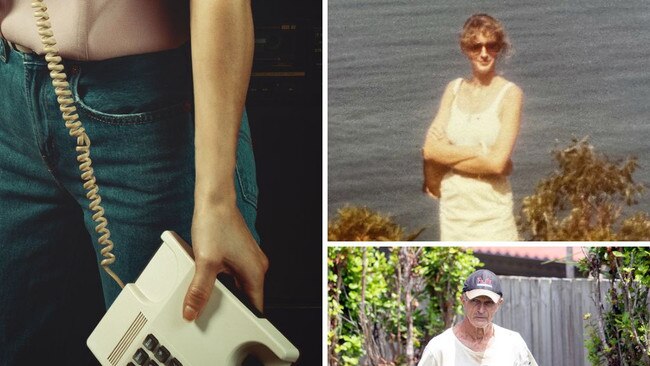

Bronwyn Winfield mystery: Local phone calls the smoking gun

Police failed to properly investigate purported phone calls by Bronwyn Winfield from her home the night she vanished from Lennox Head on the NSW north coast.

Police failed to properly investigate purported phone calls by Bronwyn Winfield from her home the night she vanished from Lennox Head on the NSW north coast.

An exhaustive review of police records by The Australian’s Bronwyn podcast found no conclusive evidence the mother-of-two made the calls before she disappeared 31 years ago.

Bronwyn’s estranged husband and the main police suspect for years, Jon Winfield, insisted she went into a bedroom and made a couple of telephone calls from the landline before a car arrived and picked her up.

Mr Winfield said he only heard and didn’t see the vehicle, with his version of events suggesting Bronwyn must have telephoned someone who then drove to collect her.

No one else saw the vehicle, and Bronwyn was never seen or heard from again.

Discovering who, if anyone, Bronwyn phoned could be the smoking gun that finds her killer by showing who she communicated with just before she disappeared. Or if no calls were made, it would establish Mr Winfield has been lying since the start, creating a hole in a central part of his story.

Records of long-distance calls were obtained by police in 1993 when Bronwyn went missing. But in all of the available documents from this original investigation, there is no evidence detectives obtained data from Telecom for local calls. That’s despite experts including former Telecom worker Linda Horsefield now saying this crucial information was available in 1993 when Bronwyn went missing.

“You’ve always got to show what people are being charged for,” Ms Horsefield told the podcast. “There was so many issues that people had to be reimbursed. We had to be able to see how much they were entitled to.”

She was “100 per cent” confident that data was available at the time showing local phone numbers dialled and the time that calls were made and ended.

“I had access to pretty much all the systems. Especially when there was billing disputes, we had to go through the whole bill. If a person was complaining about drop outs and wanted to get reimbursed, we would pull the local call data. We could actually see all the calls that people used to make.”

Telecom became known as Telstra domestically in 1995, and it’s unknown if the data would still be available today.

“(Police) would have had to ask for itemised call records. And that would show up every call that was made. Definitely local calls were itemised, but it wouldn’t come up on bills. It’s just a matter of how far back they can go,” Ms Horsefield said.

Retired detective Damian Loone, who helped solve the 1983 murder of another missing mother, Lyn Dawson, also recalls that local call data from landline telephones could be obtained in 1993.

The only two phone calls that are known to have been confirmed from the home that evening were long distance to Sydney.

They were to the homes of Mr Winfield’s daughter Jodie, at 6.53pm, and his brother and sister-in-law, Peter and Louise Winfield.

Mr Winfield says he made those two calls, but doubts have been raised about whether he could have been at the house in time to make them. He had just flown in from Sydney that day, with flight records indicating he was likely on a plane that was scheduled to land at 7.25pm.

One theory is that Bronwyn made the two long-distance calls to Mr Winfield’s daughter and brother because she was panicking about her estranged husband returning to the Sandstone Crescent home. She had only moved back into the property with daughters Chrystal, 10, and Lauren, five, two days earlier, while Mr Winfield was away working in Sydney.

Detectives reinvestigating Bronwyn’s disappearance five years later, in 1998, interviewed Mr Winfield at Ballina police station.

Mr Winfield told the detectives that the original lead police investigator, Detective Sergeant Graeme Diskin, informed him that the local calls had been traced.

“Graeme told me that. Where the phone calls were going,” he said.

“Because I was surprised when he told me because I didn’t know you could trace local phone calls. And I had no idea you could do it. And then he told me you could. And he did it, you know?”

At that point in the recorded interview, the audiotapes had to be changed.

When the conversation resumed, Mr Winfield was not asked a simple open question: “Jon, what do you say Detective Diskin discovered when he apparently traced those calls.”

Mr Winfield, 69, continues to strenuously deny any involvement in Bronwyn’s disappearance.