Curious case of The Waterhouse Natural Science Art Prize

The winning work at the Waterhouse Natural Science Art Prize features a torn-apart 100-year-old dictionary of Indigenous words. How this is supposed to represent ‘linguistic resilience’ is a mystery to me.

A little over six months ago, the South Australian Museum was showing the Australian Geographic Nature Photography Prize, reviewed in this column in September 2023. The most striking thing about that exhibition, as I observed at the time, was that it came from somewhere very different from the art world. The work was of high quality, there was a clear understanding of what was expected in each category, and the judging was competent. It was, in short, a very good exhibition of nature photography.

The current exhibition purports to be a natural history art prize, but the clear and specific criteria of natural history have been largely superseded by the confusion and disorientation that characterise the concept of “art” in contemporary cultural institutions. The foundation of scientific integrity has been lost in a multitude of extraneous concerns, whether for formal “innovation”, “creativity” or “diversity”, for quotas, tokenism and ideological signalling.

There is, for example, scarcely an example of formal natural history illustration, a genre with a long and distinguished tradition for many centuries. It may be unreasonable to expect a prize like this to restrict itself today to conventional botanical and zoological illustration, even in what is meant to be a scientific institution, and some of the most impressive natural history works here are in fact in non-traditional media. But it is equally anomalous for the genre to be so sparsely represented. Meanwhile the exhibition includes quite a few paintings and photographs that can hardly be considered to pertain to natural history even in the broadest interpretation, as well as too many works of very uneven quality.

Among these is the winner. It is a pair of grass trees made out of paper cut up into strips. The attached artist’s statement reads: “While simultaneously being dispossessed from land and waters, our words were stolen and commodified in the form of “Aboriginal Word” compendiums. This work transforms one of these fraudulent books into a pair of Xanthorrhoea … By transforming a flawed book into a plant that responds to wildfire by flowering abundantly, I draw parallels between my people’s linguistic resilience and our ecosystem’s enduring ability to rise from ashes.”

As a matter of fact, the book that was cut up to make this work was Aboriginal words and place names and their meanings, by Sydney J. Endacott, which originally appeared under a slightly different title in 1924 and was republished in an expanded version, with several reprints, after the war. Readers can easily find the 1963 edition published by Georgian House in Melbourne on Trove, or by searching for the title on Google.

Endacott’s book and others like it have been criticised, with some justification, for listing hundreds of Aboriginal words and names in alphabetical order without regard to the very different linguistic groups from which they originated. But Endacott does make it clear in his introduction he is aware of the existence of many different languages and dialects. He is also notably sympathetic to Indigenous peoples and condemns their mistreatment by modern Australians both at the beginning and the end of his short introduction to the book.

Perhaps the artist was too busy shredding the book to read it, but the problems with her work run much deeper. It might also have been worth thinking twice before using the emotive and facile word “stolen” in this case. From the earliest days of the First Fleet, there were men who took an interest in the Aborigines and their languages, who compiled lists of words and who tried to use them to communicate with the native peoples. Some of the original documents can be read online on the websites of our most important state and national libraries.

In subsequent decades and throughout the 19th century, many settlers, missionaries and anthropologists recorded or learnt Aboriginal languages.

Whatever their motives – whether practical, linguistic and anthropological or evangelical – these people who took time to learn Aboriginal languages are unlikely to have been the same ones who joined in massacres. Indeed the collection of linguistic information presupposes peaceful conditions and a degree of mutual trust and understanding.

This is one of the reasons that little is known about Tasmanian Indigenous languages, because hostilities broke out so early that there was little opportunity for peaceful interaction and communication, and by the time the fighting ended, the already small Aboriginal population had been almost entirely wiped out. No one has spoken any Tasmanian language for well over a century, and the current attempt to reconstruct what is known as Palawa Kani is a pastiche of vestiges from various originally unrelated languages.

The only reason that these vestiges exist at all is because they were recorded by curious or sympathetic settlers. And the same is true all over Australia: of about 250 languages and dialects once spoken in this continent, more than half are extinct; according to a recent ABC article, just 123 still survive, and only a dozen are still vital. A list of Aboriginal languages on Wikipedia gives an estimate for the number of people who still speak the remaining languages, often just a handful of elderly men and women.

If we know anything about the extinct languages, and if there is any hope that the moribund ones can be relearned, is because of the interest of people who took the trouble to record them generations ago. So perhaps “stolen” is a poor choice of word. But the whole label reads like a set of sentimental and ideological buttons, pushed one after the other.

There are fortunately some works that do illustrate both traditional and unexpected approaches to picturing the world of natural history, including Pauline Denwar’s watercolour Insecta, a collection of Australian insects that also unobtrusively makes a scientific and ecological point because those that are flourishing are in full colour while the endangered or extinct ones are pale or colourless.

