Australia’s sad link to the wagon at the evil Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp

For many years, Sir Frank Lowy didn’t want to go to Auschwitz. But after discovering this was where his father died, he visited and after some time, came up with an idea.

When Holocaust survivor Sir Frank Lowy travels to Auschwitz-Birkenau later this month for the 80th commemorations of the liberation of the Nazi extermination camp, he expects to feel deeply emotional and perhaps even “a little lighter” for having been.

For there at the very front of the most evil and depraved gates of hell, to be seen by all the attending world leaders and dignitaries including King Charles, is an authenticated wooden train wagon used in the round-the-clock transport of one million Hungarian Jews taken to the camp to be gassed to death.

The stark appearance of the wagon on the tracks is the first of many shocking reminders of the savageness of World War II targeting the Jewish people.

But for Sir Frank it is also a place where he feels closer to his father Hugo Lowy.

“The 20th March 1944 was the worst day of my life, it marked me a certain way and the memory is so vivid and so bitter and so sad that I have lived with this ever since I was 13 years old,” Sir Frank told The Weekend Australian.

Sir Frank had spent several years scouring the world to find this transport wagon and donate it to the Auschwitz-Birkenau museum in memory not only to honour the Jews, but to be a discreet place of remembrance for Hugo, who died at the camp.

The raised platform was built by the Nazis in 1944 specifically to ensure a quicker and more productive exit straight to the Birkenau gas chambers of disorientated Jews, hungry and thirsty and gulping for fresh air having spent days crammed in the wagon without food or adequate water – often alongside the bodies of people who died en route.

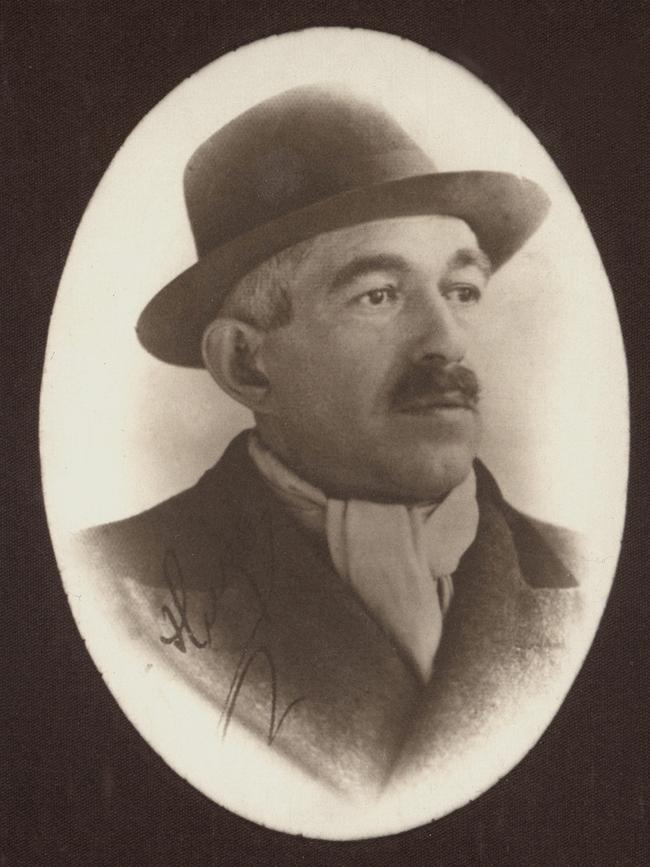

Sir Frank, now 94, had survived the Holocaust in part because of his teenage nous, but also, sadly, because his father had been rounded up at the Budapest railway station on March 20, 1944, seeking to buy tickets for the family to escape the German occupation of Hungary, which had been announced the day before.

The Lowy family had already moved once: from a tiny town in Slovakia called Filakovo and Sir Frank can remember his parents late at night on March 19 discussing having to flee from the Gestapo yet again.

But if the family had been successful in boarding the train 120km away to Veszprem, where Sir Frank’s aunt and her family were living, they too would have met the same fate as all of their rural relatives: death in a Nazi concentration camp, joining the six million Jews to have met that dreadful fate. “Had we gone we would have been deported with all those Jews never to be seen again, nobody came back from there,’’ Sir Frank said.

“My mother had four brothers and sisters and they had six children and they were deported and not one of them came back.’’

Only two of Hugo’s nine siblings survived the Holocaust.

More than 80 years later, Sir Frank can still vividly recall how he had waited on the first floor of the family’s rented Budapest apartment looking out the window and anxiously peering down the street for his father to appear after he left to buy the train tickets but hadn’t returned by lunchtime.

“I remember the angst I felt at the time,’’ said Sir Frank, wiping a tear on his face.

“The memory is deep in me, I live with this knowledge … that mark is in my heart, the loss of my father when I was a little boy.”

It would be a couple of weeks before a smuggled note from his father confirmed he had been sent to a nearby detention camp in Kistarcsa. The message had found its way to the family via a bribed guard and for several weeks Hugo and his family were able to carefully and secretly communicate, and Sir Frank’s mother even sent Hugo, who was quite pious, his prayer book and shawl, the tefillin and tallit.

And then in mid-April the messages abruptly stopped.

“There was nothing,’’ said Sir Frank. “He disappeared from the earth, we never heard from him. There were no letters, no correspondence; he just disappeared.’’

Terrified and bewildered, the Lowy family were now in a highly dangerous situation as Jews in Budapest. The family obtained forged papers which enabled the older children to get jobs as non-Jewish Hungarians. Sir Frank was listed as the illegitimate child of his mother Ilona to explain the absence of a father. Ilona worked as a housekeeper but when they had aroused suspicions and were forced to leave, Sir Frank dressed up as a messenger boy to be able to make his way through thick crowds claiming to have a telegram for the ambassador to get inside the Swiss embassy to obtain a protection visa for his mother and himself.

At the time, Swiss diplomat Carl Lutz was handing out Swiss safe-conduct documents, or Schutzbriefe, to Jewish people and the Lowys were given sanctuary, along with around 3000 others, in an international ghetto.

“The Hungarian Nazis were very brutal at the time; if they didn’t like the look of someone they just shot them. When I got the papers to go to the international ghetto under the protection of Swiss, and also the Spanish and Swedes, I said ‘Mummy we are saved’, Sir Frank remembered.

Sir Frank and Ilona survived there until the Russians came in December 1944.

“I saw the Russian soldiers with their machine guns chasing the Germans away. It was quite an event in my life,’’ said Sir Frank.

After the war Sir Frank would end up in the Israeli army, before making his way to Australia in 1952 where his sister and his two brothers had relocated.

“Australia was very good to me,” said Sir Frank who would make his way as a new migrant from delivering delicatessen items, to opening a shop in Blacktown to entering property development and jointly founding the global retail mall giant Westfield. But all that time he couldn’t find out anything about the fate of his father. His name wasn’t on any of the German lists nor the International Red Cross. His mother died in Sydney of a broken heart at aged 62, not knowing what had become of her husband.

It would be nearly half a century on before a chance encounter in California shed some light on the mystery.

Sir Frank and his beloved wife Shirley had three sons, and when son Peter was in Palm Springs in 1991 queuing to order a newspaper from hotel reception he heard an older man ahead in the queue give his name as Meyer Lowy.

The two got talking given their common surname and Peter was shocked to find that Meyer Lowy, now in his 60s, had been rounded up as an 18-year-old with a Hugo Lowy from Filakovo at the Budapest railway station all those years ago. Sir Frank, with a photo of his father in his wallet, and Shirley got on the first flight to New York to meet him. Crucially, Meyer Lowy, who had formed a close bond with Hugo, was also able to tell the family about how Hugo had died.

“When we arrived to Auschwitz-Birkenau they ordered us to get off the train and throw our parcels onto the ground near the wagon,” Meyer had told Sir Frank.

Meyer said everybody did this but Sir Frank’s father didn’t: he kept his little parcel. A soldier then forced the parcel out of his hand and threw it away but once the soldier had turned around Hugo took his parcel back.

That happened three or four times. Sir Frank said he then learned that “an SS officer came, took the rifle from the soldier and then proceeded to beat my father to death”.

The brutal manner of his death explains why Hugo wasn’t documented; he had not been tattooed with a number, nor taken to the gas chambers. Instead, Sir Frank believes his body was taken direct to the ovens in the crematoria.

He added: “The question arises what was in his parcel? What was so precious? In his parcel was a prayer book, the prayer shawl and a tefillin that mother had sent him when he was in the camp some four or five weeks beforehand.”

For many years Sir Frank didn’t want to go to Auschwitz but after discovering this was where his father died, he visited and after some time came up with the idea of the wagon to be a fitting memorial to the Hungarian Jews. It was a long search that eventually led to a German collector of wagons, who refused to take money for the wagon and donated it to Sir Frank, who paid for its restoration.

“The wagon is there on the spot where Hungarian Jews arrived in Birkenau, it is a reminder to everyone who goes there,’’ Sir Frank said.

“The name Hugo Lowy, he is memorialised, not individually, it is very discreetly done. I am kind of pleased, something of him is there and I can go, I can touch it and say a prayer and I come away a little bit lighter than when I got there.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout