She survived Auschwitz and years of communist rule — but nothing could dim Magda’s light

The wartime experiences of my in-laws, and the obliteration of an entire branch of family, have shaded each trip to Budapest, the shadows always tempered by those who survived and remained, their warmth and laughter, the jubilation of being in their embrace. Today, there is only melancholy.

Budapest is twinkling. Traders are spruiking spicy stews at the tourist-filled central market, outdoor cafe tables are full of lively diners on this autumn morning, and pedestrians are strolling the old streets beyond the Danube where cruise boats parade beneath an unusually sunny sky. Everything seems familiar. Yet nothing is quite as it was.

This day might be sparkling, cloudless and unseasonably warm, but it also feels heavy. History is personal in this city of monuments. The wartime experiences of my in-laws, and the obliteration of an entire branch of family, have shaded each trip here over many years, the shadows always tempered by those who survived and remained, their warmth and laughter, the jubilation of being in their embrace.

Today, though, there is only melancholy. After a long presence, the family’s final heart has been stilled after 103 years, and there is no one left to visit.

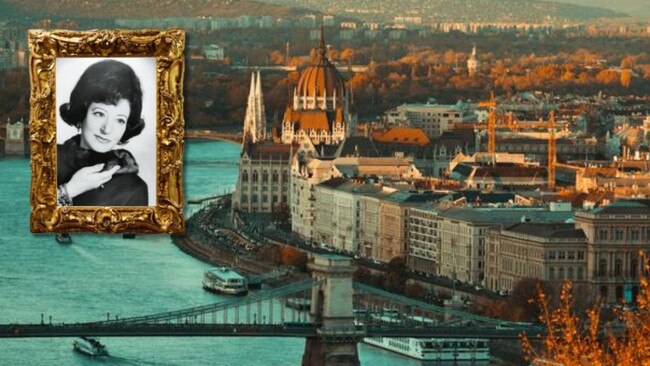

Magda, agent-in-chief of joy on every other trip, lived in the centre of this great city for much of her unexpectedly long life. A woman of silent fortitude with a passion for cakes, a flair for dancing and a distinctive guttural laugh, she was a formidable member of a generation of relatives who had once thrived on the city’s culture. She was also its last survivor.

The first time we met she was in her late seventies. Her hair was dyed a decisive black, her clothes invariably vibrant, her cheeks flush with rouge. Bejewelled and proudly manicured, on the grey streets of communist Hungary in the late 1980s she seemed the embodiment of somewhere else. As our introduction to life behind the Iron Curtain, Budapest carried a sense of foreboding, but even more there was a familial mysticism with which it was infused. My partner’s grandmother was also from this city, and she and her then nine-year-old daughter had miraculously been spared from death in 1944 when an air raid siren sounded just as they were being marched in broad daylight along Budapest’s main street, a Hungarian soldier ordered to shoot them because they were Jewish.

They managed to hide then until liberation, and after the war, having lost their father and husband and his entire branch of the family, they had restarted their fractured lives in faraway Australia.

Two aunts, Magda and Eva, had also survived the Holocaust. They, too, had remarried, but their husbands were locals, and in Budapest they remained.

In the ensuing decades there were regular letters and occasional long distance calls with their sister in Australia, who even managed to visit a few times. Otherwise these two ageing women remained on the other side of the world, alive but absent in a country they could hardly leave, the distant and final traces in eastern Europe of an almost obliterated family.

And then there they were on a late summer’s day in the 1980s. Waiting to greet us at a Budapest cafe, both were resplendent in the tailored clothes they had managed to amass in a market that discouraged individuality, smelling of powder and perfume, beaming and cooing over us in a language we could not understand. Eva, two or three years the younger, was blonde and demure, sweet, warm and adoring. But it was Magda who captured the room, with her husky voice, her easy chatter and her deep laughter.

Both women were dressed impeccably when we met at that charming cafe which, like the sisters, had deftly navigated the restraints of communism. As besuited waiters covered the marble-topped table with coffees and slices and dainty glasses of water, the aunties seemed almost regal with their solid postures, coiffed hair and perfectly applied lipstick, and they walked carefully but elegantly in their dainty shoes as they later led us along so many alien streets.

Apart from love, we had no common language. They had only a smattering of English, while Hungarian proved as notoriously tricky to master as we had been warned. The best possibility was German, a language that both sisters had apparently mastered to survive their unspoken wartime histories and were reluctant to remember. My knowledge was limited to episodes of Hogan’s Heroes. But it was our only option. Over the following days we amassed a German lexicon that included “piano”, “expensive”, “nice” and “wedding”, and with this unlikely set of words joined the sisters on an exploration of their city, along its old streets with their strange Soviet-era cars, and everywhere the pungent odour of the capsicums so beloved in the local cuisine.

Not always sure where we were headed or what was being said, we followed them through a maze that seemed familiar yet distant to them, past the faded apartment building where their sister and niece had lived long before their departure to Australia, into the cavernous courtyard and right up to the enormous double front doors that now opened on to other people’s lives. There was the old convent where their eight-year-old niece had briefly found refuge mid-war, and the school her mother had attended in a happier era.

At each building the sisters paused solemnly, and we would take a precious photo on our sole roll of film, whose contents, developed weeks later in the West, recorded them standing proudly with their hair high and teased, wearing tailored suits with their shirt collars sitting just so. Somehow, through our disjointed conversations, we realised that in 40 years they had rarely revisited these nearby streets, which were still loaded with memories but which they also felt compelled to show us.

History was here, and it was personal, but it mattered only so much to us then. The language barrier, and possibly our youth, meant we wondered little about the sisters’ pasts, and their experiences of the Holocaust. And even if we had, a short visit didn’t seem the right time to ask. So we walked, we ate, we delighted at being in their presence in their city. And somewhere in the muddle of what constituted our conversations, Magda mentioned something about growing up with Zsa Zsa Gabor.

