Timor-Leste artist Maria Madeira’s potent, political exhibition

Venice Biennale this year welcomes the inaugural pavilion from Timor-Leste, featuring a powerful and poetic work by an esteemed contemporary artist that shines a light on the suffering and bravery of her fellow countrywomen.

Every two years Venice morphs into the centre of the art universe as La Biennale di Venezia takes over the canal city. The biennale, often dubbed the Olympics of the art world, is a showcase of the globe’s best contemporary art, arranged in national pavilions funded by governments and private philanthropy. The VIP vernissage is populated by a who’s who of artists, curators, critics, celebrities and discerning collectors desperate for a first glimpse.

La Biennale di Venezia is a career pinnacle for artists chosen to represent their country. In 2024, the exhibition’s 60th year, it features 330 artists, the vast majority of whom are First Nations people. The theme is “Foreigners Everywhere”, and under the curatorial direction of Adriano Pedrosa, looks to the broader diaspora, focusing on ideas of migration and exile.

Jeffrey Gibson makes history as the first American-Indian queer artist to represent the United States; Ghanaian-born video artist John Akomfrah is representing Great Britain in a nod to that nation’s colonial history, sponsored by Burberry, no less.

The most coveted accolade at the biennale is the Golden Lion. This year, Indigenous artist Archie Moore, only the second First Nations artist to represent Australia,

was awarded the Golden Lion for Best National Participation for his beautiful work, kith and kin, curated by Ellie Buttrose. Moore is the first Australian artist ever to win. There was much jubilation.

Aotearoa, New Zealand-based Mãori female Mataaho Collective was also awarded a Golden Lion for participating. It was a collective antipodean triumph, unexpected and overdue. Although most of the biennale action occurs in the Giardini (public gardens) and the Arsenale di Venezia (the former shipyards), art sprawls across the city, overtaking small churches, scuole (schools) and private palazzos. These off-site exhibitions often contain hidden gems, such as this year’s inaugural Timor-Leste pavilion, another astonishing biennale first, showcasing the work of Maria Madeira, perhaps Timor-Leste’s most significant contemporary visual artist.

Maria Madeira: Kiss and Don’t Tell is a stirring work curated by Natalie King that shines a light on the 24-year brutal and bloody occupation of East Timor, as it was then known, by Indonesia. The period was marked by torture, disappearances, sexual slavery and massacres.

Madeira now lives between Timor-Leste and Perth, where she migrated in 1983 after spending seven years in a Red Cross refugee camp near Lisbon in the wake of the Indonesian invasion in 1975. The artist’s thoughtful, engaging practice is informed by personal traumas and her deep love for her country, and she is a prominent figure in Timor-Leste’s struggle for independence, all while attaining several degrees, working as an art teacher in Australia and Timor-Leste, and achieving a PhD.

This milestone exhibition in Venice, commissioned by the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, coincides with the 25th anniversary of the end of Indonesian occupation.

If Madeira is a first-timer, King is a biennale expert. The esteemed Australian curator, writer, editor and enterprise professor at the faculty of fine arts and music at Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne was curator of Yuki Kihara: Paradise Camp, Aotearoa New Zealand in 2022 and curator of Tracey Moffatt: My Horizon at the Australian pavilion in 2017.

The powerful pairing came about after King received a mysterious phone message asking her to call art dealer Anna Schwartz. “She said, ‘I’ve got a project I’d like to discuss with you: taking Maria Madeira to the Venice Biennale’. As soon as I saw Maria’s poetic work, I knew it was political and urgent, and I had to be part of this triumphant undertaking within a very compressed timeline. We were only contracted in January, and the lease was signed at our venue.”

Madeira agrees time was of the essence. “Because Anna Schwartz believes in my work, she wrote to [Timor-Leste] Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão to say she thought it would be great if Timor-Leste could be part of the Venice Biennale and proposed me as the representative. Then, the theme of the biennale suited my work, and I knew exactly what I wanted to show. It’s like the stars aligned, and here we are.”

“Venice Biennale is the world’s oldest and most prestigious visual arts event, started in 1895. In my opinion, the sheer scale of the audiences that come, the discourse that emanates, and the cross-section of artists make it one of the key moments on the calendar,” says King.

Despite the short time frame to prepare for an event of such a significance in the global art world, King says the team rose to the challenge. “We scaled up quickly, and Maria just seemed to spin people into her enchanting aura, and miracles happened. Maria’s project involved singing and performing Kiss and Don’t Tell.

We wanted to produce a film version that narrates the painting installation because the performances only took place during the opening week. Anna called film director Robert Connolly (The Dry and Balibo), and Maria sang with an entire crew, and we filmed for several days.”

The softly-spoken Madeira exudes gentle strength and quiet resilience. She is determined to see Timor-Leste’s art on the world stage. Her work employs traditional techniques and materials such as tais (woven Timorese textiles), betel nuts, earth and pigment to tell stories of Timorese women who suffered so much at the hands

of the Indonesian army.

The work for Venice is ambitious in scale – a 25-panel painting three metres in height – yet subtle in realisation. Pigment (including red earth from her home village) drips and pools, evoking blood or bodily fluids. Betel nut chewed and spat suggests gunshot wounds. Elsewhere, Madeira has applied paint over crochet segments to leave a stencilled pattern, a nod to her mother crocheting in the refugee camp. Parts of the tais are burned or scorched. The overall effect is equal parts beautiful gestural abstraction and crime scene, precisely what Madeira sought to emulate.

Overlaying this are “kiss” marks made by Madeira, who “performed” during the opening days, kissing the walls with lipstick and singing traditional village songs. It’s a startling detail. She explains that she returned to Timor in 1999 when the nation voted to become independent.

“I stayed with my brother, who was also an interpreter at the time with [the] UN. And he rented this nondescript house on [capital of Timor-Leste] Dili’s outskirts. He took me to the bedroom where I would stay, where I found lipstick in a linear, knee-high position on the wall all around,” says the artist.

“I asked the neighbour what it was, and he told me it used to be a torture room, that the women of Timor-Leste would be brought to this bedroom by the Indonesian military and were forced to put lipstick on and kiss the wall while they were raped. I felt like I needed to say something about this. Timor is a very patriarchal society; all the men speak about the great warriors of Timor-Leste buried at the Santa Cruz cemetery. The statues in Dili are all of the men who fought for independence. And I thought, ‘What about these women? Where are they buried? This is such an injustice’. The women fought so hard and used their bodies to fight for independence. Timor is a patriarchal society; they don’t talk much about women. When you talk about rape, that’s even worse. It’s all very shameful. It’s changing slightly because the younger women want to talk.”

Madeira and King note how moving it is to see the Timor-Leste flag flying over the Grand Canal, a small but mighty gesture about visibility. The artist cries as she relates how overwhelmed she was to have Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão officially open the pavilion in Venice. “For him to speak, to acknowledge the history, I thought ‘Now everyone’s going to listen because you’re a man’; it’s coming from a male perspective, and our people are finally going to pay attention.”

Australia is, of course, intimately connected to Timor-Leste via the Balibo Five, the five journalists – Australians Greg Shackleton and Tony Stewart, Britons Malcolm Rennie and Brian Peters, and New Zealander Gary Cunningham – murdered by Indonesian special forces while reporting on the impending 1975 invasion.

Madeira has a surprising connection to the tragedy. “My dad was the first to see them, witness ‘X’.” The family were refugees in a camp at Atambua when the head of the military came seeking a guide to return to Dili after reports of three Australian journalists being killed. Madeira’s father saw it as an opportunity to return and collect his daughter, who had been left behind.

“He said the one that took him, that showed him the bodies, said, ‘These are the Australian journalists who were killed because they had military uniforms on and they were fighting, and so we had to kill them’. And Dad told me himself, he looked at the bodies, he saw the uniforms, and he saw blood stains, but no bullet holes. And he thought to himself, ‘No, you guys killed them somewhere else’.” It’s a heart-stopping footnote to an already extraordinary tale that further underscores Madeira’s deep connection to her home country.

King describes Madeira as inherently an activist and also a teacher. “And when she found her way to art, she found the most powerful avenue to convey her message. I think Maria’s project is deeply feminist and feminine. Even though Kiss and Don’t Tell is harrowing, there’s been a lot of joy, deep commitment and harmony.”

Venice is a profound moment for both artist and her country. “When Indonesia invaded, most of us Timor-Leste people felt that we were going also to have a cultural genocide, that our culture would be finished,” Madeira says. “For me to have the chance to talk, be interviewed, do the performances, and paint … I feel like it’s my calling.”

Biennale di Venezia runs until November 24. Maria Madeira: Kiss and Don’t Tell is located at La Spazio Ravà San Polo 1011. labiennale.org

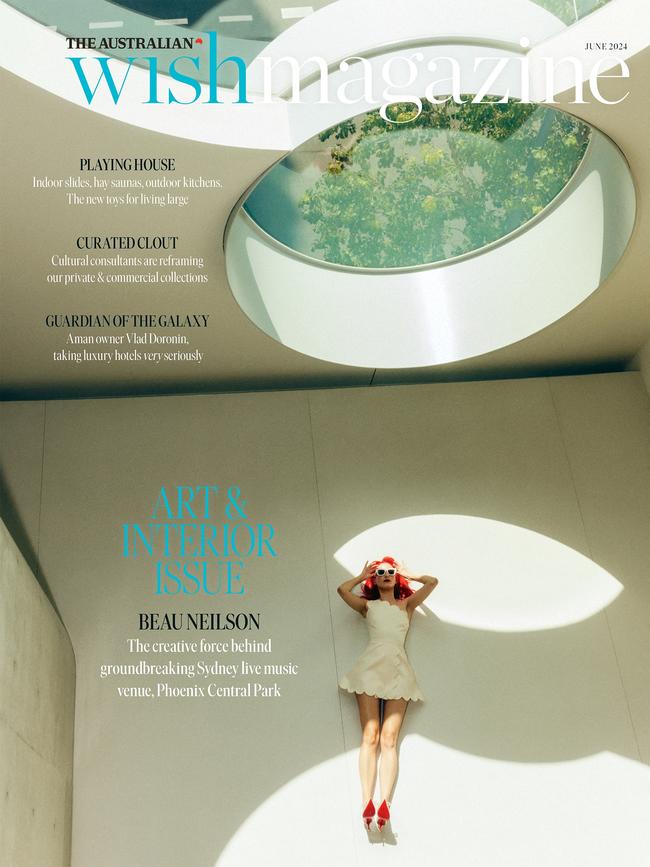

This story is from the June issue of WISH.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout