Amplified calls for greater awareness of mental health

It has been another sad week for the AFL. Another well-known former athlete suddenly passing has once again amplified calls for greater awareness of mental health, particularly for men, who are disproportionately higher in statistics of suicide.

Former athletes, mental health advocates and medical professionals are collectively appealing to the AFL to highlight the issue through a “mental health round”.

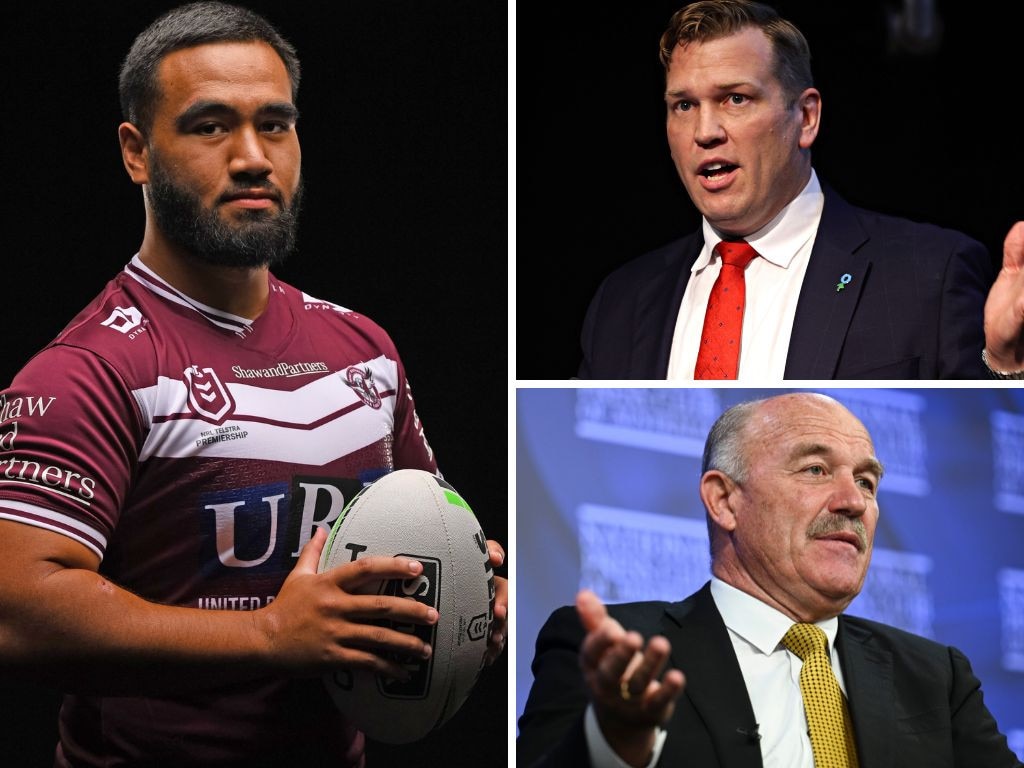

The AFL, and NRL, have created specific matches to highlight the issue of men’s mental health, specifically “Spud’s Game” in the AFL and the Paul Green Medal in the NRL, but calls are being made to designate an entire round to focus on mental health.

Yet a fundamental issue is being continuously ignored, particularly when tragic deaths have been leveraged for highlighting an issue that was central to the deaths of Danny Frawley, Green and others such as Shane Tuck and Heather Anderson, who also passed too young.

Frawley, Green and others did not suffer from “mental health issues”.

Frawley suffered from a degenerative brain disease we know as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE.

As reported in The Australian on Saturday, the science from international research is becoming clearer. CTE risk is associated with exposure to many repetitive head impacts. Many former players are revealing their ongoing issues that while affecting their mental health, it does not go the root of their problems faced on a daily basis.

In my 16 years of researching sports concussion and CTE, and publishing dozens of scientific papers and talking to players and their families, a common theme remains constant; it is not simply a case of “mental health issues” but rather trying to deal with “a broken brain” (that is the only way athletes and their families can explain it).

On a daily basis, I will get messages from people who tell me that many, including medical and health professionals, still do not know what CTE is.

Given the publicity around concussion and “its protocols”, it is concerning but not surprising, because given our obsession with these sports, CTE is not widely discussed.

Let’s be clear: CTE is rare in the general population, but the risk of suffering CTE is higher for those who have been exposed to repetitive head injuries – not just blows directly to the head but those received indirectly from bumps, tackles, and other physical impacts experienced in contact sports.

Let’s also be more clear: not everyone who plays contact sports will get CTE, just as not everyone who smokes will get cardiovascular disease, or those who lie in the sun will get melanoma.

But the risk is greater.

The research from the US, Britain and my own recently published studies have shown that the risk is not related solely to concussion.

The mathematics shows that the longer time and the more exposure to repetitive head impacts an athlete receives, the greater the risk.

This is more than just a concussion issue.

Concussion is a brain injury, not just a “head knock”, and it may have serious long-term after-effects.

Indeed, there is good evidence that concussion is a risk factor for mental health.

However, CTE is a progressive brain disease. While individuals at the time will not notice any symptoms, CTE develops in early adulthood.

Symptoms that manifest in mid-adulthood include anxiety and depression, anger and irritability, impulsivity, poor sleep, and suicidal thoughts or actions … symptoms that significantly overlap with “mental health” problems.

Yet after five years of “Spud’s game”, where addressing men’s mental health is placed front and centre before and during the game, the real disease underlying Frawley’s problems, CTE, has virtually never been mentioned. We cannot afford to simply “mental health wash” CTE.

I appreciate that when a former athlete (professional or even local club level) has mental health concerns, or passes away suddenly, that jumping to any conclusion is irresponsible and reactionary.

And I do not want to be mistaken for disparaging the mental health crisis in society today, as the issue is much needed to be continually addressed.

However, when a player is posthumously diagnosed with CTE, we should not simply ignore the facts, particularly when many retired players, and their families, today are calling for more acknowledgement.

The ripple effect of a player dying from a preventable brain disease linked to sport is profound.

It is possible to balance our love of contact sports and reduce the risk of CTE, but it takes political will of our sports, and the challenge of the wider public to accept that change is necessary.

And it is more than just “concussion protocols”.

As CTE risk is linked to repetitive head impact exposure, we need to modify our approach to training. Already in rugby union, contact training is limited to 15 minutes a week and the standard has not seemed to suffer. We have yet to implement similar strategies in AFL or rugby league, despite calls from the Victorian coroner following cases of footballers with CTE.

We also need to modify our sports in children and young adolescents with non-contact versions of games until the age of 14 years. This can reduce six to eight years of potential exposure.

We accept modifying sports and place limits for kids in other games to reduce the risk of chronic injuries.

We can do the same to reduce kids getting hit in the head. At 12 to 14 years of age, they can learn in a controlled environment how to tackle and be tackled properly.

The Australian’s story on Saturday continues to highlight the plight of our past players who sustained tens of thousands of head impacts that they received playing the sport they loved for many people’s entertainment.

The sports must be brave enough to examine and acknowledge the past in order to find the best way to protect future generations from the risk of CTE.

Starting to at least formally acknowledge that CTE is a real disease and to acknowledge CTE and support the science at events like “Spud’s game” will be a start. Acknowledging CTE will also significantly advance mental health outcomes but more importantly, it will accurately honour the memory of our beloved athletes and their families.

Alan Pearce is an adjunct professor at Swinburne University of Technology. He is also a co-founder and non-executive board member of Concussion Legacy Foundation Australia