The finest natural history drawing is by Jane Hylton, represented by two works. One is a large sheet covered in the meandering tendrils of a shrub known as Kennedia prostrata (apparently colloquially called Running postman); some of the tendrils, leaves and red flowers are painted in colour, while others are left in ink outline, conveying the way, as the artist explains, much of the shrub is hidden in the tangle of other plants in the garden. But especially effective and poetic is another work by Hylton in which the vine Muehlenbeckia is painted in oil on a battered sheet of galvanised iron. This is one of the pieces – at once refined and original – that would have been a far more worthy winner of this year’s prize, if it had been judged on appropriate aesthetic criteria.

Cathy Gray’s Ningaloo assembles 557 fish species in a kind of vortex, representing the surviving biodiversity of the Ningaloo Marine Park in Western Australia. Susannah Blaxill’s Hakea seed pods, a large charcoal drawing, is another of the finest examples of botanical draughtsmanship in this exhibition.

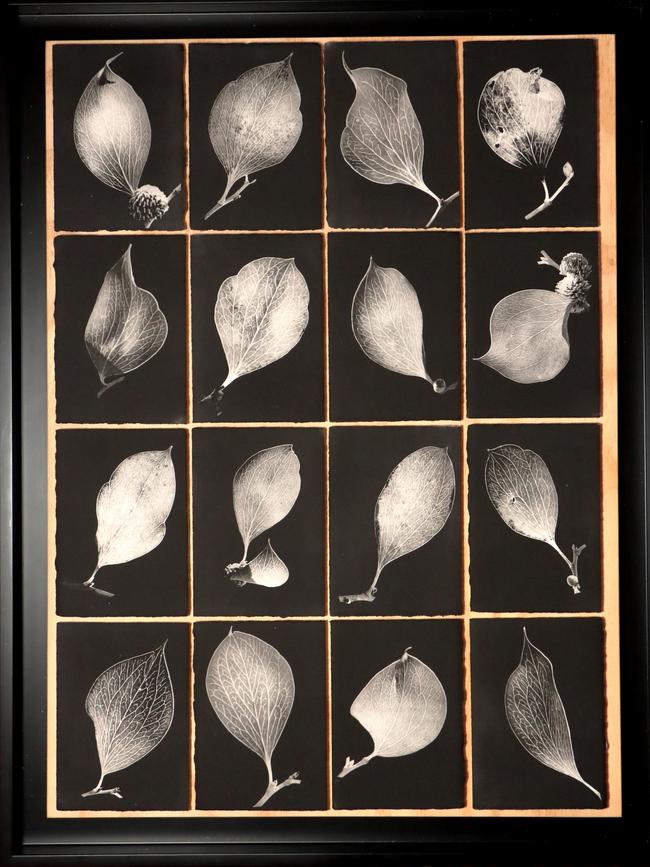

Hakea leaves are the subject of another fine work, a series of photogravures, a medium where a photographic image is transferred onto an etching plate and printed; here it seems that the negative has been used, giving the leaves a ghostlike appearance and bringing out their network of veins.

In sculpture, two works deal with inanimate natural processes: one is Beric Henderson’s Anatomy of a wave, built up by ink drawing on 40 layers of transparent Perspex, and the other is Charmian Hearder’s Eolian Saltation, a group of hand built clay models of dunes, representing the ripple patterns formed by wind on the sand of desert dunes, just as by the movement of the sea on sand underwater. Eolian or Aeolian refers to the action of the wind – named for the ancient wind god Aeolus – and is a form of erosion, only here shaping and reshaping a landscape composed of loose particles.

Robyn Booth has a series of clay tablets moulded by direct impression into the channels made in eucalyptus trunks by the larvae of the longhorn beetle.

Jessica Murtagh’s Six is the loneliest number is a delicate work in blown glass; its accompanying label explains the enigmatic title as referring to the six specimens that alone survive of the Mongarlowe Mallee tree – although how the form of the work relates to its ostensible subject remains unexplained.

Among the most memorable pieces in the exhibition, and another that should have been a contender for the first prize, is Sophia Dacy-Cole’s Soil breathes. This is a short video work in which a small sample of damp soil, rich in humus, has been filmed, or photographed, through a microscope.

At this level of magnification, and with the acceleration of time lapse, the soil appears to be alive and in constant movement, as though actually breathing, as the title suggests; we discover it in fact to be full of minute creatures that live in and on the decomposing plant matter, and at the same time of new and emerging organic life, roots and germinating seeds. Far from being inert, this small clod of earth appears to be in constant, restless motion. A dimension of life first revealed to us by the invention of the microscope four centuries ago can still fill us with a sense of wonder.

A work like this, although in an entirely unconventional medium, remains in sympathy with the spirit of natural history: approaching the natural world with curiosity and the scientific will to understand the phenomena of life, but also the humility to appreciate the true scale of human experience and endeavour in the vast extent and unimaginable temporal reach of the natural environment.

The Waterhouse Natural Science Art Prize

South Australian Museum to June 10

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout