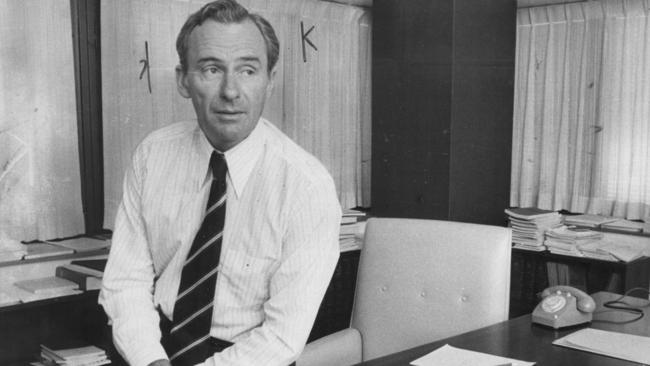

Bill Hayden: A legacy of achievement for a selfless leader

Former governor-general and federal Labor leader Bill Hayden, who was famouly deposed by Bob Hawke just before the victorious 1983 election, has died, aged 90.

Born January 23, 1933, Spring Hill, Queensland

Died October 21, 2023

Bill Hayden won many of the glittering prizes in Australian politics from treasurer and foreign minister to Labor leader and governor-general. He dedicated his life to public service and left a legacy of achievement. But not becoming prime minister — instead resigning the Labor leadership to make way for Bob Hawke — hurt like hell.

“I was in personal turmoil about stepping down as leader,” Hayden said in 2017 in an interview with The Australian. “It hurt a lot. I worked hard. I was away from home a lot. It caused a lot of grief with my two daughters and my wife, who had given a lot to support me … I felt like a total failure.”

After agreeing to resign during a break in a shadow ministry meeting in Brisbane, paving the way for Hawke to become Labor leader, Hayden locked himself in a bathroom and wept. That same day, Malcolm Fraser called a snap election and weeks later Hawke was prime minister.

Hayden had served as minister for social security (1972-75) and treasurer (1975) in the Whitlam government, and it was in those three tumultuous years in Australian politics that he was most proud of. He won the fight to establish Medibank, the first national health scheme, and funded new benefits for single mothers.

“(Medibank) gave ordinary people a chance to have the best medical service available, and hospital care, and they did not have to worry about becoming indebted,” he told me in an interview in 2022. “It was their health that mattered and determined the outcome.”

He often recalled being stopped in a supermarket by a woman who thanked him for introducing the supporting mother’s benefit for unmarried women during the Whitlam government. “I’m studying at university because of you,” she told him.

The Whitlam years prompted mixed memories. Hayden never thought the Queen had anything to do with Whitlam’s dismissal by Sir John Kerr in November 1975 and regarded those who propagated such nonsense as having a “shallow grasp” about the vice-regal relationship.

Feelings about Hawke ran hot and cold. Hayden stressed for the record that Hawke was a fine prime minister. They got on well in government. Hayden served as foreign minister from 1983 to 1988. There was mutual respect between both men if not affection.

“Bob always regarded himself as a great politician and he was,” Hayden told me in 2019. “That was why I called him the Don Bradman of Australian politics when he died because, although not everything he did was perfect, he had a very high average when it came to political successes.”

‘I put my leadership on the line without consulting anyone. I just did it. We had to; the party was going nowhere.’

Hawke made life difficult for Hayden. Asked in 2017 what he thought when Hawke entered parliament in 1980, he replied: “Oh, here comes bloody trouble. One of the most popular blokes in Australia. I was under no illusion there would be a lot of pressure.”

He became the bridge between the Whitlam and Hawke-Keating governments. After the 1977 election, Hayden defeated Lionel Bowen by 36 votes to 28, and became Labor leader. His core goal was to rebuild Labor’s economic credibility. “We cannot achieve social reform unless we competently manage the economy,” Hayden told the party’s 1979 national conference.

Reforming Labor in the post-Whitlam years was also a Hayden priority. He democratised and enlarged the party, developed new policies such as Medicare, recruited new candidates and refreshed the front bench. “I put my leadership on the line without consulting anyone. I just did it,” he recalled in 2014. “We had to; the party was going nowhere.”

In 1980, Hayden almost defeated Fraser when Labor won 13 seats and secured 49.6 per cent of the two-party vote. Still, Hawke was unrelenting. One night Hawke went to Hayden’s office, sat down and took a poll out of his jacket which showed Labor would be better placed to win an election under him. Hayden promptly told him to get stuffed.

Hayden’s judgments about Hawke could be cutting. Hawke appointed Hayden governor-general (1989-96). It is an irony of history that Hayden received Hawke’s resignation as prime minister after he was defeated by Paul Keating in a leadership ballot in 1991. What was running through his mind? “Those who live by the polls can die by the polls,” Hayden said.

On the phone, he would quote Shakespeare’s Othello and Coriolanus. He would sing love songs to his wife, Dallas, in earshot. He talked about movies. He was immensely proud of his children. He lamented not being able to celebrate his 60th wedding anniversary at home with friends and family due to the covid pandemic.

He remained a close observer of politics. “I’ve never seen a treasurer spend so much money,” Hayden said of Josh Frydenberg early in the pandemic. “It must worry him because it worries me as a former treasurer. The government has done a lot but it is costing a lot.” He predicted prolonged high inflation.

The final decade of his life was a struggle. He had been in and out of hospital for strokes, pneumonia, heat exhaustion and broken bones. at a hospital in Brisbane just weeks after Whitlam’s death in 2014, he was emotional. He had a difficult upbringing and the setbacks in his career had a searing impact.

Hayden was born during the Depression, on January 23, 1933, the eldest of four children to Violet Quinn and George Hayden. He was raised in poverty in South Brisbane. His drunken father beat him with a rubber hose. He understood what Ben Chifley meant when he spoke of the lottery of life and “the shafts of fate” that can shape a person.

Before being elected as the federal member for Oxley in Queensland, Hayden worked as a public servant and police constable (1953-61). It also shaped him. He witnessed horrific things: women violently assaulted by their male partners, alcohol and drug abuse, children living in squalor. And police that engaged in, or turned a blind eye to, sleaze and corruption.

His marriage to Dallas Broadfoot in 1960, brought him happiness, companionship, support and reassurance. They raised four children, Michaela, Kirk, Georgina and Ingrid. But tragedy struck when the eldest, Michaela, was killed by a car when she was five years old. The trauma never left him.

Prone to depression, which often manifested as self-doubt, he lacked qualities necessary for successful leadership: confidence, ambition and, sometimes, ruthlessness. Hayden did not have the killer instinct. He was never supremely confident or self-assured as Labor leader, and was often suspicious and not fully trusting of his colleagues. He was painfully insecure.

Many years later, I asked about the diaries he had kept while an MP. “I tore out the guts of about half a dozen hard-cover, bound, quarto-size books with ruled pages about a year ago and put them through the shredder in my office,” he told me in 2015. “I suspected journalists would openly fight over superlatives to describe how badly kept they were and the poor grammar.”

Looking back, Hayden admired Whitlam’s intellect and courage but he was not blind to his faults. “Gough had good policies but the problem was they were implemented too rapidly,” he said in 2022. “I thought we can’t keep going on like this and that Gough should have exercised more discipline over his ministers.”

During the Whitlam government, Hayden was eager to be appointed Treasurer. He wrote Whitlam memos about economic decisions as he fretted over the government’s economic credibility waning, and the performance of Frank Crean and then Jim Cairns as Treasurer. “They were both disasters,” he reflected in 2023. “I felt we needed a steady hand on economic management because things were spiralling out of control. We were spending too much money.”

He undertook a Bachelor of Economics at the University of Queensland as an external student and graduated in 1969. He remembered sitting in the Parliamentary Library late at night studying. He remembered other MPs perusing the books, magazines and research files, including a “bald-headed and bow-legged” Billy McMahon “always getting up to mischief.”

In 1975, he finally got his chance. The Hayden budget helped to restore the government’s economic standing. But it became the subject of a battle of brinkmanship as supply was delayed in the Senate and Kerr dismissed the government. Hayden had briefed Kerr on the government’s plan to fund salaries through private banks. He told Whitlam his “copper’s instinct” told him that Kerr was not onside. Whitlam ignored the warning.

At the 1975 election, Hayden nearly lost his seat of Oxley. He held it by 112 votes. Whitlam phoned to offer him the Labor leadership. Hayden was exasperated. “Jesus f--king Christ, Gough, I don’t even know if I’m going to be in the bloody parliament,” he responded. He declined and refused to immediately serve on the front bench. In 1977, Hayden challenged Whitlam for the leadership. He almost won – the vote was 32 to 30 – but he later regretted it.

Keating encouraged Hayden to run for the leadership in 1977. They liked and admired one another but Keating knew Hawke guaranteed a Labor victory in 1983 whereas with Hayden it was likely but not certain. Keating voted for Hawke when he challenged Hayden in 1982, and lost 42-37. Hayden, however, always admired Keating.

“He walked with confidence,” Hayden said of Keating in 2015. “He was going places because he was intelligent, capable, and courageous. He understood power. He knew what he was doing and where he was going.” Keating reminded him of a Spanish matador, with courage and style, and not in the least intimidated when facing a determined bull.

When Hayden granted me access to his sealed papers at the National Library of Australia, I discovered a series of letters he exchanged with Hawke about the leadership in 1983. He drove a hard bargain and extracted from Hawke a series of written guarantees. Nobody knew such letters existed.

‘I could just feel in my heart that I didn’t feel fulfilled.’

There were many sides to Hayden. I also found a series of letters he wrote about police brutality towards homosexual men. In 1988, he wrote to Queensland Premier Mike Ahern saying he was “horrified” about the “vindictive conduct of the police” which was “out of touch with contemporary tolerance and understanding”. He threatened to go public unless Ahern took action. In 1967, Hayden advocated decriminalisation of homosexual acts between consenting adult males in private, following the same legal reforms in the UK.

During the 2022 federal election, Hayden was eager to speak to Anthony Albanese. He had no luck getting through to him via the Labor leader’s office. I contacted Albanese after the election and suggested he give Hayden a call. When they spoke, Hayden had a request for the new prime minister.

“I spoke to Albanese and asked him to consider me for appointment as the Australian High Commissioner in London,” Hayden told me weeks later. “He said when he made a decision, he would let me know.” He phoned months later to register his disappointment when Stephen Smith got the job.

Some of Hayden’s old Labor colleagues joked he was taking out insurance as the end neared. At age 85, he renounced his atheism and was baptised into the Catholic Church. He had attended a Catholic primary school and went to church regularly in his youth but later discovered he had not been baptised.

“I could just feel in my heart that I didn’t feel fulfilled,” he told me in 2018. “There is more to life than just me. I had to make a dedication of myself for the good of others, before God. I felt that strongly.”

Hayden was a participant in politics for almost four decades and also an eyewitness to history. It was fascinating to listen to him recall Robert Menzies, John McEwen, Harold Holt, John Gorton, McMahon and Whitlam. He vividly remembered the young Keating elected in 1969 and the young John Howard in 1974.

He had sat in the House of Representatives in the Old Parliament House during the Vietnam War, remembered sectarianism and the fear and hostility generated during the Cold War. But it was his own contribution that I often asked him to reflect upon. It was simply about serving others and serving well.

“You asked me about what I’m proud about my time in government,” he told me in 2020. “Well, I hope people can say he used his time in office fairly and helpfully for those who had a need for help, and he did it honestly and with integrity. You can’t ask for more than that in public life.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout