Bali bombings were a failure of intel sharing

But the second front never materialised and, with hindsight, Southeast Asia gave the world a glimpse of an alternative to the so-called global war.

Close co-operation between Australian and Indonesian police to capture the key perpetrators of Bali set the scene at a critical moment in Indonesia’s transition to civilian rule. As the US Department of Defence and the CIA came to capture American counter-terrorism policy, civilians by and large had primacy in the fight against al-Qa’ida and Jemaah Islamiah in Southeast Asia.

But this was not inevitable. Indonesia had only just emerged from decades of military dominance under president Suharto, and after Bali the army jockeyed to take the counter-terrorism lead away from the national police.

Until today the war against terrorism in Southeast Asia largely has been run as a police operation, not a war. At the centre of the action, counter-terrorism scholar-officers in Indonesia and Malaysia were allowed time to develop deep expertise on militant Islamist networks and ideology.

Tito Karnavian, former chief of Densus 88 (the national police counter-terrorism squad) and now Home Affairs Minister in the Joko Widodo government, completed a PhD in Singapore on JI’s process of radicalisation while he interviewed central figures such as Hambali, detained at Guantanamo Bay.

Dato Ayob Khan, Malaysia’s veteran former Special Branch counter-terrorism chief, hunted al-Qa’ida and JI leads from the mid-1990s until the Islamic State era. In 1995 he worked with Philippines police counter-terrorism officer Rodolfo “Boogie” Mendoza to disrupt the Bojinka plot, the precursor to 9/11.

The Bojinka plot was the moment al-Qa’ida’s Khalid Sheikh Mohammed first conceived of using planes as missiles, and had it succeeded more people might have died than on September 11.

In the US, by contrast, as the war on terror gathered force, the CIA sidelined the FBI with its thuggish and pseudoscientific “enhanced interrogation” program. FBI al-Qa’ida experts such as Ali Soufan were forced to withdraw from the field. Key intelligence was lost or contaminated in the cells of CIA black sites around the world. Soufan has long maintained that traditional police interview and intelligence methods were working to unravel al-Qa’ida when the US replaced them with rendition (covert transfers) and torture. The truth of this can be seen in the light of Southeast Asia.

Police abuses and failures did occur in the region, no doubt. But the broad approach in reducing terrorist capability, if not intent, has been an anticlimactic success.

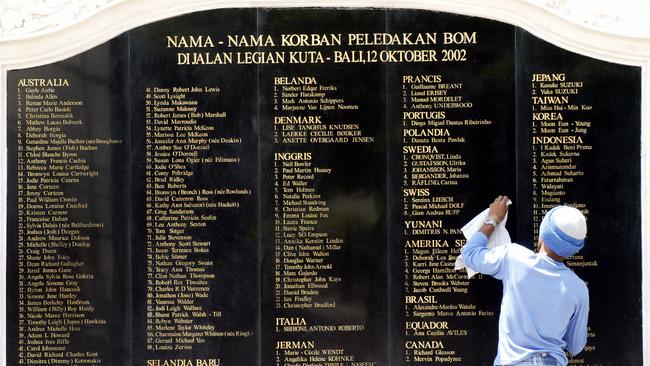

As al-Qa’ida and the Taliban entrench themselves in Afghanistan once more, whether the US ultimately lost the war on terror has become a live question. But in Southeast Asia civilian authorities quietly won the war by disrupting JI networks from within and isolating new variants such as Islamic State. Even in the southern Philippines, where al-Qa’ida and JI were once enmeshed in one of the longest running insurgencies in the world, a peace deal with Manila has the insurgents demobilising and the terrorists scattered. Traditional police work by the FBI also brought us the closest we came to advance warning of the October 12 Bali bombings.

In January 2002, nine months before the attack, Hambali and other key militants fled to Thailand where they found a haven from which to plot strikes against the West. It was in Thailand, a regional tourism hub famous for its Khao San Road backpacker strip, that Hambali directed Bali bombing mastermind Mukhlas and lead bombmaker Azahari Husin to shift attention to soft Western tourist targets. According to Mohammed Mansour Jabarah, a young al-Qa’ida operative who met Hambali in Thailand in January, “His plan was to conduct small bombings in bars, cafes or nightclubs frequented by Westerners in Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines and Indonesia.” Hambali said he had acquired one tonne of explosives in Indonesia.

Jabarah was a liaison between al-Qa’ida and JI, and as such held unique insights into the network. He had been in close contact with Hambali and a dozen JI operatives as part of a failed 2001 operation to bomb Western targets in Singapore, including the US embassy and the Australian high commission. The plot foundered on the difficulty of getting explosives into the city-state. In November, following a tip-off, Singapore arrested several local JI operatives involved in the plot. Hambali advised Jabarah to leave the country before “his picture showed up in the news”.

Jabarah was arrested in Oman, where he was handed over to Canadian authorities, who in turn handed him to the FBI. Lucky to avoid falling into the hands of the CIA, Jabarah then collaborated closely with FBI special agents to identify scores of al-Qa’ida operatives, their contact details and details of his operations in Southeast Asia. By May 2002 his interview transcript ran to about 40 pages.

The question of whether the Jabarah information about “bars, cafes or nightclubs” was picked up by the Australian intelligence community was the closest we came to a post-9/11 debate about intelligence sharing. Conflicting evidence was presented to the 2004 Senate inquiry about whether the material was communicated to Australia’s peak intelligence agency, the Office of National Assessments. The inquiry concluded that due to delays on the American side, the material was made available only after the October 12 Bali bombings, in November.

“If such information had been available to Australian agencies in the middle of 2002,” the inquiry found, “it may well have led to a more explicit warning to Australian travellers about the dangers of congregating in clubs and bars. It may also have led Australia’s intelligence agencies to strengthen their reporting about the vulnerability to attack of tourist spots such as Bali.”

If it’s true that Australia wasn’t keeping up with the Jabarah revelations it exposes weak relations with our Southeast Asian neighbours. The material is known to have been circulating among governments of the region before October. But the greatest intelligence failure on the path to the Bali bombings was in the largely unknown case of a Malaysian man travelling in the opposite direction to Jabarah.

In January 2002, Masran bin Arshad, an unlikely al-Qa’ida member who had become close to Osama bin Laden, was en route from Afghanistan to Thailand. He had been tasked by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed to meet up with Hambali and lead a post-9/11 wave of attacks. But he was arrested in transit in Sri Lanka and handed over to the CIA.

Expert interviewers might have used Arshad to track Hambali and other Bali plotters in Thailand. Instead, he was disappeared into a CIA black site in the Middle East. Incapacitated by torture, he went silent, and after seven fruitless months the agency swapped him in a prisoner exchange with the Malaysian government.

Only back home in Malaysia, recovering from his injuries, did Arshad begin to talk. But by then it was too late. After two months in Thailand, Mukhlas had returned to Indonesia with money from Hambali and a vague plan that sharpened into focus at a meeting with other JI operatives in August 2002. Hambali was eventually arrested, still hiding in Thailand, in August a full year later.

Quinton Temby is assistant professor of public policy at Monash University, Indonesia and the author of Subterranean Fires, a forthcoming history of global jihadism in Southeast Asia.

Coming between the war in Afghanistan and the invasion of Iraq, but a world away from both, the 2002 Bali bombings raised the spectre of what was sometimes referred to as a second front in the war on terror.