Calls for dementia patient access to voluntary assisted dying scheme

Former chief scientist Ian Chubb has called for dementia sufferers to be allowed access to voluntary assisted dying through a legal framework permitting how they want to die on their own terms.

Former chief scientist Ian Chubb has called for dementia sufferers to be allowed access to voluntary assisted dying through a legal framework permitting seriously ill Australians to leave advanced directives outlining when they wish to end their life.

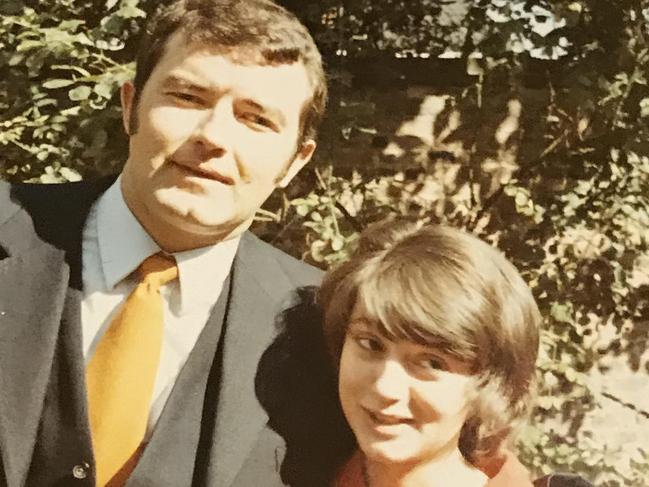

Professor Chubb has spoken out following the death of his wife, Claudette, from dementia at 75, saying she “would have hated knowing what was in store for her when she was capable of thinking about it”.

As the ACT government considers what will be the most liberal euthanasia framework in the country if enshrined into law, Professor Chubb has called for the scheme to include dementia, arguing that a legal mechanism could be designed setting out when a patient wanted to die.

The Labor-Greens government has committed to investigating how it can include people with dementia to euthanasia once the laws – which are being examined by a parliamentary committee – have been passed by the ACT parliament.

Professor Chubb, the chief scientist from 2011 to 2016, penned an emotional submission to the inquiry reflecting on how his wife spent her final weeks in pain, abandoned by her faculties and unable to recognise her own family, without any other choice.

He said he knew she would have chosen assisted dying if it was available, and he would gladly sign an advanced directive to end his life on his own terms if he was suffering from the same illness.

“I’d make the decision now, when I’m cognitively capable and I know what I want,” he told The Australian.

“I’m allowed to have a life plan, so that’s things like you can’t force food, you can’t resuscitate, but what you can’t do is say what you do want done.”

Professor Chubb said cognitively capable people should be able to leave directions for how they wanted to die when the disease had progressed to the point of their choosing, such as when they could no longer recognise where they were or those around them.

“My wife didn’t recognise me for at least a year, she was totally incontinent, she lost all speech,” he said. “She was a linguist, she spoke three languages fluently and two reasonably. She had in the last year or so, three or four words – really only two words but in two languages.

“She was a dignified woman, she would have hated knowing what was in store for her when she was capable of thinking about it.”

Religious leaders including Catholic Archdiocese of Canberra and Goulburn chancellor Patrick McArdle have been staunchly against access for dementia patients, arguing that it was morally fraught to end someone’s life when they no longer had capacity.

“In the typical Australian model of voluntary assisted dying the assumption is you have capacity at the time you make the request,” Dr McArdle said.

“I just can’t see how you can come up with an adequate set of safeguards that envisage this set of circumstances.”

Medical oncologist Cameron McLaren, who is the inaugural president of Voluntary Assisted Dying Australia and New Zealand, said he felt “conflicted personally on the issue”.

“Essentially, it’s me making a decision for someone in the future who is essentially going to be a different person,” he said.

“That’s on a personal level, so I wouldn’t extrapolate a belief on someone else but I believe everyone should have the right to self determination … I don’t see it as anyone else’s duty or responsibility to remove that from them.”

Under the ACT’s draft legislation a terminally ill patient is not excluded from accessing VAD because they have dementia, however it is not grounds on its own to access assisted suicide.

The bill states that a person still has decision-making capacity even if they “make an unwise decision”, “have impaired decision-making capacity under another Act” or “moves between having and not having decision-making”.

Doctors for Assisted Dying Choice said the bill’s lack of time frames for a predicted death would allow access to patients with dementia “who desperately wish to avoid the suffering and indignity of late dementia … before progressive loss of mental capacity renders them ineligible to do so”.

The ACT government said in its submission it had heard concerns from health workers that administering a substance to end someone’s life to an individual who “lacks capacity is highly subjective, ethically challenging, and without precedent in current medical practice in Australia”.

An ACT government spokesman confirmed it would review accessibility for people with dementia after three years.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout