Why is the government afraid, unwilling or unable to send a warship to Red Sea when our allies ask?

It signals to the world that Australia is no longer the reliable contributor to global security, the loyal ally or the consistent defender of the so-called rules-based order it once claimed to be. Instead, this likely decision reveals a timid and insular government, afraid, unwilling or unable to send a single – yes, that’s right – a single warship to the world’s most pressing maritime hot zone.

It goes against the grain of Australia’s proud history of making modest but symbolically important contributions to multinational deployments on matters clearly in Australia’s national interest.

And what, right now, could be more in Australia’s interests than ensuring the security of the vital sea lanes on the Red Sea, where more than 12 per cent of the world’s trade passes through, including many billions of dollars of Australian imports and exports?

Exactly why Australia would refuse such a request remains shrouded in mystery because this secretive government refuses to publicly explain its thinking beyond vague generalities about giving priority to our immediate region in its naval deployments.

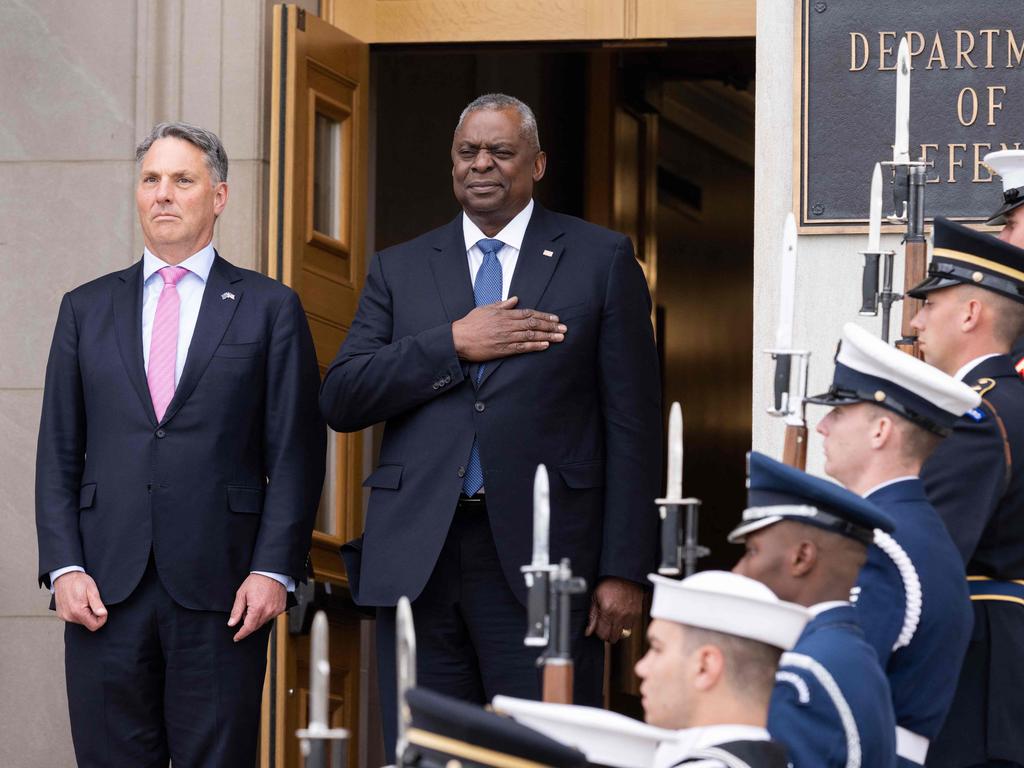

The government is set to formally announce on Wednesday that it won’t send a warship, but it was waiting first to participate in a virtual joint conference with US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin and several other countries before making a final decision.

It has tried to justify its expected decision to refuse the initial US request for a warship by suggesting it wasn’t an urgent request from Washington because it came via the US Navy and therefore didn’t require a timely answer.

Mr Austin clearly disagrees, announcing on Tuesday a 10-country naval taskforce called Operation Prosperity Guardian to protect commercial shipping in the Red Sea from fast-growing missile and drone attacks by Iran-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen.

Mr Austin says the Red Sea crisis “threatens the free flow of commerce, endangers innocent mariners, and violates international law”, and “countries that seek to uphold the foundational principle of freedom of navigation must come together to tackle the challenge posed by this non-state actor”.

Sorry, Mr Austin, but Australia is no longer one of those countries. Never mind the fact like-minded nations such as the UK, Canada, France, Italy, Spain and Norway have joined the taskforce. In the week when critical legislation enabling AUKUS passed in the US congress, Australia is the only AUKUS member to refuse requests to send a ship to the Red Sea.

The decision is all the more bizarre given the Australian Navy has vast experience in the region, having deployed warships to the Middle East almost continuously from the early 1990s to late 2020.

These have operated across the Persian Gulf, Gulf of Oman, Western Indian Ocean, Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea.

In the absence of available facts, it is no surprise rumours are sweeping Canberra that the government could not actually deploy a single warship at short notice over the Christmas period.

Did we not have any of the eight Anzac frigates or three air warfare destroyers ready to go? Did we not have a full crew ready and available for deployment? Is it too hard to cancel Christmas leave or do we have a navy that can’t go to war during public holidays?

Is it because the Red Sea is a “hot zone”, where an Australian warship might have to fire a shot in anger or be fired upon? Is no Australian ship equipped to race to a conflict zone at short notice?

All of these questions are hanging in the air because the government refuses to address them directly. The stated reason for refusing the US request for a warship was that the navy is giving priority to Australia’s immediate region. Well, yes, but that regional focus doesn’t vanish just because one ship is deployed further afield.

The US was not asking for a fleet, it was asking for a single ship to operate in an area where the navy has proven expertise.

The reason all of these questions are being asked is that confidence in the government’s ability to manage the navy is at rock bottom. The same government that says we face the most dire strategic circumstances for 50 years has given no extra money for defence and can’t even make decisions on the future structure of the navy’s surface fleet, having deliberated on it now for more than eight months.

The consequence of this policy slumber is that Australia’s military clout is shrinking and its ability to contribute to vital global issues is fading.

It means Australian sailors will be watching Netflix at home this summer rather than trying to protect vital Australian trade routes from terror attacks.

The Albanese government’s all-but-certain decision to refuse a US Navy request to send a warship to the Red Sea is an embarrassment for Australia.