Beyond our suburban backyard

The sprawling suburban idyll is a victim of our modern lifestyle.

So many of us trace our earliest memories to that bygone time in the backyard or pine for the suburban idyll it represents. The quarter-acre block, 1000sq m of dirt to scrape knees and fire children’s imagination, where there’s lawn to mow, nooks to explore, space to grow, is a touchstone of Australian life, the cradle of simple pleasures and wide-eyed innocence we remember with a wistful smile.

Australians of a certain age will recall daylong games of backyard cricket with the kids from next door and across the street; Dad pushing the Victa, Mum tut-tutting after the beetles got into her tomato vines again. Everyone knew the rules: tip and run, six and out if you didn’t keep the square cut on the deck.

When it was too hot or wet to play, we would shoot marbles until our thumbs hurt. No one complained about being bored because you could bet a grown-up would swoop. Bored, eh? Something always needed doing: a hose for the lemon trees, weeds dug in the vegetable patch, the Falcon washed. “The compost heap won’t rake itself,” Nan would say.

The chooks lived in a pungent shed by the side fence. One of the dogs would usually try it on, creeping behind us when we went in every morning to collect the eggs. On fine evenings, Dad would fire up the incinerator after he arrived home from work. We would all stand around and clap as glowing embers erupted from the chimney pipe and danced away into the gathering night.

In time, we yearned to escape, too. Our horizons had broadened beyond the backyard — the enduring wonder of growing up in this luckiest of countries, the big, bleached summer sky a portent of the opportunity that was sure to come our way.

Ah yes, those were the days.

Now look around where you live. Some things haven’t changed. Nearly 80 per cent of Australians still dwell in detached homes, mostly in the sprawling suburbs that make our cities among the largest in the world by land area. A love affair with the car is undiminished, with motor vehicle registrations hitting 19.5 million last year, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, giving half of all households access to two cars or more.

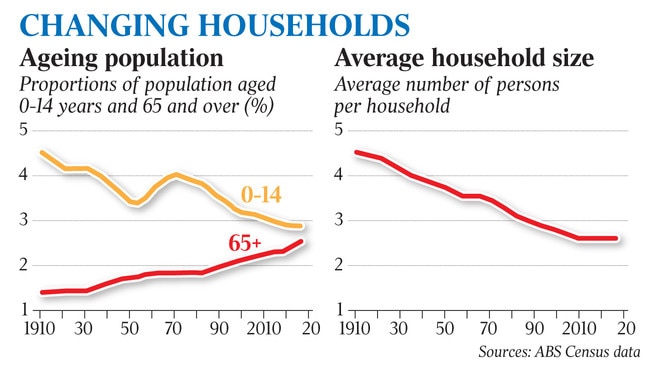

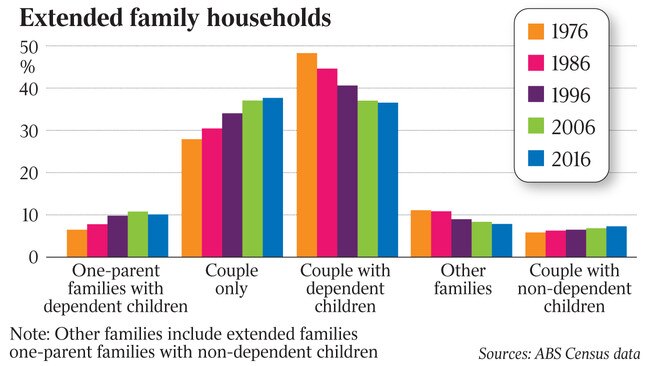

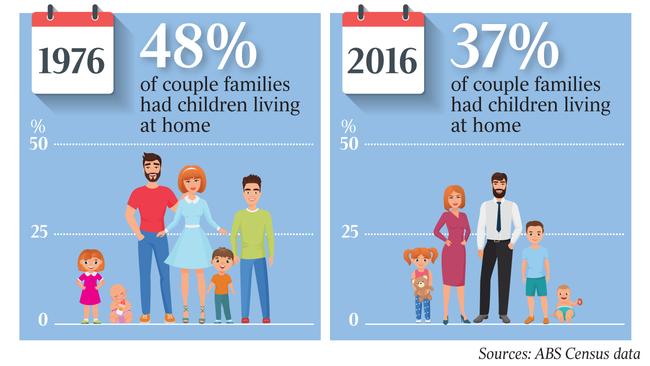

Families continue to make up 70 per cent of households, though these have shrunk from an average of 4.5 people in 1911 to 2.6 at the 2016 census. The average home is bigger, better and more lavishly equipped, boasting multiple bathrooms, perhaps an AV room, probably a parents retreat, for an average of 186sq m of inside area. Australian houses are second in size only to those of Americans.

The backyard, however, is unrecognisable, sliced and diced to a shadow of what it was when it commanded centre place in family and community life. The traditional 1000sq m block was cut in half through the 1980s and 90s, and in new developments the norm is more like 300sq m, barely enough to squeeze in a pool and an alfresco area behind the super-sized house that takes up nearly every other metre of space. Micro home lots of barely 80sq m have hit the market on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast and in Perth.

Spiralling urban land costs — which account for at least two-thirds of a property’s monetary value — are driving this shift. The planning imperative to check the expanding footprint of the east coast capitals is another factor, ostensibly to ease the expense to government of servicing a far-flung metropolitan fringe and to make better use of land near the CBD, where public transport, hospitals, schools and other social infrastructure are clustered.

But the real difference is how Australians aspire to live. The backyard is a victim of the modern, cosmopolitan lifestyle embraced by a nation of city dwellers who perversely want less and less to do with one another.

As corporate demographer Bernard Salt points out, the quarter-acre block in the ’burbs that seemed like heaven to the great-grandparents of today’s millennial generation, emerging from the 1930s Depression and crowded inner-city terrace housing, had lost its cachet by the time baby boomers born between 1946 and 1964 were ready to leave home.

“At the end of the day we are reinventing how we want to live,” says Salt, managing director of the Demographics Group. “The suburban backyard as we know it in an iconic sense, with kids with skinned knees and playing cricket, that was truly liberating and a wonderful quality of life for the post-Depression generation.

“But to us, two generations on, it just looks a bit daggy. It looks inefficient. It is committing sins against the environment. It needs to be purified, cleansed, reimagined to reflect our values. The backyard is a vehicle — it’s plastic, pliable and it’s changing. We … mould it to fit the aspirations of this generation.”

As reported in the news pages of this paper, new figures from the Housing Industry Association chart the demise of this mainstay of the great Australian dream. Since 1991, capital city home lot sizes have contracted by up to 30 per cent, to a median 441.2sq m. The sharpest drop happened in Brisbane, where 300sq m was carved off the average block. Median lots sizes in the benchmark Sydney and Melbourne markets fell to 454sq m and 501sq m respectively.

Prices, of course, still rocketed, with the NSW capital leading the way. Residential land that sold for $327/sq m at the turn of the century in Sydney had hit $1047/sq m by June last year, slightly down on the eye-watering peak of $1198 recorded before the market eased. Because prices in the other capitals were coming off a lower base, the increases have been even more striking: 394 per cent in Melbourne since 2002, 326 per cent in Perth, 310 per cent in Adelaide and 306 per cent in Brisbane, the HIA breakdown shows.

Small wonder that backyard size has slipped on buyers’ priorities, especially for first-timers struggling to break into the market. And we’re all uber-busy, right? As much as the idea appeals, who has the time to look after a garden or the spare cash to call in the mowing man?

Encapsulating the trend, urban planning expert Tony Matthews of Brisbane’s Griffith University says: “A lot of city people are happy to sacrifice a large backyard because it buys them a couple of hours at the end of a week devoted to slow commutes and long days at work. There’s a confluence of factors … an economic element, a planning element from the viewpoint of government and local authorities trying to save on service outlays and a strong consumer preference in the big cities where an overwhelming majority of Australians live.”

Altered work dynamics, with women juggling parenting with a paid job and more stay-at-home dads, reinforce this. “You’ve got a younger generation where typically both partners work as compared to the 1980s and 90s,” says Connie Kirk, national executive director of the Urban Development Institute of Australia. “So, for them, a backyard isn’t necessarily something they want because they think it is yet more cost they have to incur and maintain.”

Do today’s property buyers appreciate what they are giving up? The benefits of a backyard are harder to quantify, but no less important in terms of lifestyle, amenity, social cohesion, health and wellbeing. And as it turns out, the architects of sleepy suburbia might have been on to something.

Let’s start where we all do, with childhood. The physical dividend to kids of having a backyard, if only to entice them off their devices, has long been recognised: active children are fitter and healthier, and with Australians ranking near top of the world in the waistline stakes, the earlier good habits are inculcated the better for all concerned. According to the 2016 National Health Survey, 65 per cent of us are overweight and 29 per cent obese, double what was registered in 1995.

For the Clarksons of Brisbane, this consideration trumped all else, even renovating their high-set Queenslander in Coorparoo in the city’s east.

Instead, parents Mark and Helene pumped $24,000 into the pocket-sized backyard, transforming it into a playground with a cricket pitch, basketball key and soccer goal for their boys, Zak, 16, and Harry, 10.

“We were latchkey kids,” says Clarkson, 49, a part-time office worker. “We would run around all day and our parents would only hear from us when the street lights came on. This feels like that again.”

Psychology researcher Rachael Sharman says study after study has shown that “vitamin N” — for nature — is equally crucial to mental wellbeing. Given that an estimated 80 per cent of forest cover in an Australian city is on private property, the precipitous decline in backyard space has health implications that are only starting to be appreciated.

Broadly, access to nature has a proven calming effect on people, lowering blood pressure and anxiety levels. Sharman, of Queensland’s University of the Sunshine Coast, cites US research documenting how a walk through a nature area or park can match the therapeutic benefits of medication for some children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

“To be perfectly simple, it just calms their farm,” she tells Inquirer. “We don’t fully understand why that is the case but what we know is that kids who play outdoors regularly and have access to nature show a whole raft of physical and psychological improvements.’’

A Canadian study, summarising the various benefits turned up by international research, found that contact with nature can restore the ability of adults to pay attention and speed recovery from illness. It may even reduce the risk of early death.

Developers have caught on. The Stockland group, a big masterplanning exponent, has incorporated a “sensory park” into its Edgebrook community project in Melbourne’s outer southeast designed to help children with autism spectrum disorder. It has calming water sensory zones, quiet spaces and themed zones to help kids challenged by sensory process, social interaction and movement.

While applauding clever use of scarce space in the nation’s growing cities, Sharman warns it is no replacement for the traditional backyard, especially where children are concerned.

“I can understand why people don’t want a backyard,” she says. “There are probably some lifestyles that don’t sit particularly well with looking after a garden … you know, 90-year-old nanna might not want to push a lawnmower and a professional couple working long hours could probably think of better things to do with their spare time.

“Where it becomes problematic is when you insert children into that environment — say in a townhouse or unit or a home with limited outside space. The literature and, I think, our life experience tells us it is not conducive to good child development. You are offering a style of housing that is less and less child-friendly in Australian cities, and my broad message would be that withholding those experiences of nature and outdoors play from children is really quite damaging. We need to reconsider.”

The unintended consequences can emerge in the most unexpected places.

Take mainstream professional sport. Young players pushing into the elite ranks of cricket or the various football codes are generally faster, stronger and fitter than ever thanks to sports science and all those hours in the gym. But coaches are noticing that intuitive ball skills, spatial and game sense increasingly have to be instilled, a product of the disappearing backyard.

Rugby league great Steve Renouf, 49, has tracked this through the years. “Look at backyard cricket,” he says. “The skills kids learned playing that can be taught later but it’s not quite the same, not as instinctive. In footy, there’s a lot you pick up as a kid around spatial and game awareness by playing in the backyard.”

Wallabies legend Paul McLean, 66, agrees. “I learned to kick a footy well before any formal competition,” says the champion rugby union back and Rugby Australia director. “The point of difference between the top players, especially in rugby, is the intuitive stuff that can’t be taught.”

Townhouse torment

Keep looking around where you live. If it’s an inner or mid-belt suburb, chances are you are all too familiar with the process of urban consolidation. The outward expansion of unit and townhouse developments from the CBD testifies to that.

The principle was sound enough, articulated from the early 1980s in programs such as the Hawke Labor government’s Building Better Cities initiative, which set out how town planners should maximise existing infrastructure close to the urban heart by “infilling” — increasing housing density in established suburbs largely devoted to detached housing.

The result was a boon for savvy owners of traditional 1000sq m home blocks who subdivided or sold to developers. But one of the unforeseen consequences has been to create “heat islands” of bitumen and concrete in formerly leafy areas, a growing concern for communities and government.

Former town planner Jason Byrne, now a professor of human geography and planning at the University of Tasmania, says built-up areas of Australian cities can be up to 8C warmer than the surrounding countryside, such is the heat island effect. Ecologists are tracking a range of environmental impacts, including the “overwintering” of migratory birds that stay put for weeks longer in the city.

People who don’t have airconditioning lose sleep on hot nights and those who do feel the pinch of higher power bills. “Reduced sleep has an impact on mental health,” Byrne says. “People become more irritable, more prone to outbursts, which has social implications. This can also be a precursor to anxiety and depression.

“In Australian cities the more affluent areas tend to be on the water — beaches, the harbour or river — and are cooler on hot days. In western Sydney, we’ve seen 45C temperatures this summer and there is an argument that people there could less afford to run aircon, even though they arguably need it more. You would find similar examples in most capitals.”

Belatedly, state and local authorities are putting in measures to protect the backyard. In Victoria, Daniel Andrews’s Labor government has mandated that new home lots of 400sq m to 500sq m have 25 per cent of the space set aside for gardens, rising to 35 per cent for those of more than 650sq m. This is linked to an updated Plan Melbourne, a blueprint designed to preserve the city’s “neighbourhood character”.

Brisbane City Council, the country’s largest covering 1.2 million people, has gone even further, banning townhouse development across nearly 63 per cent of the municipal area zoned for residential use. This has angered developers, who complain it defies the logic of urban consolidation, but BCC chairman of city planning Matthew Bourke is unmoved.

“We have seen what has happened in some other cities where owners have amalgamated their land and put it on the market for sale for townhouse development,” he says. “We don’t want to see large-scale projects like that in our established suburbs … it fundamentally changes that community, and the feedback from residents is they don’t want it.”

Adam and Kerri McKinnon felt trapped in the suburbia of Broadbeach Waters on the Gold Coast: the house was nice enough but after Jayde, 14, took up horseriding with her mother, their priorities shifted. They moved to acreage at Tallebudgera where there’s enough space to accommodate everyone’s interests. “From my perspective, in the suburbs, the house was just somewhere we lived. The girls were out with the horses, and we boys at sport,” says Adam McKinnon, 50, with a nod to son Lachlan, 12. “We would only see them late at night. Now our property is what we do.”

Six and out no more

Salt says the evolution of the backyard has tracked the shifting social and economic forces that shaped modern Australia. The rollout of sewerage infrastructure allowed the unplumbed toilet to come indoors — though it was a long wait for some cities, such as Brisbane, where the work was not completed until the 70s. Improved garbage collection and pollution controls put paid to the incinerator, the supermarket to the chicken coop.

“The backyard has always served a purpose and that purpose has changed over time,” Salt says, harking back to his childhood in a housing commission home in Terang, country Victoria. “I grew up on a traditional quarter-acre block and we had an incinerator, compost heap, wood pile, enormous veggie patch, fruit trees, a chook shed … I don’t think Mum ever bought eggs or produce. It was like a self-sustained community.

“But pressure for efficiencies, the cost of land, changes in how we work and what we want in housing mean we don’t live like that any more. It’s easier to buy our food from the supermarket or have it delivered prepared; the old Hills hoist clothes line took up too much space, so it’s largely gone, reduced to a fold-down version or we use the dryer inside.

“Our homes have doubled in size and they now encroach on the edge of the block. You don’t tend to know your neighbours these days or have the kids next door hanging over the back fence. That was cultivated in the 1950s and 1960s because mothers were at home, they could chat to each other, there was a real community and kids were in each others’ houses.

“Today, kids are more likely to have structured playdates. They might be driven to indoor cricket on Tuesday and do Gymbaroo on Wednesday. The informal, make-it-up-as-you-go games of the backyard have been sanitised and regimented into other parts of the day.”

When he thinks about the modern backyard — small, neat as a pin, the kids’ clutter packed away — Salt says he envisages walking past a designer bedroom, the pillows plumped invitingly. “It is taking the house outside … the backyard is really another room to be admired,” he explains. “It has an alfresco place, a barbecue with a wok burner. And if you want that vista value, then you don’t want a cricket pitch there, do you?

“You can’t have all the paraphernalia of kids or, if you do, it’s got to be screened off so the adults can enjoy the view. The whole purpose of the backyard has changed from utilitarian, from a cultural mix where kids learned freestyle play and arrangements with bruised knees, cuts and all the rest of it, to an area with half the space at best, far less utility, a place to be admired from afar and not messed up.” No dirt, no six and out cricket shots, no fun. Yes, we’ve come a long way.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout