Missing mum Bronwyn Winfield’s family: History is not repeating

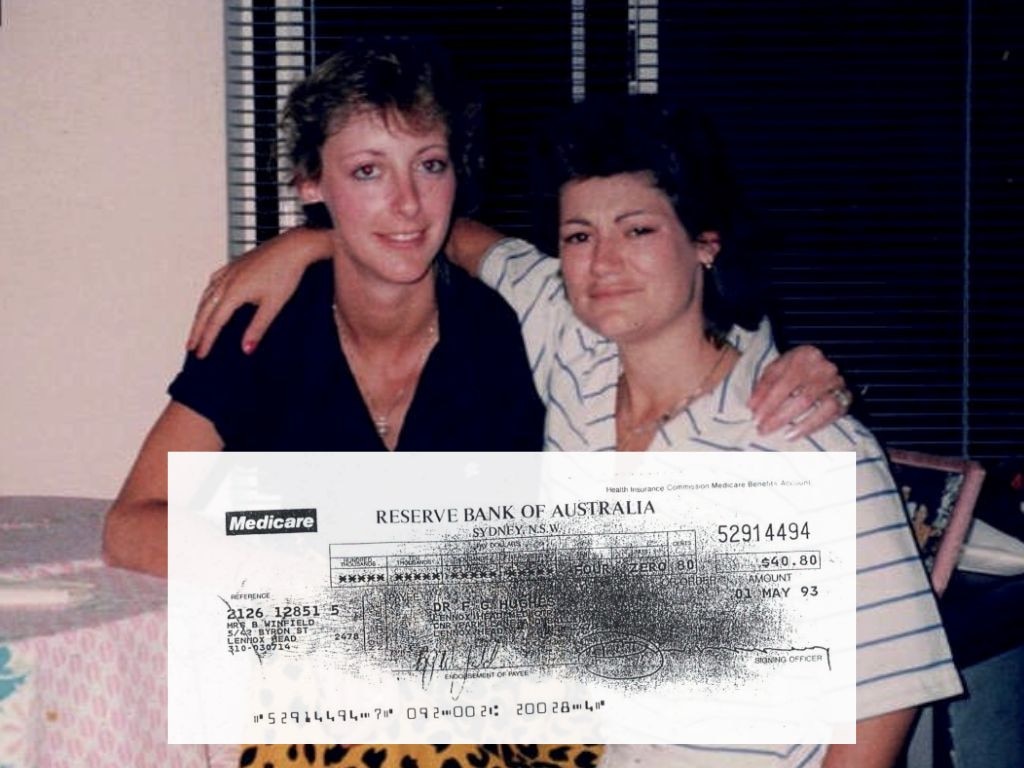

Bronwyn Winfield’s siblings reject the labelling of their mother as a sex worker, accusing Jon Winfield of smearing her to deflect blame | EPISODE 18 LIVE NOW

For more than three decades a question has hung like an accusation over missing NSW woman Bronwyn Winfield: Did she, like her mother, walk away from her life and children?

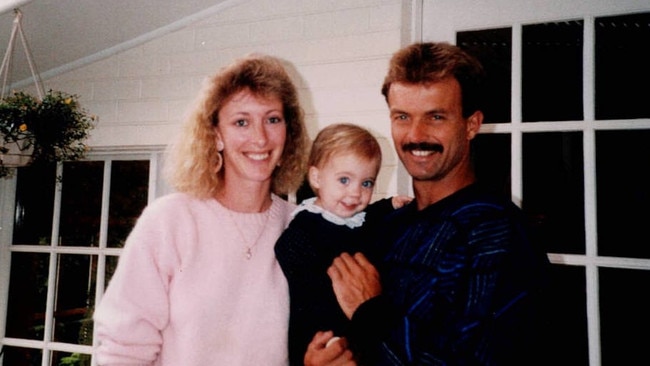

The idea that history was repeating has been promoted and encouraged by Bronwyn’s estranged husband, Jon Winfield, the only known suspect in her presumed 1993 murder.

Five years after Bronwyn went missing from seaside Lennox Head, leaving behind two young daughters she was devoted to, Mr Winfield told police he no longer even thought about what happened to her.

“I just say that one day I hope she’ll pop up because her mother did the same thing,” he said.

Elaborating in that 1998 police interview, Mr Winfield said Bronwyn’s mother, Barbara Read, went to England and “disappeared for 12 years” when Bronwyn and her brother, Andy, were very young. If Barbara could abandon her two children, perhaps Bronwyn could as well.

“I know for a fact that she (Barbara) worked as a prostitute and she will tell you that too, she readily admits it, and that’s where this other child comes from,” he added, referring to the birth of Bronwyn’s half-sister, Kim Marshall.

But for the first time it can be revealed Bronwyn’s mother gave a raw and open statement to police spelling out a life that was very different to her missing daughter’s and the picture portrayed by Mr Winfield.

Opening up on her own mental illness struggles and depression, she said the truth about her life story was even more extraordinary – that desperately missing her children, she took to the streets to conceive a child.

Ms Marshall and Andy Read have also used a new episode of the Bronwyn podcast to reject the labelling of their mother as a sex worker, accusing Mr Winfield of smearing Barbara to deflect blame.

Barbara Read was 59 when she spoke to a detective in the months after Mr Winfield’s 1998 police interview.

Her remarkable and highly personal police statement is detailed in the Bronwyn podcast, with the support of her surviving daughter, Ms Marshall.

Barbara said that after Bronwyn was born she suffered severe postnatal depression.

She saw a psychiatrist, followed the medical advice, recovered and had a son, Andy, before being rocked by the death of her father.

After a holiday away, she returned to find the locks had been changed.

Her husband, Phillip, told her in no uncertain terms “he wasn’t letting me into the home and that our marriage was over”.

Bronwyn was three and Andy was five months old, and legal proceedings began over custody.

“They told me that I would not stand a chance in a court because of my illness and they were claiming that I was an unfit mother,” she said.

With her mental health rapidly deteriorating following the separation, she “decided not to contest for custody and to let Phillip have the children”.

Barbara’s mother, attempting to help her out of her deep depression, suggested they go overseas.

Before they could leave, Barbara overdosed on sedatives and almost died, ending up in intensive care at Sydney’s Mona Vale Hospital.

Released from hospital, Barbara went to the UK with her mother, travelled through Europe on money from the sale of the family home, then worked as a nanny in London.

When she returned to Australia she saw numerous doctors and was eventually diagnosed with schizophrenia.

“I then went to Sydney and I decided that I wanted to have another child because I was unable to see my other two children,” she told police.

“I went to Kings Cross and walked the street, and over a period of three nights and four days during the middle of my menstrual cycle, I had intercourse with eight different men who were all of European blood.

“I wanted a child with European blood. So I picked three Italians, one Yugoslavian, one Hungarian, one Englishman, an Australian, and one American from the streets around Kings Cross. Shortly afterwards, I discovered I was pregnant. But I do not know which one was the father.”

Only the detective who took the statement can know for sure why it was relevant to take down these details.

One possible reason was that it showed there was a lot more to Barbara’s story than a woman walking out on her daughter and baby son.

She missed her children so badly that she was prepared to do almost anything to have another.

Ms Marshall has told the investigative podcast series that her mother, “being the incredible person that she was”, told her from the youngest age about where she came from and why.

“My mum didn’t prostitute herself. I knew the reason that I was conceived. And I think I wore that with a badge of honour. I was what kept her alive,” she said.

Bronwyn’s cousin, Madi Walsh, said Barbara and Bronwyn, and what they went through, were very different.

“Barbara disappeared from her kids’ lives when they were very young and it was due to Barbara’s mental health issues,” Ms Walsh said.

“There’s this pattern that kind of emerges here where we see two young mums being pushed out of their kids’ lives. Jon created a bit of this pattern because he created this idea that Bronwyn was going through what her mother went through, these mental health challenges, and that’s why she left.

“We know with multiple witness recounts and witness statements later on that Bronwyn wasn’t going through what her mother went through. Jon created that and led with that. And the police listened to that and believed that.”

Barbara said that in 1975 her ex-husband, Phillip, phoned to say her children, Bronwyn and Andy, wanted to see her.

Bronwyn, who turned 13 that year, and Andy had been brought up to believe their stepmother was their birth mother, and had to adjust to a new reality.

Barbara was “thrilled” to reunite with her children, saying she had not seen them for 11 years.

They had a “wonderful reunion” and had kept in constant contact ever since, she told police.

Barbara died in 2006, four years after coroner Carl Milovanovich terminated an inquest and recommended Mr Winfield be charged with Bronwyn’s murder.

Prosecutors declined to charge him, citing insufficient evidence. He is now 69 and still emphatically denies any involvement.

In her last days alive, suffering pancreatic cancer, Barbara tried unsuccessfully to see her grandchildren, Bronwyn’s daughters Chrystal and Lauren.

Phoning Mr Winfield, she was “hoping to speak to Lauren and ask if it would be possible for Lauren to come down to see her”, Ms Marshall said.

“Unfortunately, Barbie’s requests were denied. I know she shed tears that afternoon, as I stayed behind that day and kept an eye over my beautiful mum until her carers had got her ready for sleep,” Ms Marshall said.

“Her weeping was silent and as always she did not complain to her carers nor let her sadness overtake her. My mother was the most graceful woman this day. Earlier we had all cried from our disappointments, and Barbie consoled us and guided us to move onwards.

“She expressed that too much time had passed and it was probably best to just let things be.”

Andy Read said Mr Winfield could not answer key questions about the night Bronwyn went missing.

“But all of a sudden his memory is just razor sharp on all sorts of other major issues, including coming up with this opinion of Mum,” he said.

Mr Winfield said in his police interview that not long before Bronwyn went missing, she told him she had had a nervous breakdown, similar to her mother’s experience.

In his only response to repeated approaches from The Australian, Mr Winfield also said: “There is a generational history of mental illness, both male and female, in the Read family.”

Police involved in the 1998 reinvestigation could find no evidence Bronwyn was treated for a nervous breakdown or mental illness.

A copy of Bronwyn’s monthly telephone bill shows she called her mother at her home in Tasmania on Mother’s Day 1993, a week before she disappeared. It appears that after everything they had been through, they were on good terms.