Yoorrook commission’s version of history will do little to help Indigenous kids now

Culture war does little to keep Indigenous kids out of the child protection and justice systems.

If walking side-by-side with non-Indigenous Victorians was ever part of the Yoorrook Justice Commission’s plan, then the events of this week make it clear this is no longer the case.

In her foreword to a major report into Victoria’s child protection and criminal justice system, Commission chairwoman Eleanor Bourke unleashed a full-frontal assault on the past 200 years of Victorian history. As radical as many of the 46 recommendations released on Monday were, among the most significant aspects of the report were the language and tone in the opening.

Bourke begins: “Since the arrival of Europeans in Victoria in the 1830s, First Peoples have been removed from our families and our country and institutionalised at alarming rates as a result of the colonial systems forced upon us.

“Police and the processes of the criminal law were part of that system with devastating consequences for our people.

“From the early ‘protection’ legislation that allowed the government to control and regulate our lives, we have experienced and continue to experience systemic racism, harm and injustice at the hands of the State. Gross human and cultural rights violations occurred which set the pattern for the future.”

Bourke continues: “Witnesses told Yoorrook how the child protection and criminal justice systems have routinely failed our families and communities. Yoorrook heard of a ‘pipeline’ in which our children are moved from the child protection system into the youth justice system and ultimately into the adult justice system.”

Within the report, the culture war theme continued: “The present-day failures of Victoria’s criminal justice and child protection systems for First Peoples are deeply rooted in the colonial foundations of the State of Victoria. European invasion, and the colonial laws and policies which followed it, were predicated on beliefs of racial superiority. The systemic racism which persists today has its origins in colonial systems and institutions.

“Before European invasion, First Peoples were independent and governed by collective decision-making processes with shared kinship, language and culture.

“They belonged to and were custodians of defined areas of country. First Peoples were self-governing, and wielded economic and political power within their own systems of law, lore, culture, spirituality and ritual.”

There is no disputing that young Indigenous Victorians are over-represented in the child protection and justice systems. The Yoorrook commission reported that at June last year, Aboriginal children, when compared with non-Aboriginal children in Victoria, were 5.7 times as likely to be the subject of a report to child protection services, 8½ times as likely to be found to be in need of protection by child protection services and 21.7 times as likely to be in out-of-home care.

In Victoria at December 31, 2016, there were 1743 Aboriginal children in out-of-home care. At December 31 last year there were 2635, according to evidence given by the state’s Department of Families, Fairness and Housing Victoria.

Nationally last year, 42.8 per cent of children aged 0-17 in out-of-home care were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander – an increase of 2.8 per cent since 2019, according to the Productivity Commission.

Clearly something needs to change to break this tragic cycle and all Victorians, whatever their heritage, have an interest – and those in positions of authority an obligation – to do better.

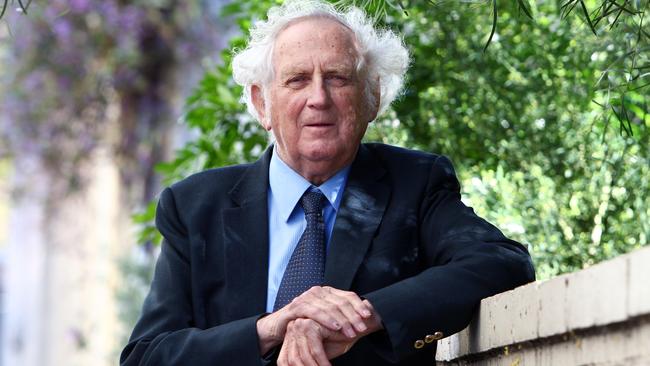

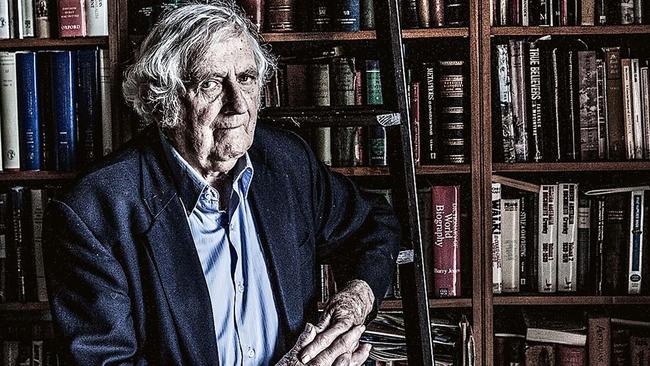

Responding to questions from The Australian’s Rachel Baxendale, eminent historian Geoffrey Blainey challenged the Yoorrook report, saying it was drawing on a “make believe” version of history.

“The idea that Aboriginals practised ‘collective decision making’ comes from Bruce Pascoe and our Prime Minister. Their belief that Aboriginals invented democracy 80,000 years ago is make-believe,” he said. “Traditional Aboriginal society tended to be authoritarian, and far from democratic. My book, The Story of Australia’s People: the Rise and Fall of Ancient Australia, discusses the kind of historical errors which are now embodied in the Yoorrook verdicts.”

Blainey also challenged Yoorrook’s claim that “the systemic racism which persists today has its origins in colonial systems and institutions”.

“There is plenty of evidence that Aboriginal tribes or ‘nations’ thought that they were innately superior to their neighbours,” Blainey told Baxendale.

“Brutal warfare existed between Aboriginal peoples, but it is not even mentioned in this week’s edict. Victoria was not the Garden of Eden before 1788, nor after 1788.”

Given the tone and timing of the Yoorrook Justice Commission’s report, it is not surprising it has bled into the broader debate dominating Australia about the referendum to enshrine an Indigenous voice to federal parliament in the Constitution.

Those leading the campaign for a No vote on October 14 were quick to pounce on the report and its recommendations which, if implemented, would establish completely separate Indigenous child protection and justice systems and even impose Indigenous-focused criteria on the appointment of future chief commissioners of Victoria Police.

Coalition frontbencher Jacinta Nampijinpa Price condemned the Yoorrook report, claiming “lowering expectations for Aboriginal Australians does not help solve the problems that lead to over-representation in the criminal justice and child protection systems”.

Victorian Indigenous leader Ian Hunter said some of the recommendations would result in an “apartheid” system with “one rule for blackfellas and another for everyone else”.

Nyunggai Warren Mundine slammed a recommendation that would require the state’s top cop to have an understanding of the “role of Victoria Police in the dispossession, murder and assimilation of First Peoples”. Mundine said this talked to a “grievance and victim” philosophy underpinning Yoorrook. Mundine told The Australian that while Indigenous Australians were over-represented in prisons, “most of us are not incarcerated; we don’t have problems with the police; we get on with our lives”.

Perhaps sensing the aggressive tone and radical nature of the Yoorrook report could damage the Yes vote, campaigners such as Indigenous leader Marcia Langton and former Liberal Indigenous Australians spokesman Julian Leeser, both voice proponents, argued the issue had “nothing to do with the voice”.

How does firing another shot in a culture war keep Indigenous kids out of child protection and the justice system? For instance, it is difficult to see how imposing a set of Indigenous guidelines on the selection of Victoria’s top cop will keep one Indigenous kid out of jail.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout