Indonesian propaganda against West Papua: Meet our Jasmine. Mad. Mysterious. And made up.

A synthetic warrior in a new kind of cyber warfare threatens our relationship with our powerful northern neighbour | TAKE OUR QUIZ

Meet Indonesia’s new weapon in its battle against West Papuan independence.

Jasmine Eloise is an “Australian reporter” who tweets her full-blooded support for Jakarta’s rule over the troubled province.

But Jasmine isn’t a journalist. She’s not even human. Jasmine is a machine-generated image, a synthetic warrior in a new kind of cyber warfare that threatens our relationship with our powerful northern neighbour.

An investigation by The Weekend Australian has confirmed the Indonesian government is behind a secret “black ops” disinformation campaign to influence Australian and international opinion against West Papua’s independence movement and to attack human rights activists in Australia.

The well-funded operation uses multiple fake accounts on social media and employs computer-generated “deepfake” profile images to avoid detection.

The covert campaign targets opponents of Indonesian rule in West Papua, such as prominent Australian barrister Jennifer Robinson, who also represents Julian Assange. It smears her as “slutty” after falsely accusing her of being involved in a sex scandal.

Indonesia’s troll factory has been quietly operating from behind a locked steel gate in a neat, two-storey villa on a tree-lined street in an upmarket part of South Jakarta, The Weekend Australian can reveal.

The building’s tenant, an Indonesian media and marketing company called InsightID, has spent $US300,000 on advertisements on social media, driving more than 500,000 Facebook and Instagram users towards fake news sites peddling false information about West Papua and lashing out at critics.

The Weekend Australian has established that InsightID was commissioned and paid for its services by the Indonesian government.

Another of the campaign’s targets is exiled human rights lawyer Veronica Koman, who lives in Australia and has been subjected to rape and death threats.

“Just today I got another threat,” Koman tells The Weekend Australian. “He said: ‘Do you want me to shoot you in the head?’ It is all because of the black campaign to make me look evil and destroy my credibility.”

The escalating online offensive matches a real one taking place in West Papua, with increasingly violent clashes between separatists and Indonesian troops in recent months amid claims of racism against the region’s ethnic Melanesian population. The decades-long conflict erupted again last year, triggered by an incident in which Indonesian soldiers shouted “monkey” at West Papuan students. At least 30 people were killed in the violence that followed.

Tensions will be further inflamed by this week’s dramatic announcement by separatist umbrella group United Liberation Movement for West Papua of a “provisional government” under exiled leader Benny Wenda.

With the province all but off limits to foreign journalists, social media has become the main source for news about the conflict, with activists such as Koman posting videos of police and military brutality and exposing the uprising to a Western audience.

Koman points out that some of the fake accounts use footage she doesn’t have access to. “It means the footage comes from the other side — the Indonesian military.”

Tweeter doesn’t exist

Last week, Indonesian National Armed Forces supreme commander Marshal Hadi Tjahjanto said the threat of separatism in cyberspace had begun to threaten the unity of the nation and was more dangerous than the armed conflict. Hadi singled out Koman, attacking her for “deliberately spreading the issue of separatism in English on social media to get international support”.

Cue Jasmine Eloise, an “Australian reporter”, who blasts Koman on Twitter as “a pathetic drama queen” suffering from “emotional dysfunction”.

Jasmine is a prolific tweeter from her @jasmineeloise3 Twitter account. But she doesn’t exist.

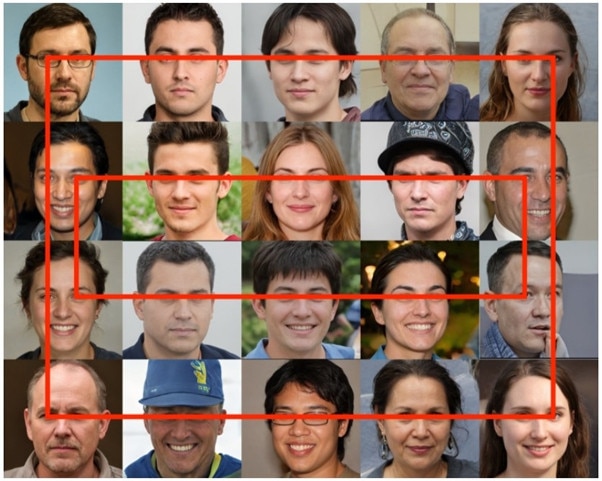

Her image was created by a Generative Adversarial Network, a machine learning program that morphs new human faces from thousands of real-world images. The technique is designed to prevent reverse-image searches identifying pictures that have been lifted from elsewhere.

The GAN images are extraordinarily lifelike, but not always perfect. One giveaway is the position of the eyes, which always remain in the same place in the photo. Some images fail to blend correctly, revealing small glitches, especially with clothing, haircuts and backgrounds.

Hijacking bots

The disinformation campaign was first spotted by Australian cyber sleuth Benjamin Strick, who noticed that even after Indonesia cut internet links to West Papua last year, there was still a barrage of online content ostensibly from the province.

Strick, who works with the Britain-based Bellingcat open-source investigations team, discovered hundreds of “bots” — automated social media accounts — with profiles using photos of K Pop stars and random individuals lifted from the internet.

These bots would hijack hashtags such as #FreeWestPapua, that were used by pro-independence groups, spamming them with positive stories about the “special autonomy” status Indonesia says it has granted the province, and smearing opponents such as Koman as terrorists and criminals.

“This bot network was trying to drown out any activists that were talking about West Papua, and it really skewed the narrative for a lot of people,” Strick says.

That network links back to Indonesian media company InsightID. On its now deleted website the company boasted: “We are employing a sense of perfectionism and even morality to our work. Rules, limitations, and traditions are anathema — everything should be open to questions and re-evaluation.”

InsightID was established in 2018 by three young tech wizards, Pera Malinda Sihite, Abdul Aziz and Fitri Handayani, who studied communication science together at Jakarta’s Bakrie University.

For a few months the fledgling company did marketing for Korean pop music groups, but soon took on a new task. In August 2018, Aziz registered 14 internet domains on one day, with names such as westpapuafreedom.com and westpapuafact.com.

The company placed ads for university students, especially those studying international relations, to work on the project.

“These students have good English, they know social media, and they’ve got a sophisticated knowledge of the world,” Strick explains.

In September 2018, Indonesia’s new cyber troops launched their attack. Some of the company’s Twitter accounts simply switched overnight from spamming fan trivia about K-pop band NCT to attacking West Papuan activists as terrorists.

As Strick observes: “The difference between an information operation and marketing is the intention to deceive audiences for political purposes, but the core skills required are the same.”

InsightID spent$US300,000 on Facebook ads paid for primarily in Indonesian rupiah. But the whole campaign would have cost much more. “Every post on YouTube, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter has a unique video or meme attached to it, so they’ve also hired graphic designers to make these,” Strick says.

The advertisements also target Facebook users in The Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, Britain and the US, with some posts written in Dutch and German.

Facebook’s cyber security team recently removed 69 Facebook accounts and 34 Instagram accounts used in the campaign to drive users to off-platform websites opposed to West Papuan independence. About 530,000 people followed one or more of these accounts.

Designed to intimidate

Among the websites is one that smears Britain-based Australian lawyer Robinson as “slutty” and, without evidence, claims her alleged relationship with a British political staffer shows Free West Papua supporters will use “any means to reach their goal even with sexual means”. “I think it is important to understand how things work either morally or immorally in the world,” says the anonymous author.

Robinson has been providing legal advice to the newly-declared provisional government. “It’s designed to intimidate, but I think it’s pathetic that they’re resorting to this kind of tactic,” she says. “I think it’s a sign of desperation.”

Since Strick’s investigation, InsightID appears to have abandoned its Jakarta headquarters. The street number on the gate post, 21A, was changed to 21B in a crude bid to obscure the address. The company has disappeared from public view and tried to wipe its digital footprints. So have its founders, who failed to respond to this newspaper’s approaches.

But the dirty tricks campaign continues unabated.

When the puppet-masters realised they’d been sprung, they switched to the GAN-created photo identities in a bid to avoid detection. They also began creating accounts purportedly belonging to journalists — such as synthetic human Eloise — in an attempt to build credibility and authority for their message.

“We’re seeing more and more of these social media profiles that purport to be journalists, particularly on Twitter,” says Elise Thomas, from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, who has tracked the West Papua campaigns. “My suspicion is that it’s aimed at engendering more trust from other journalists.

“In places like West Papua, where it’s difficult to get independent reporting, these campaigns can have a significant impact on how a conflict is perceived. From that perspective, they can be very dangerous.”

Like Russian President Vladimir Putin’s notorious Internet Research Agency troll factory in St Petersburg, the aim is not necessarily to convince, but rather to sow doubt and confusion.

As the hashtag #PapuanLivesMatter went viral this year, inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement in the US, so did the number of fake accounts hitting the tag and directing traffic to anti-independence websites.

‘Guterres’ quoted

Another separate but overlapping influence campaign, Tell The Truth NZ, specifically targets New Zealanders and also has direct links to the Indonesian government. This second network includes two other social media brands, the Wawawa Journal and Noken Insight.

The sites and social media platforms publish false or misleading claims about West Papua, including fake documents quoting UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres as saying that “criminal and separatist groups are constantly making hoaxes and anarchist demonstrations and acts of violence”.

All are run by or connected to Muhamad Rosyid Jazuli, who works with the Jenggala Institute for Strategic Studies, a political body created by former Indonesian vice-president Jusuf Kalla, which actively campaigns for Indonesian President Joko Widodo.

Mr Jazuli did not respond to questions from The Weekend Australian.

On Friday night a spokesman for the Indonesian Foreign Ministry, Teuku Faizasyah, said “we are not in a position to respond to allegations that have to be substantiated”. “Something needs to be proved,” he said. “Anybody can claim anything. It’s mainly propaganda on the part of the West Papuan independence movement.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout