China economic troubles fail to interrupt Australia’s trade boom

The policy settings made at a meeting of Xi Jinping’s top advisers will likely pour hundreds of billions dollars into Australia this year | WATCH

China’s once mighty property sector is in a woeful state.

Chinese consumer sentiment remains in the doldrums.

The local sharemarket has been the worst performing in the world.

“It’s grim,” says the head of an international business chamber in Beijing.

President Xi Jinping’s propaganda machine keeps repeating the slogan “The ‘next China’ is China” but foreign investment flows, now at their lowest in 30 years, show few are convinced.

One Australian corporate adviser says almost all of his firm’s China-related work in 2023 involved quietly offloading assets.

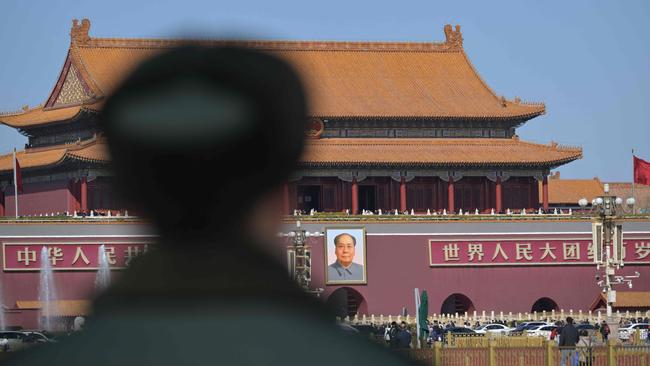

On Tuesday, Premier Li Qiang is going to try to turn all of that around as he takes the podium at the Great Hall of the People and delivers his first government work report – the closest thing China has to Australia’s budget night.

It is the main event at China’s National People’s Congress, the flagship annual political event where policies are announced and personnel are appointed, and a rare occasion when all eyes are not on Mr Li’s boss, Mr Xi.

Analysts expect Mr Li will announce a growth target for China of about 5 per cent for 2024. While that would be slow by the standards of the country’s boom era, it would likely make China the source of one-third of global growth this year.

And it would pour billions of dollars Australia’s way because of our extraordinary complementarity with China’s resource hungry economy.

In recent weeks, Mr Li has said Beijing would set an “active fiscal policy” and “use pragmatic and powerful action to boost the confidence of the whole of society”.

Experts caution against dreams of a “bazooka-style” stimulus package.

Most don’t expect any major shifts in the statist economic vision that has characterised the Xi era.

”Fundamentally, Beijing is expected … to announce tactical measures aimed at boosting short-term confidence in China’s economy but without changing Xi’s underlying strategy of investment-heavy state-guided development,” say the Asia Society’s Neil Thomas and Jing Qian.

More of the same should suit Canberra just fine. Beijing’s seemingly insatiable desire for iron ore and more recent hunger for lithium has made Australia just about the only rich country whose exports to China are booming.

Last year, Australia’s trade with China hit a record. Our exports to China in 2023 were worth $203.2bn – the most ever — while imports from China were $104.7bn. Australia’s near $100bn trade surplus with China is unheard of among advanced economies. Trade Minister Don Farrell reckons things could get better. “Just because we’re doing $300bn worth of two-way trade at the moment doesn’t mean that figure can’t be $400bn,” Senator Farrell said last week.

That was perhaps the most optimistic China trade projection by a Western political figure since Mr Xi entered his second decade in power.

Surviving China’s crisis

There is much attention on the details of whatever stimulus package will emerge this week in Beijing but for Canberra the most important data point may have already been released.

With little fanfare, the China Iron and Steel Industry Association announced a few weeks ago its mostly state-directed members would produce just over one billion tonnes of steel in 2024. That would be the sixth consecutive year China has produced more than one billion tonnes of steel, more than half of the world’s total.

For another year, it will require mountains of iron ore from Australia – by far China’s biggest supplier. The resilience of Australia’s iron ore trade during China’s years-long property slump is remarkable. Last year, those exports were worth $115.4bn, almost 60 per cent of Australia’s total to China. “Rarely has the performance of a major commodity price confounded so many,” said BHP’s chief economist Huw McKay.

The iron ore price did not fall below $100 a tonne for all of 2023.

Understandably, the millions of unfinished apartments China’s fallen property giants have abandoned around the country have received a lot of attention from the international media.

Less noticed has been the sustained output by China’s behemoth steel industry or the profound shift in its end uses.

China’s real estate sector used to consume about 35 per cent of China’s steel; now it’s less than 25 per cent – and much of that is in government-subsidised housing.

What remains of commercial “available-for-sale” apartment construction is mostly being done by state-owned enterprises.

They have been ordered to take over and finish the projects abandoned by China’s fallen private property giants.

The non-property sector now uses the remaining 75 per cent of China’s steel. Much of it is in various nationwide projects that Mr Li will list in his speech on Tuesday: village renewals, rural sewage networks, irrigation programs, interminable power lines, enormous wind farms and still more railway tracks in what was already by the far the world’s biggest high-speed rail network.

There’s also the booming heavy machinery industry, which now consumes almost a third of Chinese steel demand; China’s burgeoning car industry, now the world’s biggest; China’s growing consumer goods industry; and ship construction.

A danger for Australia’s iron ore giants is that “draconian top-down cuts” could be ordered by Beijing if the industry is judged to be too hot. For now though, Mr Xi’s statist economy seems to have no limit to uses for another one billion tonnes of steel.

Grumbles among elite

After a bruising few years, many in China are downcast about the economy’s future.

The experience of Mr Liu, 35, is typical of many in China’s urban middle class. He invested 70,000 RMB (almost $15,000) in shares in a listed construction company, thinking that an area “fundamental to China’s economy” would do well. His plan to grow a fund for his son’s future education has been a disaster. Having thought he had bought at the bottom, the shares have fallen by half again. “It turns out there is a lower point than the ‘low point’,” Mr Liu said.

Experiences such as his are commonplace and partly explain why Chinese tourist numbers to Australia remain lacklustre more than a year after the dismantling of Beijing’s Covid fortress.

For the most part, Australia’s exports to China have been largely protected from gloomy Chinese consumer confidence. Our four biggest – iron ore, lithium, LNG and coal – make up more than 80 per cent of our exports to China.

Their customers are almost all Chinese state-owned companies or private firms receiving huge support from the government.

All are benefiting from Mr Xi’s statist planning, which will be centre stage this week as Beijing sets annual targets for job creation, grain production, military spending and thousands of other measures. This approach is subject to much grumbling in China, at least among its educated elite.

Yao Yang, an economist at China’s Peking University, warns that government officials have become “overly cautious” as they navigate an increasingly risky political environment.

In a much discussed recent essay, he says this was benefiting the state-owned sector at the expense of private businesses.

“For example, to avoid being suspected of accepting bribes, officials have preferred to award government procurement [contracts] to state-owned enterprises with no expertise, allowing them then to subcontract to private firms rather than award [these] contracts directly to private firms,” he argues. “As a result, ‘lying flat’ has become the norm not only for many officials, but also with regards to China’s economy.”

It’s a Xi-era status quo that continues to enrich Australia immensely. And no one should expect it to be overhauled this week.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout