Coroner questions gun licence system that relies on applicant’s honesty about mental health

Just days after his 20th birthday, Robbie Lawrence unlocked his double-barrel 12-gauge shotgun from his father’s gun safe, drove to a remote bush track in regional Victoria, and killed himself.

Just days after his 20th birthday, Robbie Lawrence unlocked his double-barrel 12-gauge shotgun from his father’s gun safe, drove to a remote bush track in regional Victoria, and killed himself.

With the help of his dad Robert, Robbie had applied for a junior firearm licence in 2013, when he was 16, and the pair went shooting together at the local range.

When he applied to Victoria Police’s Licensing and Regulation Division for the permit, and the adult Category A & B firearm licence in September 2014, Robbie declared he had no medical conditions – including psychiatric, depression, stress or emotional problems – that might affect his suitability to own a gun.

But according to an investigation by Victorian coroner Paresa Antoniadis Spanos – the findings of which were published in 2020 but have been unreported until now – the truth was much more complicated than that.

Target on Guns

Extremists, crims, AVOs on guns register

A $250m national firearms register will have access to criminal records and family violence orders alongside details of guns and firearm licence holders.

Firearms register win, as FBI nabs cop killers’ US contact

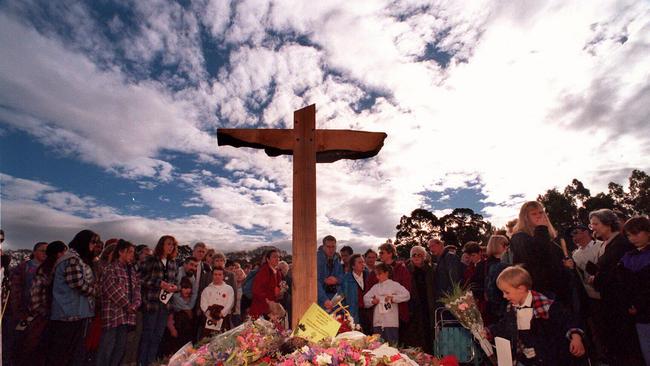

Twenty-seven years after it was first agreed following the Port Arthur massacre, Australia’s leaders sign a historic deal to introduce a national gun registry.

Nation’s leaders urged to do deal on gun register

Police and gun safety advocates urge premiers, PM to ‘show some fortitude’ on firearms ahead of the anniversary of the Wieambilla police murders.

‘Red-flag cop-haters, sovereign citizens’ on firearm register

A national firearm register should include intelligence about licensed gun-owners who have been identified on social media as ‘police-haters’ or sovereign citizens.

Fight over cash derails register

The national guns register has hit an 11th-hour roadblock with a blow-up between state and federal treasurers derailing plans to finalise a funding deal.

Delays give high-risk suspects 41-day start

No money, competing priorities: Victoria Police delays give high-risk suspects 41 days grace period before firearm prohibition orders are served.

Firearms register ‘now within range’

Gun safety advocates say Australia’s state, territory, and federal governments have ‘never been closer’ to a deal on a national firearm register, 27 years after the Port Arthur massacre that first prompted calls for the database.

Young shooters aim for sporting success

Sport for some kids involves a ball or a racquet, but 12-year-old Quinn Coates-Marnane much prefers a pistol. The Cairns schoolboy is one of a growing number of children learning how to shoot competitively.

‘Ridiculous’: Police slam failure to act on guns register

An Australian-owned and operated company built New Zealand’s new national firearms database, prompting police advocates to ask why the same can’t be used domestically.

Victoria cries poor on guns, asks Canberra for help

Victoria has joined smaller jurisdictions asking Canberra for financial assistance to upgrade old state firearms registers to make them compatible with a real-time digital national gun database.

Aussie-made arms register controls guns abroad – why not here?

A low-cost simple-to-use system known as ArmsTracker is operational or being installed in countries across the globe. But its creators say it wouldn’t suit Australia because ‘they wouldn’t trust anything less than $2m’.

$30m slug to sign up to firearms registry

Smaller states and territories could be slugged with a bill of $30m each to join a national firearms register and are increasing pressure on the federal government to pay for the new digital guns database.

Pressure on state to ban replica ‘gel blasters’

Gun control advocates urge Queensland to follow the rest of Australia and ban gel blasters instead of labelling them toys.

20 years’ jail for firing this ‘toy’? It’s ludicrous, blasts judge

In every other jurisdiction except Queensland you need a gun licence to wield this recreational weapon. Has the rest of the country got it wrong?

States resist health check for licences

Every state and territory except WA is resisting calls from coroners and advocates to introduce mandatory mental health checks before gun licences are granted.

Grieving mother’s lament: Why did police let my son have a gun?

Just days after his 20th birthday, Robbie Lawrence unlocked his double-barrel 12-gauge shotgun from his father’s gun safe, drove to a remote bush track in regional Victoria, and killed himself.

Legal guns near four million in Australia

The number of registered guns in Australia approaches four million for the first time, but ownership rates remain low, with a 48 per cent decline since the National Firearm Agreement in 1996.

The forgotten victims of legal guns

Children, grandchildren and partners are the main victims of homicides carried out by licensed shooters, as lawful gun owners turn their registered weapons on those to whom they are closest.

Coroners warn on shooting range suicides

Most of the nation’s shooting ranges are not required to install bulletproof barriers or lifesaving tethers for guns used by unlicensed shooters, despite coroner warnings after the suicides of at least 11 people.

Shockwaves after daughter lures her dad to a violent death

It’s been 13 years since Di Bonarius’s sister shot their beloved father dead after stealing a gun from a pistol club, but the traumatic aftershocks of the violence are still shaking her family.

Inquest costs met for cops’ families

The families of the two murdered officers will have union-funded lawyers to represent them at the inquest, as one family expresses concern about some actions of Queensland police.

Christian extremist terror hit not enough to deliver gun register

Nearly a year after constables Matthew Arnold and Rachel McCrow and good Samaritan Alan Dare were gunned down at Wieambilla, bureaucratic inertia and a fight over funding has stalled the process.

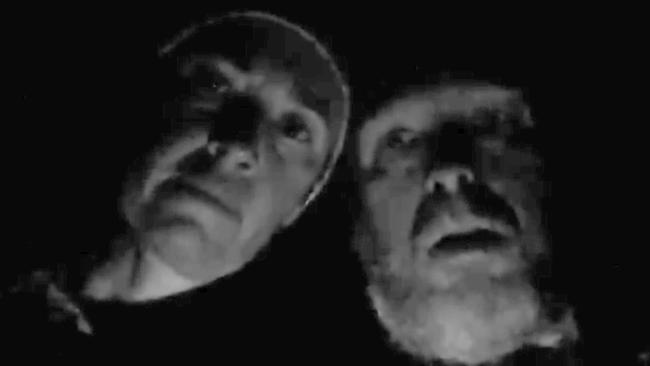

Young cop’s execution caught on body cam

Sniper’s lairs, battery-powered security cameras, and the cold-blooded execution of a young constable captured by her own body-worn camera: what really happened during the bloody Wieambilla ambush.

New laws were a killshot for Ella Valla station. Then Andrew Forrest swooped

For years, tourists would come to Shane Aylmore’s remote cattle property in WA, paying huge sums to fire enormous long-range weapons into the outback. In just one night, it was game over.

Gun, data reforms ‘would save cops’ lives’

‘Real time’ information would enable police to do a proper risk assessment before entering a property.

Outdated registry ‘is a threat to police’

Queensland’s firearms registry is still not fit-for-purpose and is putting police officers and the general public at risk, nearly three years after a warning from the auditor-general.

Up to 130,000 WA guns off the street

WA will become the first Australian jurisdiction to limit how many firearms a shooter can legally own, as the Labor government wants to slash the number of legal guns by about one-third.

Federation fail: Patchwork of laws keep sniper rifles on our streets

High-powered .50 cal guns banned for being too dangerous by some states are legal over the border, as states and territories fail to harmonise gun laws or agree to a national gun registry.

His mum Julie Lawrence, who he lived with in Waurn Ponds after his parents’ separation in 2005, told Ms Spanos that Robbie had a medical history of congenital blindness in his right eye, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, depression, Tourette’s syndrome, obsessive compulsive disorder, and borderline Asperger’s syndrome.

Most concerningly, in March 2015, Robbie started talking about suicide, after being bullied and abused at work as a mechanic’s apprentice. He made a noose, though didn’t use it.

Ms Lawrence complained to the state’s apprenticeship board, and had Robbie reviewed by a psychiatrist called Dr Eseta Akers on January 19, 2016.

He told Dr Akers he was obsessed with war, guns, lighters, and bayonets, and had unresolved issues with his father.

“Robbie threatened to hurt himself and others when relationships became difficult and threatened to use his gun on himself,” the coronial findings said. “However, when Robbie felt secure he denied having any such intent.”

Dr Akers found Robbie had a “chronic moderate risk of harm to himself and others in the context of emotional dysregulation and impulsivity”, and wrote in her report dated January 20, 2016, that Robbie’s access to guns was “concerning”.

Robbie’s mother, who had never been comfortable with him having a gun licence, was very worried about him.

Robbie was referred to other mental health care treatment, and Dr Akers discussed Robbie’s access to firearms with the clinical director of the Barwon Health Jigsaw Youth Mental Health service. The two doctors decided that the “risks of intervening outweighed other potential risks, and the recommendation was to not make a notification to Victoria Police at that time,” but the decision would be reviewed if Robbie’s health deteriorated.

If the police’s weapons division is warned a gun-owner is suicidal, the person’s licence is urgently suspended, and police make sure they don’t have access to firearms.

In August 2016, Robbie and his girlfriend broke up after she moved interstate. He was worried about money, lost confidence, and seemed to struggle with everyday life.

And in October of that year, he told his mother he was going to the firing range with his dad. Mr Lawrence was busy and told Robbie where he could find the spare keys to his house and the gun safe. Neither of Robbie’s parents, nor his older sister Stephanie, saw him again.

Ms Lawrence reported him missing just before midnight on October 18, 2016. He was found shot dead near his red Holden sedan on October 20.

Robbie’s mother lobbied for years for a coroner to investigate the case, concerned about the state’s weapons licensing system and questioning how someone with a mental illness was able to legally obtain a gun licence.

After reviewing Robbie’s death, Ms Spanos found the system did not proactively assess someone’s suitability to own a gun, and relied instead on an applicant’s honesty.

“The current paradigm for the granting of firearms licences relies too heavily on the applicant being entirely honest and disclosing information against their own interest when they apply for a firearms licence,” she said.

Anyone experiencing a crisis can call the below helplines for support and advice: Lifeline 13 11 14 | Kids Helpline 1800 55 1800 | Beyond Blue 1300 224 636

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout