Time has softened the sharp edges of grief for Bali bombings survivors

It has taken almost two decades for the unthinkable to become possible, and when it happened no one was more surprised than Tumini.

It has taken almost two decades for the unthinkable to become possible, and when it happened no one was more surprised than Tumini.

The 47-year-old, a young bartender at Paddy’s Bar on the night of the 2002 Bali bombings, was talking with other survivors of the region’s worst terror attacks last October when one of them cracked a joke.

“Someone said ‘I was up a ladder fixing the electricity’ and another said; ‘Lucky for you, otherwise you would have lost your head’,” Tumini recalls.

Everyone laughed, and then it struck her.

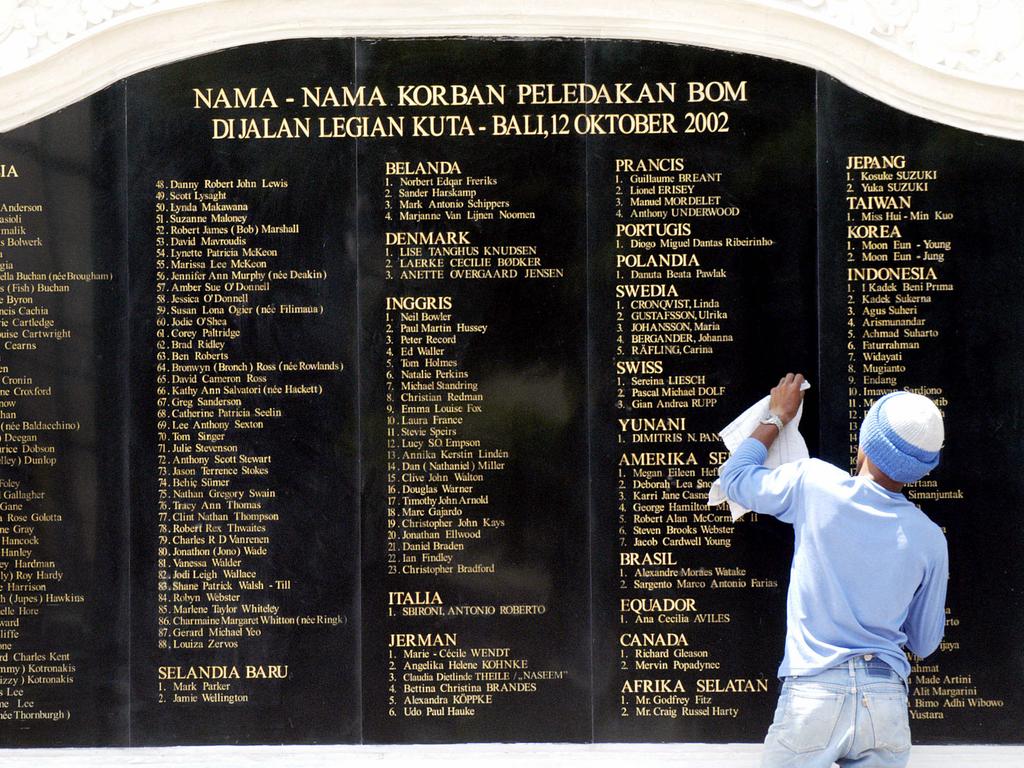

“We are finally able to joke about it, even if we will never be 100 per cent healed,” Tumini told The Australian ahead of the 20th anniversary of the bombings that took 202 lives, including 88 Australians and 38 Indonesians.

For the mother of three – who has undergone numerous surgeries for the injuries she suffered that night, and faces more operations later this month – October 12, 2022, is a day to mourn the dead, but also to acknowledge another 20 years of life.

Stripped naked by the force of the bomb and the fire that enveloped her body, Tumini had staggered into a pool behind Paddy’s Bar to extinguish the flames only to realise on impact that her stomach had been torn open.

Ferried from the bomb site by a foreigner whose name she never learned, she lay for six hours among the dead in the carpark of Sanglah hospital, holding her intestines in her right hand, before her sister and brother-in-law found her.

“At that time I had a daughter and a son, aged six and two, and I really wanted to live. I thought, ‘If I die, who will take care of my children?’,” Tumini told The Australian at a Bali gathering last week with her husband, grandson and a third son, now 14, whose birth was the ultimate life-affirming act in the wake of the terror.

When overwhelmed doctors finally began treating her, she feared again she might die.

“They peeled back my skin without anaesthesia, like I was a chicken. I pleaded with them to stop, it was so painful, but they told me if they didn’t do it immediately it would cause infection. So I had to be strong and think of my young children.”

It has taken years for Tumini to shed the fury that consumed her, and fuelled a constant urge to lash out at others – substitute targets for the “smiling assassin”, Amrozi, who had laughed in the dock when asked if he felt sorry for his victims.

During his trial, she asked the judge for permission to shake the terror ringleader’s hand.

“If he had let me, I planned to punch him in the mouth. Much later I finally managed to punch his brother, Ali Fauzi, when he was let out of prison,” she confessed with satisfaction.

For those who lost loved ones in the bombings, the light can be harder to see as each year marks yet more life events without them.

Limna Rarasati was 12 when she lost her father, Made Sujana, a security guard at the Sari Club who took the force of the one-tonne truck bomb detonated outside the popular venue.

It was a month before Made could be identified with the help of DNA from his unwashed clothes and an old toothbrush, and when he was finally returned to the family it was in eight small pieces.

“My father was almost 180cm tall and all that was left of him was those eight pieces wrapped in an envelope,” the now 32-year-old, mother of two said.

Made Sujana has appeared to his daughter in dreams and – she believes also – in the body of her mother-in-law on her wedding night in 2016.

“In Bali we believe in spirits. I knew my father wanted to ‘borrow’ my uncle’s body to speak to me, but he (uncle) refused. Then later that night, my father possessed my mother-in-law and told me he gave his blessings,” Limna said softly.

“I am so glad it happened.”

Ni Luh Erniati waited four agonising months for news of her husband, Gede Badrawan, the Sari Club’s handsome head waiter, who was standing near the bomb-laden van when it detonated.

So many times she imagined him walking through the door, ending her anguish and the confused grief of their sons – aged nine and 18 months – even as she knew in her heart he was already gone.

Like Tumini, she too felt consumed by a rage that boiled over during Amrozi’s trial when she famously lunged at the grinning terrorist, only to be pulled back by courtroom officials. Her husband’s murder had left her not only tormented by loss, confounded by how to comfort their children, but also a single parent struggling to survive.

“We all know in society a widow carries a certain stigma,” Ni Luh said.

“For a long time I couldn’t accept it and refused to change my relationship status in my government ID. In the end I had to.”

With help from an Australian benefactor, she joined a sewing circle to make ends meet and, though that group has since fallen apart, continues to earn a living through tailoring.

Her eldest child is now a medical biologist, her youngest a university student, thanks to the Indonesian government’s education subsidies for survivors and families of bombing victims.

The photograph of her husband – for years tucked in a cupboard to spare her children – is back on the wall as time has softened the sharp edges of their grief.

Ni Luh’s own search for peace has taken her down a surprising path, into the very heart of the largely defanged Jemaah Islamiaah network by way of the Alliance for a Peaceful Indonesia, a project that seeks to reconcile terrorists with their victims.

She has met several former JI militants including Ali Fauzi, a specialist bombmaker who has since renounced violence and whom she now considers a friend.

Last month, she also met Umar Patek in prison, weeks after the remorseful former militant became eligible for parole 11 years into a 20-year sentence for his role in the Bali attacks.

The 53-year-old wept at her feet and begged for forgiveness.

“I didn’t know what to do to stop him. I just told him, ‘I already forgive you’,” she said.

“I may be different from other victims who are still angry but if I hold on to that anger and hatred I will feel hurt, and I don’t want to be hurt. I have to think of the future because I have two sons who need me. It is important they don’t carry resentment … We have to make peace with ourselves, with others, and with our surroundings.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout