehicle.’’

Dr Dwyer said Grant’s “lie” – that Mona was driving the ute when it crashed – “has been allowed to sit and fester for decades now. And the perpetration of that lie ends, in my respectful submission, with this inquest”.

Inspector Quigg listed “major flaws” in the initial police investigation, including failure to seize Grant’s ute; “inadequate” forensic testing of evidence; failure to take statements from the first witnesses at the scene; and failure to investigate the “critical” issue of whether Mona could drive a manual ute.

Grant was acquitted, even though he initially told police he was driving the ute when it crashed. He also admitted lying to police, and died in 2017, having never spent a day in jail over the girls’ deaths.

The coroner heard from former Bourke detective Peter John Ehsman, who led the initial police investigation and admitted he took at face value Grant’s claim Mona was driving his ute when it crashed. “I didn’t have any doubts, no,’’ he said. “Grant told me one of the girls wanted to drive.’’

Mr Ehsman said he was unaware Grant originally admitted he drove the crashed vehicle. If he had known, his investigation would have been different, he said.

Mona’s mother, June Smith, told The Australian that when she testified at the inquest “I got a lot of things off my chest, even though it hurts”.

Her song, My Heart is Broken in Two, was played to the courtroom and reduced many people to tears. Ms Smith said the NJP’s efforts to obtain recognition for Cindy and Mona, coupled with the inquest, had “made me feel really appreciated, and that everybody cares”.