Gender clinic wins appeal over puberty blockers

A ruling against UK’s specialist gender clinic for children is set aside, with an appeal court rebuking judges for straying into consent decisions that should be left to clinicians.

An internationally significant ruling against England’s specialist gender clinic for children has been set aside, with an appeal court rebuking the judges for straying into informed consent decisions that should be left to clinicians.

On Friday, the English Court of Appeal said last December’s landmark verdict in favour of Keira Bell, 24, a regretful former patient of the Tavistock youth gender clinic, came close to imposing on clinicians “a checklist or script” to use when approving treatment with puberty blocker drugs.

The Tavistock clinic welcomed the judgment, saying “it upholds established legal principles which respect the ability of our clinicians to engage actively and thoughtfully with our patients in decisions about their care and futures”.

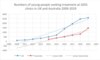

The clinic had halted new referrals, Sweden’s Karolinska Institute clinic stopped offering transgender hormonal treatments as routine six months later, and in July the fast-growing clinic at Perth Children’s Hospital was put under review, reflecting an international trend towards more caution.

Commentators believe the increased scrutiny and debate about gender clinics around the world is unlikely to end with the Tavistock’s successful appeal.

“The Court of Appeal did not disagree with the lower court about whether children under 16 have the capacity to give an informed consent to puberty blockers,” said University of Queensland legal academic Patrick Parkinson, who advised Ms Bell’s lawyers on Australia’s gender dysphoria cases.

“Rather, (the Court of Appeal) said, for technical legal reasons, that the lower court should not have sought to resolve the competing views (about gender dysphoria treatment) within the medical profession.”

The Court of Appeal held that in judicial review, the kind of action brought by Ms Bell, judges should not make controversial findings on untested evidence about whether puberty blockers were experimental or a one-way path to more medicalisation.

Unable to show any illegality, the Bell case had invited a judicial challenge to the Tavistock’s gender dysphoria treatment policy, which was the province of the UK NHS, the medical profession and government, the Court of Appeal said.

The appeal judges said the lower court’s special instructions on how to test the informed consent of minors seeking to block their puberty amounted to an “improper restriction” of the common law “Gillick competence” rule, which leaves this assessment to clinicians. The Gillick competence test is also applied by Australian gender clinics.

Video: Did the appeal judges get it right?

UK family law barrister Sarah Phillimore said “this was not (an appeal) decision about the rights and wrongs of puberty blockers; it was a decision about the limitations of a judicial review.”

She hoped the more open debate about child welfare generated by the Tavistock case would continue, and dispel what she said had been a “dangerous climate of fear, where necessary discussion is shut down as ‘transphobia’.”

She and Professor Parkinson both stressed the Court of Appeal’s clear warning to clinicians to “take great care” before recommending treatment with puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones, and to make sure young patients seeking medical interventions had the benefit of the latest research on the pros and cons.

“(The appeal court) warned that doctors’ judgments about a child’s capacity to give a properly informed consent may be subject to scrutiny by courts, after the event, in civil litigation (such as a medical negligence claim),” Professor Parkinson said.

Psychiatrist Roberto D’Angelo, president of the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine, which is critical of the low-quality evidence base for “gender affirming” hormonal and surgical treatment, said the appeal ruling meant “the clinical and legal responsibility lies squarely in the laps of the clinicians administering these treatments”.

“When more individuals who regret their transition, like Keira Bell, come forward, the clinicians who authorised those treatments will be responsible and hence at risk of litigation,” Dr D’Angelo said.

“The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists’ new position statement on gender dysphoria highlights the medico-legal issues and the need for clinicians to obtain fully informed consent.”

Professor Parkinson said the importance of the gender medicine controversy and the “depth of disagreement” between the two senior panels of judges on the lower and the appeal court suggested the UK’s final court, the Supreme Court, might agree to settle the case.

On Saturday, Ms Bell’s legal team said they would seek leave to appeal. Ms Bell said the Tavistock had become “politicised”.

“A global conversation has begun and has been shaped by this case,” she said. “It has shone a light into the dark corners of a medical scandal that is harming children and harmed me. There is more to be done.

“It is a fantasy, and deeply concerning, that any doctor could believe a 10-year-old could consent to the loss of their fertility.”

Sterilisation is among the potential risks of transgender hormonal treatment.

The gender clinic watchdog group Transgender Trend, which intervened in the case, criticised the Court of Appeal for lending its authority to what it said were dubious claims by the Tavistock on the “time to think” rationale for puberty blocking, and the true proportion of patients who went on to cross-sex hormones.

Comment was sought from Australia’s “gender affirming” clinicians lobby AusPATH and the high-profile gender clinic at the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne.