Social media told to pull ‘black ops’ posts

The Australian government has demanded statements posted online by the Indonesian covert ‘influence’ operation against West Papuan independence be taken down.

The Australian government has demanded social media platforms take down inflammatory and potentially damaging statements posted online by the Indonesian covert “influence” operation against West Papuan independence exposed by The Weekend Australian.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade acted after new revelations that Indonesia’s “black ops” campaign is using images of an Australian diplomat, Dave Peebles, allegedly stating: “Australia affirms not supporting the Free Papua Movement.”

DFAT would not confirm whether Mr Peebles used those words, but The Australian understands the department has asked Facebook, Instagram and Twitter to remove the unauthorised content from their platforms.

The Indonesian attempt to involve an Australian diplomat in its disinformation campaign threatens the delicate and already strained balancing act Canberra maintains with Jakarta over West Papua.

The Australian government does not want to become embroiled in the West Papua issue — on either side.

Tensions in the province have risen dramatically after the announcement last week of a West Papuan “provisional government” under exiled leader Benny Wenda.

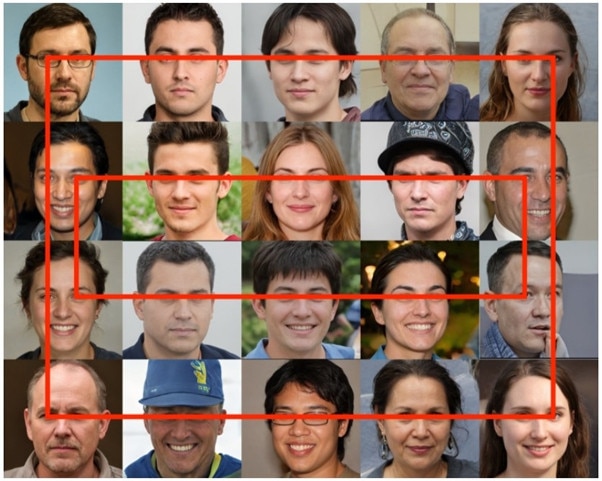

The Weekend Australian revealed the Indonesian government is behind a campaign using multiple fake accounts on social media and employing computer-generated “deepfake” profile images to avoid detection. One account purported to belong to an Australian journalist, Jasmine Eloise — who did not exist.

An Indonesian company, InsightID, spent US$300,000 ($403,926) on advertisements on social media, driving more than half a million Facebook and Instagram users towards fake news sites peddling false information about West Papua and smearing critics, including prominent Australian lawyer Jennifer Robinson.

The Jakarta-backed “influence campaign” pushes a narrative that Australia opposes West Papuan independence, a claim that — unusually for these disinformation operations — is largely true.

Under the Lombok Treaty, both Australia and Indonesia have agreed not to support activities that could constitute a threat to the stability, sovereignty or territorial integrity of the other party — including separatism.

But the existence of a number of Papuan pro-independence activists and groups in Australia continues to be a thorn in the side of the bilateral relationship.

Indonesian human rights lawyer Veronica Koman, who is taking refuge in Australia, is one of the main targets of Jakarta’s shadow “influence campaign”.

Ms Koman has no doubt the Indonesian government is behind the campaign. She has paid a heavy price for her support of the West Papuan independence movement, now forced to live in exile and endure regular rape and death threats.

“Just today I got another threat,” Ms Koman told The Australian last week. “He said, ‘Do you want me to shoot you in the head?’ It is all because of the black campaign to make me look evil and destroy my credibility.”

But her activism from inside Australia is a source of deep and continuing resentment in Jakarta.

Last week the supreme commander of the Indonesian National Armed Forces, Marshal Hadi Tjahjanto, said the threat of separatism in cyberspace had begun to threaten the unity of the nation and was more dangerous than the armed conflict. He singled out Ms Koman, attacking her for “deliberately spreading the issue of separatism in English on social media to get international support”.

The Indonesian government and military are extremely worried about international public opinion on West Papua, said Andreas Harsono, the Indonesian researcher of Human Rights Watch.

Mr Harsono is in no doubt who is behind the latest propaganda war.

“This is a very sophisticated operation,” he said. “Of course the Indonesian government is behind it – but the Government has many bodies.”

The Indonesian government has been conducting disinformation campaigns for decades and has not always been so coy about it, he said.

Mr Harsono recalled a conversation he had with one of Indonesia’s most powerful figures, Luhut Pandjaitan — a retired four-star general, minister and confidant to President Joko Widodo — after Human Rights Watch had analysed leaked documents showing the Indonesian military was behind a disinformation campaign.

“What’s wrong with that?” Mr Pandjaitan asked. “The government has the authority to spy on its own citizens.”

Responded to allegations that the Indonesian government was behind the latest influence operation, a spokesman for the Indonesian Foreign Ministry, Teuku Faizasyah, told The Australian: “We are not in a position to respond to allegations that have to be substantiated. Anybody can claim anything. It’s mainly propaganda on the part of the West Papuan independence movement.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout