A backyard? We all should be so lucky

The great Australian backyard is no more, a casualty of sky-high property prices and the reluctance to step outside the home.

The great Australian backyard is no more, a casualty of sky-high capital-city property prices and the reluctance of families to step outside the comfort of home.

Backyard cricket, gardening and the simple pleasure of playing with the kids has given way to super-sized houses and the demands imposed on weary parents by long days at work and slow capital-city commutes.

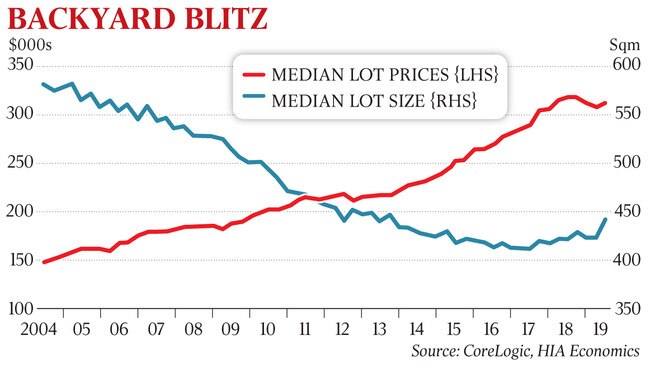

New data from the Housing Industry Association, provided exclusively to The Weekend Australian, reveals that the traditional quarter-acre block of 1000sq m is fading fast from the urban landscape, with the median home lot now a skinny 441.2sq m. In new developments on the Sunshine Coast and in Perth, houses are being built on as little as 80sq m.

The cost of residential land has exploded since the turn of the century, from $327/sq m in Sydney in 2001 to an eye-watering $1047/sq m today, down slightly on the peak two years ago of the city’s benchmark property market.

More Australians than ever are choosing to live in units and townhouses. A decade ago, only 12 per cent of new homes were apartments; that proportion has now grown to 30 per cent and was set to rise further, said HIA chief economist Tim Reardon.

“There is a demographic shift away from the traditional house-and-land package,” he said. “Workers in metropolitan areas aren’t going to shift out of apartments in the city and relocate to the fringe in order to purchase a new home.

“They will increasingly populate the middle-ring suburbs that are still within commutable distance of the city, which is where they’re likely to work and are liable to provide some form of garden or backyard amenity, even a shared or common garden.”

Making more of less outside space is the name of the game for families that still want it all: a renovated house with two or more bathrooms, individual rooms for the children and a yard that can accommodate a cricket game or a kick overlooked by the al fresco dining area.

The Barnes family’s backyard in Ingleburn, southwest Sydney, is squeezed into a 430sq m lot and boasts a sunny deck where parents Angie and Jake can keep a wary eye on what Rylan, 11, and Jade, 6, are up to. Ms Barnes, 31, who is nursing four-month-old Gracie, said the family hoped to eventually trade up to a bigger property with more outdoor space.

“I’m forever kicking the kids outside,” she said. “It’s school holidays, so they are always out there. If they weren’t, they would be inside on their devices.” However, the demise of the traditional backyard can be counted in the cost to children’s mental and physical health, and urban “heat islands” that have far-reaching social and equity implications, experts warn.

The Stockland group, one of the nation’s biggest developers of masterplanned urban-fringe estates, has incorporated into its new Edgebrook project in Melbourne’s outer southeast a purpose-designed park for autistic children.

Other home builders are transporting the shared entertaining spaces, pools and communal gardens offered in inner-city apartment living to the low-rise suburbs, along with innovations such as exclusive-use dog parks in lieu of a backyard.

In a special series launched on Saturday, The Weekend Australian examines how this shift is affecting the quality of life of the 68 per cent of Australians who call a capital city home.

The HIA’s snapshot of the Australian backyard shows it to be a shadow of the grassy hub that dominated family life for generations when the quarter-acre block held sway. By 2001, the median capital city land lot had shrunk to 606.7sq m, falling to 469.7sq m in 2010.

Brisbane experienced the sharpest decline in lot size over the past three decades, shedding 280sq m off the median of 702sq m in 1991, to 422sq m for the June quarter last year.

Over the same period in Melbourne, the lot size went from a median of 646sq m to 501sq m. But the price of residential land in the Victorian capital has increased by a staggering 394 per cent this century, rocketing from $139/sq m in 2002 to $797/sq m on the HIA breakdown.

The cost of home lots climbed 323 per cent in Perth between 2002 and last year, 310 per cent in Adelaide and 306 per cent in Brisbane. But Sydney remained in a class of its own after the median price surged through the $1000/sq m mark four years ago.

Corporate demographer and columnist Bernard Salt said Australians had shunned the big backyard due to the expense and a reluctance to commit time to maintaining a lawn and garden.

A product of the quarter-acre block his parents had in Terang, country Victoria, complete with vegetable patch and chook shed, he said the backyard no longer suited fast-paced urban life. “The backyard is a vehicle — it’s plastic, pliable and it’s changing. We … mould it to fit the aspirations of this generation,” Mr Salt said.

Psychologist Rachael Sharman, who has researched the link between exposure to the outdoors and nature to mental wellbeing, said time in the backyard or a park had a therapeutic value equivalent to medication for some children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

But Steve and Estelle Hunt found that their acreage on the Gold Coast hinterland was too much to handle with the demands of two children and running a business. So they moved to an apartment at Burleigh Heads and made the beach their backyard.

“We lived on two acres with a four-bedroom house, a pool and plenty of land,” said Mr Hunt. “We both worked in our busy business and it was taking 20 minutes to trek into the city each day. It ate into our weekend.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout