China has 1.4 billion people, an army of two million and the capacity to build a nuclear submarine in 15 months, but is it united by anything other than the convenient belief in a state that has delivered a rising standard of living (largely by doing business with the West)?

China needs a narrative that galvanises its masses: righting past wrongs and the decline of the (immoral) West are popular themes.

A curated media and social media are preferred platforms.

There is another imperative for China and that is a demographic window within which to undertake expansionist objectives, to pursue the ideal of reunification (and more besides), to embark upon who knows what military adventurism.

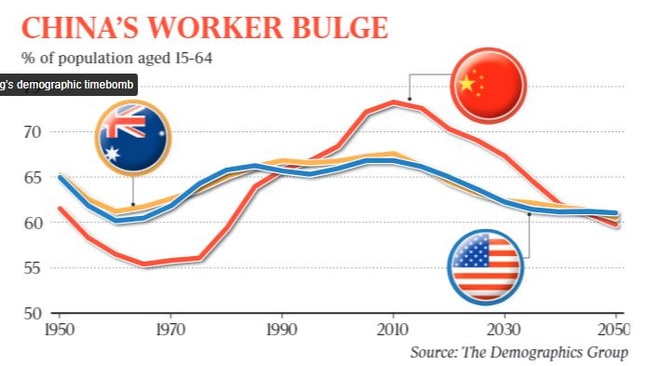

China’s pursuit of the one-child policy from 1975 onwards delivered a demographic boost to its economy: more taxpaying workers and fewer kids requiring education and support services delivers government with excess spending capacity.

This is another way of expressing the dependency ratio: this is the number of non-workers (kids, old people) per person of working age (15-64).

China’s productive 15-64 cohort peaked at 73 per cent of the national population in 2010 (see chart). Indeed, there is a 45-year window between 1995 and 2040 during which China should have excess spending capacity that could be directed to military (or other) objectives.

Of course, an authoritarian regime can impose its will upon its people at any time but outside this “demographic window” such redirection of funding comes at the expense of investment in, say, civil infrastructure, social welfare programs and healthcare. Such actions risk a breakdown in social cohesion and belief in the state.

We are halfway through China’s one-child policy-induced demographic window. And the fact that nothing militarily (other than sharp verbiage) has happened as yet kind of makes sense: the first two decades of this surplus spending is spent building new airports, fast trains, social welfare programs and maybe even a space program.

If there was a best demographic time to pursue a grander vision without imposing undue impact upon a people (that have become used to comfortable way of life), that would be the period 2020-35.

China’s President Xi Jinping is now 68. No point achieving reunification if you’re too old to bask in the glory of a grand vision boldly achieved … best to get the kinetic side of the plan done and dusted by your early 70s.

The demographic message for the West, and for the US and Australia in particular, is that at some point, perhaps just beyond the current administration’s tenure, in say the early- to mid-2030s, China’s focus must shift to meeting the demands of an increasingly aged society.

Then again, maybe China is well aware there is a demographic sweet spot within which it must establish new supply lines (Belt & Road Initiative), secure compliance from resource-rich states (such as Australia), and perhaps even establish global bases (such as in the Pacific) from which its authority might be projected (in much the same way as was done by the French, British and Americans during their times at the top).

Stall, obfuscate, postpone, create a counter narrative, engage in diplomatic double-speak, do whatever is required to keep kicking the can down the road to the mid-2030s when China’s focus will shift to the demographic consequences of 35 years of the one-child policy.

By the 2040s, China’s aged will absorb such a portion of the nation’s productive capacity that other grander visions will surely fall by the wayside. Or at least that’s the theory behind China’s demographic window.

Recent efforts to address China’s low birthrate appear to have failed. The National Bureau of Statistics revealed this week that newborn numbers in China fell for a fifth straight year to the lowest in modern Chinese history, despite Beijing’s increasing emphasis on encouraging births.

There were 10.62 million births in 2021, down from 12.02 million in 2020, barely outnumbering the 10.14 million deaths, suggesting the day may be near when its population starts to shrink. At the end of 2021, China’s population was 1.413 billion, up only 0.034 per cent from the year earlier 1.412 billion at the end of 2020. The birthrate – the number of births per 1000 people – slipped to a fresh low of 7.52 in 2021 compared with 8.52 in 2020.

Since a rise in 2016, when China scrapped the four-decade one-child policy and allowed married couples to have two children, the number of births has slipped every year. The birthrate was already the lowest in the country’s modern history in 2019.

According to the World Bank, China’s economy as measured by gross domestic product was $US15 trillion or 70 per cent of the US economy in 2020. A decade ago, China’s economy was barely 40 per cent of the US.

The IMF already places China at 73 per cent of the US in 2021.

At no point during the Cold War did the economy of the USSR ever seriously challenge the economic supremacy of the US, although some estimates suggest it got to 50 per cent before collapsing in 1989.

Today, the trimmed Russian Federation generates an economic output (in $US) 12 per cent greater than that of Australia (in 2020), but with more than five times the population.

IMF figures for 2021 place the Russian economy at 6 per cent greater than Australia. Russia, like Brazil (and others), has had a particularly bad pandemic.

In economic terms, China is closing the gap on the US to the extent that it may become the largest economic force on the planet in the late 2020s.

China is many years away from being able to match the US in annual spending on the military. And matching US spending in one year doesn’t offset the fact the US has been building military capacity at this level for decades.

The US replaced Britain as the world’s largest economy soon after the American Civil War but didn’t project its force globally until after World War II. Britain assumed the mantle of prevailing world superpower from France in the decade after the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. The switch between prevailing and presumptive global superpowers isn’t always settled by conflict but it can come to that.

No empire lasts forever. Not France. Not Britain. Not the US. That doesn’t mean America’s time at top is up in the 2020s. What is required to sustain an empire is supply lines, alliance and, above all, social cohesion.

Bernard Salt is executive director of The Demographics Group

Beijing’s one-child policy provided an economic boon for China over the past two decades but has created a demographic timebomb that gives the world’s most populous nation little more than a decade to achieve any expansionist ambitions.