Our children joined us on the second visit. A new millennium had arrived and Budapest was busier, shinier – and capitalist. The scent of capsicums was gone, replaced by the indifferent aroma of so many other cities, and on Budapest’s busier streets the unreliable Trabants and Ladas had been usurped by familiar Western cars. On the drive from the airport, huge new billboards advertised everything that had been banned or unavailable last time.

Eva was ill, so we spent most time with Magda, who was now over 90 and widowed for a second time. Her apartment, with its picture window facing the blooming horse chestnut trees outside, became the focal point of our small family gatherings. We snacked on sweets around the low table in her darkened living room, where the heavy drapes brought a pall of European air even on the sunniest of days.

Capitalism had wrought some obvious changes to Magda’s life. She had managed a trip to Vienna in the early months of Hungary reopening to the West. And on a small table in her back room sat a desktop computer, on which she often played games of solitaire. Otherwise her apartment remained a time capsule of old Budapest, from the well loved rugs on the wooden floors to the cupboards in her tiny kitchen so crammed with old crockery sets that the doors had to be taped shut.

Now living alone, Magda had become less self-reliant over the intervening 20 years. With her children and grandchildren living overseas, a receptionist from her doctor’s surgery checked on her most lunchtimes, when she would also enjoy a hot meal from a nearby restaurant. But she still laughed frequently and with gusto, through emails to Australia she seemed up to date with even the most mundane details of our lives, and her joie de vivre was still impressive. One day on a whim she led us down the oversized stairs of her building in her elegant heels, and out to the street. At her favourite cafe she selected a song from the jukebox and spent the next hour dancing with our children to Elvis Presley. On the return walk, they jostled for rights to cling to her arms.

Observing this merry group, I wondered at Magda’s warmth and fortitude, a childhood intermingling with Zsa Zsa Gabor and her sisters, the decades she had lived here without any family, the memories she must have carried since appearing on the family doorstop in this city one day in 1945, announcing her presence and then fainting – a belated confirmation for her few surviving relatives that she had miraculously returned from Auschwitz.

But the lack of a mutual language was still a barrier, and now she was even older and it seemed harder to start asking questions. So I left her in the thrall of a younger generation who seemed less perturbed about the language gap – or about the past that had fashioned this matriarch beside whom they were happily skipping down the street.

When we next met she was 102. Eva had died and, apart from the small group of carers who tended to her, Magda was alone in her city. With 36 hours to spare during a work trip to Europe, I contacted one of her helpers and arranged to visit. I entered that familiar unit, up the heavy stairs to the front door with its multitude of locks and down the dark corridor to the living room where she sat in a brocaded armchair as though a week, and not almost a decade, had passed since our last hug.

One of the carers had invited an English-speaking friend to translate, so for the first time we could converse. Over the hours that followed we talked about the mayoral visit on Magda’s 100th birthday and the generations of family she knew of but had never met in Australia. Finally I could even ask her about Zsa Zsa Gabor. (“That harlot,” she guffawed before explaining, with great hilarity, how she and her sisters would be locked up by their mother whenever young Zsa Zsa arrived at their doorstep to buy jewellery from Magda’s father’s business.) One of the carers summoned a photo of Zsa Zsa on her phone and Magda was chuffed when we agreed she had aged much better than the Hollywood star, who, she insisted, was several years older than she claimed.

In her 11th decade, Magda was still effusive, and thanks to the rapid translations, she appeared even more spirited than our mix of hand gestures and pseudo-German had previously suggested. But physically she was flagging. As she rarely left home, there were no more cafe visits. She tired easily, and after a few hours of laughter I left her to rest.

When I returned that afternoon, I wondered again about delving into her past. But there were only hours remaining until my train departed, and even with translators on hand it seemed impossible. How do you ask a 102-year-old woman to tell you her war history when you’re in her town for one night only?

As the sun lowered and that final day with Magda inevitably ended, we hugged one more time. Her cheek was soft and familiar as we kissed goodbye. I don’t remember if I turned around at the front door, but I remember staring at its multitude of locks on the slow walk past and realising I would never see them again.

Budapest is beautiful when I return in late 2023. The climate, like so much else, has changed markedly and on this mid autumn day, instead of a brutal wind or even snow, the city is experiencing summer-like warmth.

Magda died a year or so after my last visit. She was 103. Soon after, I began researching other people’s Holocaust histories. I wrote articles and published a book and I can tell you in great detail about the experiences and outlooks of so many other survivors. But not about Magda.

In her old city, the silence of her past feels as mournful as her absence. In homage, I walk down her street, along the block where our kids had clung to her, near the cafe where they had danced, past the restaurant that had cooked her daily hot meal, and up to her building, which is sturdy and familiar and now also foreign.

The facade is the same, the paint is still fading, but her name has been replaced on the panel at the front door, and in the window of her old lounge room a bright, modern curtain flaps in the sudden breeze.

In the tiny crypt where her remains are interred, she is remembered simply as “mother”. But standing in that marble space in a Budapest cemetery summons nothing of the woman I remember. So I end up in a cafe in her old neighbourhood, thinking that coffee and cake might be the sweetest toast of all.

The place with the jukebox seems lost so I settle for the oldest looking cafe I can find in the area, thinking she had probably spent time here. I sip a latte and silently toast good memories, and only when I pay does the owner proudly reveal that it is actually a new establishment, opened only for months, and that he has carefully furnished it with old pieces.

Throwing together a bit of this and that, he has recreated a world that, I finally realise, is gone. b

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout