Class actions to allege modern repeat of Stolen Generation

Hundreds of Indigenous families are joining planned class actions across Australia, alleging racial discrimination by state authorities that took their children into care over the past two decades.

Hundreds of Indigenous families are joining planned class actions across Australia, alleging racial discrimination by state authorities that took their children into care over the past two decades in a repeat of the Stolen Generations.

A pathfinding class action has already been filed in the Federal Court in Queensland, with similar lawsuits being planned in Victoria, NSW, Western Australia and South Australia.

The cases will resurrect some of the history of the Stolen Generations and the findings of the 1997 Bringing Them Home report into the systematic removal of Indigenous children from their families and communities, stretching from colonisation to the 1970s.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are disproportionately represented in state care, with figures earlier this year showing a national average of 58 out of 1000 Indigenous children in the system.

This is compared to a rate of 4.7 per 1000 of non-Indigenous children in state care.

Inquiries in NSW, Queensland, Victoria and South Australia over the past decade have criticised child safety departments over their heavy-handed dealings with Indigenous families and their failure to place the children with extended family or within the Indigenous community.

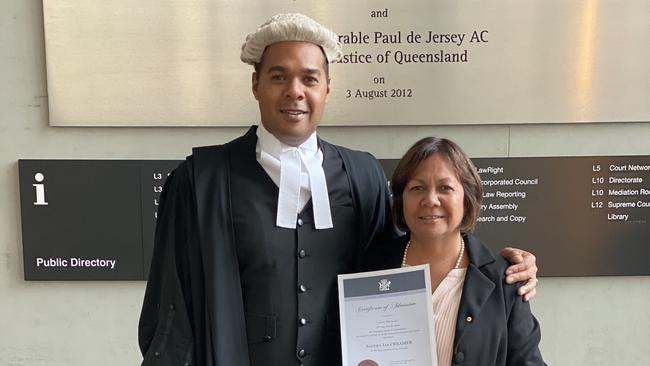

The class actions are being handled by Cairns-based Bottoms English Lawyers and ASX-listed Shine Lawyers and involve Indigenous barrister Joshua Creamer.

In Queensland, the class action was filed in the Federal Court this month after complaints by two Indigenous people, who were removed from their families soon after birth, could not be resolved by the Australian Human Rights Commission.

The class action will focus on what happens after children enter the system, with the central allegation that authorities systematically deprived them of their connection to family, culture and community.

It also alleges a widespread failure by Queensland child safety officers to attempt to later reunite children with their parents, often after they have fulfilled requirements set out by the department.

More than 100 Indigenous people have signed up to the Queensland class action, headed by the two representative claimants, including one man who has also had his three children removed from his care – with thousands more possibly joining the lawsuit.

In documents filed in the Federal Court, the action alleges breaches of the Racial Discrimination Act in relation to children removed from their families and parents who had their children removed.

It also alleges a systematic breach of the Queensland Department of Child Safety’s own legislation and its child “placement principle” which requires officers to exhaust all attempts to place children with other family members or within the Indigenous community before they are handed over to non-Indigenous carers.

Jerry Tucker, special counsel to Bottoms English lawyers, told The Australian there were prospectively thousands of people joining the class action, which will focus on the actions of the child safety authorities once a child is removed.

“We allege that systemic failure to adhere to the principles breaches internationally recognised human rights and has resulted in fractured family units as well as severing connections to culture and community,’’ she said.

“We expect that the evidence will also demonstrate a deeply concerning culture of failing or refusing to reunite or restore family relationships between removed children and their parents, even after the parents have wholly or substantially complied with the department’s stipulated conditions.

“The impact on families is devastating and wide-reaching. It retraumatises First Nations families, many of whom see the department’s conduct as a modern day repeat of the Stolen Generations, or as akin to the so-called Protection Era.”

One of the claimants, Brett Gunning, now 49, was taken into the “custody” of child services a month after his birth in 1974 and placed with a non-Indigenous family who adopted him as a baby. He was separated from his siblings and knew nothing about his Aboriginal family until he was between eight and 10 years of age.

The class action alleges his removal was unlawful and that he was “denied the right to know who his biological family was or what his traditional language, country and culture were”

“The respondent’s actions had the effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment, or exercise of the applicant’s right to enjoy his own culture and to use his own language, contrary to Art 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR),” it states.

Mr Gunning’s three children were also removed from his care.

The Federal Court action claims he later met all the demands of child safety authorities, including completing parenting courses and engaging in counselling, but did not have his children returned.

“Despite the compliance … the respondent did not permit, facilitate, or adequately facilitate family healing between the applicant and his children,” the claim states.

As of June this year there were 5859 Indigenous children in state care out of total of 12,496 children in Queensland. Of those about 2600 were placed with extended family or Indigenous carers.

The Queensland class action seeks compensation, a formal apology, an order for better Indigenous training of child safety workers, and a well-resourced process to help restore families.

A spokesman for the Queensland Department of Child Safety said it was aware of the legal action but that it was inappropriate to comment on it while it was before the courts.

Shine Lawyers special counsel Caitlin Wilson said the firm was planning similar class actions in NSW, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia.

Among the individual cases proposed for the class actions is the removal of a child after her mother asked for financial help to buy formula and was deemed “unable to provide necessities of life”. Another case involves a child who was removed when she had a fall and was taken to hospital by her mother, who had no criminal record or previous contact with child safety workers.

Ms Wilson said the firm would seek compensation for families and that the class actions would help “shine a light” on past practices and drive legislative change.

“The proposed claims relate to the over-representation of Indigenous children in the child protection system, particularly with respect to children placed in out-of-home care, and the various departments’ conduct, which we allege amounts to discrimination and/or negligence,’’ she said.

“When Shine Lawyers began investigating the potential claims, it was evident that the government and those within the child protection system knew about the significant over-representation of Indigenous children in the child protection system given the number of reports and inquiries that have been undertaken over the last 25 years.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout