Chris Dawson appeal: Babysitter moving in ‘not proof of murder’

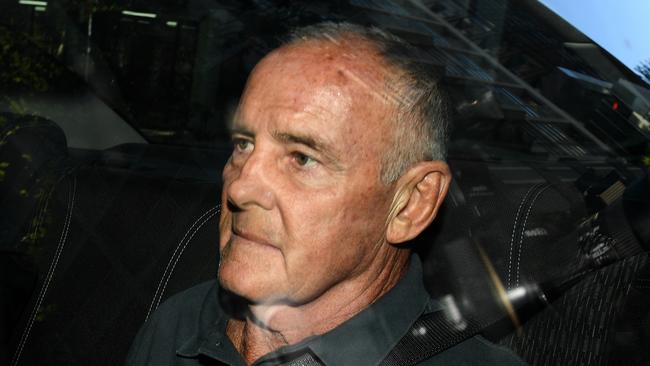

Chris Dawson’s lawyer has admitted it was not ‘admirable’ for the former Newtown Jets star to move his teenage lover into his marital bed shortly after his wife disappeared, but claims it does not prove him guilty of her murder.

Chris Dawson may not have killed his wife even though he moved his teenage babysitter into their marital bed and told her she could wear Lyn’s clothes days after she disappeared, a court has heard.

Opening the former rugby league star’s appeal against his murder conviction on Monday, senior public defender Belinda Rigg SC argued Dawson was deprived the right to a fair trial because of the four-decade delay between the crime and his conviction, and claimed there was not “sufficient evidence” to put him behind bars.

She also said it was possible Lyn abandoned her family because she trusted her “highly capable” husband to run the household, and “would easily have contemplated it well within Dawson’s capacities to look after, admirably, their two children”.

Dawson appeared via video link in the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal on Monday, wearing prison greens and staring sternly at the courtroom. He spoke only a couple of times, verifying that he could see and hear the goings-on of the courtroom.

NSW Supreme Court judge Ian Harrison in October 2022 found Dawson guilty of the murder of his wife and sentenced him to 24 years in prison, following The Australian’s investigative podcast series, The Teacher’s Pet, hosted by journalist Hedley Thomas.

Ms Rigg on Monday told the court Dawson was a devoted father who loved his children, and Lyn left her family due to intense marital problems and issues with her mental health.

She said Dawson’s paternal capabilities enabled Lyn’s “preparedness” to leave her children in his care and disappear on January 8, 1982.

“There was a considerable body of evidence that the applicant was well known to (Lyn) to be highly capable of looking after the children,” Ms Rigg said. “(Lyn) would sit and chat with the other women at … picnics, and it would always be the applicant … changing nappies, taking care of the children’s needs.”

Ms Rigg said Lyn was “not coping” at the time of her disappearance, because Dawson was “not engaging intimately with her” and was “being angry and non-communicative with her”.

Lyn had also recently found her husband in bed with their teenage babysitter, JC, who would later become Dawson’s second wife, Ms Rigg said.

“She had found (JC) topless and naked in her family pool and her loss of self-esteem … was discussed with friends and colleagues,” Ms Rigg said.

NSW Court of Appeal judge Anthony Payne asked if Ms Rigg was arguing it was consistent with innocence that Dawson “moved JC into the marital bed” after Lyn’s disappearance.

Ms Rigg said: “It’s not admirable, it’s not wise. The nature of his interest in JC is, in our submission, related to the very reason why his wife left to take some time to herself.

“They’re not strangely coincidental occurrences, these occurrences are, in our submission, intertwined with one another.”

Ms Rigg said Dawson would deal with the consequences of his decision to move JC into the house if Lyn ever returned.

Judge Christine Adamson asked Ms Rigg about Dawson’s motive to murder Lyn, given his desire to keep the children and the house, as well as his obsession with JC. Ms Rigg told the court JC never indicated the reason she wanted to end the relationship was because Dawson was married.

Justice Adamson said: “Nonetheless, the applicant, from his point of view, wanted to keep the children, wanted to keep the house and wanted to keep JC, and one way of doing that would be to murder his wife.”

Ms Rigg said Dawson didn’t necessarily murder his wife despite those factors. She told the court Dawson suffered a “significant forensic disadvantage” due to the 40 years that passed between the murder and his criminal trial, arguing his defence team was unable to call evidence from key witnesses who had died.

One of those witnesses, Ms Rigg said, was Sue Butlin, a family friend who said she saw Lyn at a roadside fruit barn after her disappearance.

Ms Butlin’s ex-husband, Ray Butlin, was a friend of Chris Dawson from rugby league circles.

While Ms Butlin died before the murder trial, her husband gave evidence about what she had told him, saying: “The substance was that she saw a person that she believed was Lyn Dawson.”

Mr Butlin said his ex-wife “called her name. She walked towards her and the woman proceeded without turning around and got into a car and drove off”.

In his judgment, Mr Harrison said this was a “fleeting” encounter and dismissed it, along with all the other alleged sightings of Lyn after January 9, 1982.

But Ms Rigg said Ms Butlin’s account of her sighting was “quite extraordinary” as she knew Lyn well.

“That’s a very clear example of a deceased person whose evidence was crucial,” Ms Rigg said.

The hearing continues on Tuesday.