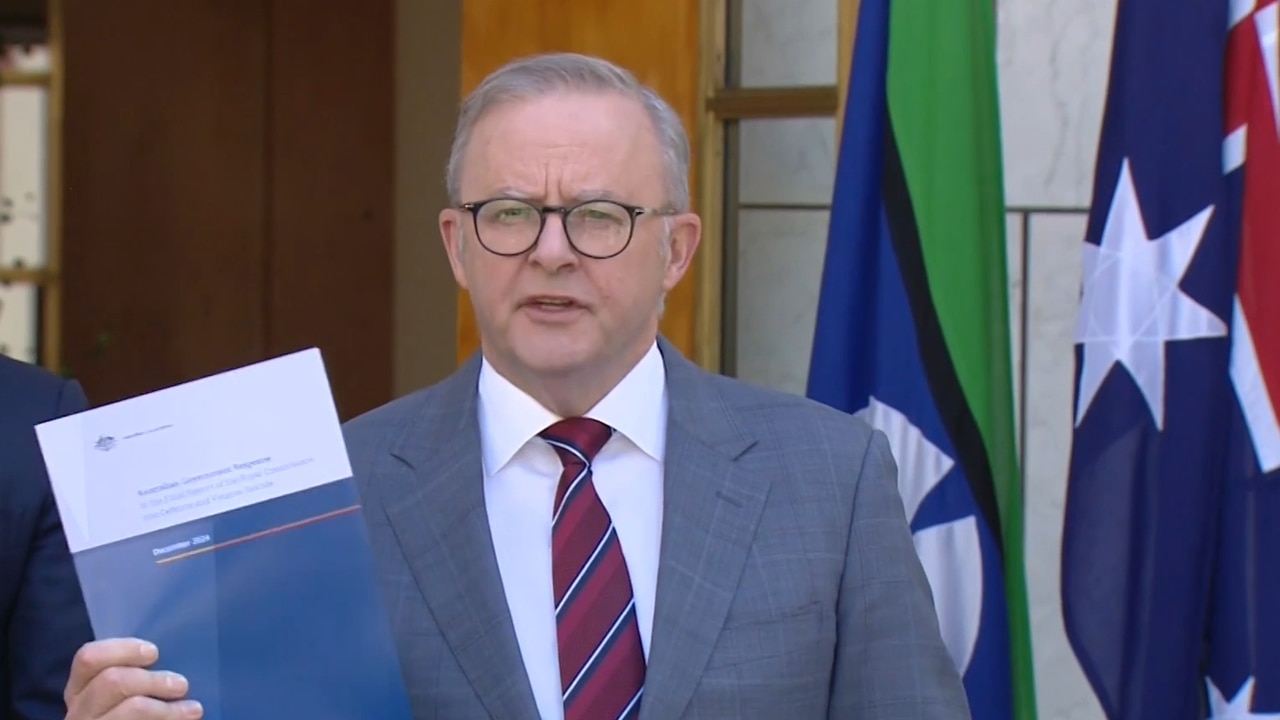

Anthony Albanese has vowed the most comprehensive reform ever to Defence culture and veterans’ care to stop ex-servicemen and women from taking their own lives. But how far is he prepared to go to deliver on the promise?

Defence and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs have proven remarkably resistant to change, and the government is silent on how much is it prepared to spend fixing a system that everyone agrees is broken.

Veterans have heard these sorts of commitments before, but little has changed despite more than 50 inquiries over the past two decades.

The seven-volume report of the Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide, led by Nick Kaldas, is the most comprehensive yet.

After piling political pressure on the Morrison government to initiate the three-year royal commission, Labor is the undisputed owner of the Kaldas report and will be judged on how successful it is in implementing its recommendations.

But the reasons veterans are 20 times more likely to die by suicide than on active duty are devilishly complex, and making a real difference will be a long and difficult task.

The government will create a new bureaucratic body, the Defence and Veterans’ Services Commission, to lead the rollout of “enduring and systemic” reform.

But there is no word on what powers it will have to force change on the Defence establishment and the perennially underperforming DVA.

A promised crackdown on sexual abuse in the Australian Defence Force is welcome, and will include a new formal inquiry into sexual violence in the military. But how will this be any different to past inquiries that have examined the very same problem?

New policies to assess officers’ “emotional intelligence” and link promotion to cultural and wellbeing targets are also good in theory, but face being gamed by individuals and misappropriated by politically correct culture warriors.

Those looking for clues to the government’s real level of commitment to lasting change will find cause for concern in its equivocal response to some of the royal commission’s less prominent recommendations.

It has merely “noted”, for example, the inquiry’s call for the fees paid for veterans’ health care to be aligned with those for National Disability Insurance Scheme recipients.

The government acknowledges that the gap between DVA and NDIS fee schedules “can have a negative impact on access for veterans”. But it has kicked the can down the road, saying it will consider the issue in a wider examination of healthcare pricing.

Likewise, its “in-principle” agreement with the royal commission’s recommendation for the establishment of a veterans’ brain injury program.

The response glosses over the hot-button issue of blast-induced brain trauma, which is caused by repeated exposure to explosions in training or combat.

The royal commission called for proactive monitoring and assessment of ADF members’ blast exposure, which would be vital to tracking the extent of the problem but could constrain the type of training that’s undertaken and open up a compensation can of worms.

The government failed to specifically address the recommendation, saying instead that Defence would leverage off research carried out by the US and other Five Eyes nations.

Already, nearly $500m has been ploughed into the DVA, following the royal commission’s interim report, to hire 500 claims-processing staff and update its ageing IT systems. Much more will be needed to deliver on the government’s new veteran-centred plan.

But the key ingredient in tackling the problem will be the government’s own political will to ram through its new reform agenda and hold Defence and DVA accountable for their treatment of those rare Australians who serve in the nation’s uniform. On that, the jury is still out.