Rey Flemings helps billionaires spend their money

If you yearn to watch Beyoncé from the wings or walk the red carpet at the Met Gala, Rey Flemings can make it happen – for a price.

Congratulations, you’re rich! Not just rich, but something beyond that. The sums of money to which you have access are surreal – abstract chains of numbers and commas that whir and multiply as you sleep. Perhaps you have sold your business for a couple of billion. Maybe you’re a Silicon Valley chief executive. You could be a star of some description – sport, film, music. It doesn’t matter. What matters is the money. Yours is a world of fairytale abundance yet with none of the fairytale consequences. At the stroke of midnight, your clothes remain fabulous and your sportscar does not turn into a pumpkin. You can have whatever you want, and you regularly do.

Only, after a while, you start to look around. You have a lot, yes, but you have come to realise you cannot really, truly have whatever you want. No matter how much money you possess, there are certain things you desire that remain tantalisingly out of reach. Parties you would like to go to. People you would like to meet. Problems that can’t be solved simply by turning on a money hose. So, what do you do when this uncomfortable feeling begins to gnaw at you? Who do you turn to for help?

The answer, for a growing number of the world’s super-rich, is Rey Flemings. The 50-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, is the founder of Myria, a company that operates out of a light, airy office in Beverly Hills. Myria advertises itself as a “concierge” service for “the most successful people in the world” – which is a somewhat coy way of saying that Flemings is an Olympic-level fixer, somebody who can make the wildest, most feverish dreams of the insanely wealthy come true.

Want to impress the guests at your Miami house-warming? Flemings can arrange to borrow some priceless artworks from the Smithsonian Institution for the occasion. Want your private security team to be allowed to carry firearms while visiting a European country that expressly forbids private security teams carrying firearms? Flemings can convince its government that you, a private US citizen, should receive the same level of protection as a diplomat. Want to go to some of the most exclusive events on the planet – the Academy Awards, the Met Gala? Flemings can get you through the door.

Flemings is a soothing, steady presence: attentive, understanding, but armed with a gentle authority. It’s not hard to see how he has made a career out of dealing with people whose expectations may be a little high. He has the skill-set of a world-class maître d’.

He is also one of the planet’s leading authorities on both the anthropology and psychology of the very, very rich. Over our two hours together, he uses various technical terms when discussing them. So, for example, Flemings only works with “ultra-high-net-worth individuals” (UHNWI) – somebody worth, at an absolute minimum, $US30 million. Often these people will have come into their fortune via something known as a “wealth event”, which is “something that occurs and gives a person a life-changing amount of money”, he explains cheerfully. “That could be the sale of a business, an inheritance, a lottery win, or because of a court judgment or settlement.” He talks about the concept of “post-luxury”: the idea that, once you hit a certain level of extreme wealth, you transcend the desire for the old trappings of success. Why buy a Ferrari when your net worth would allow you to buy the entire Ferrari corporation? “I know a bunch of guys in that position who don’t own a single luxury car,” Flemings says. “Some people become almost allergic to it.” He then talks about “post-post-luxury”, which is more about experiences than possessions. “It’s not a ‘stuff’ thing. It’s about, ‘Who do I get to do it with? Do I get to feel special in that moment?’”

He rolls out a bit more jargon. There is a distinction, he says, between clients who made their own money and those born into great wealth. “So the phrase in the industry is ‘first generation’ versus ‘heirs’,” he says. “Generally speaking, first-generation clients are easier to work with, because when you work for a living and you’re out there dealing with stuff, it creates a natural empathy. And listen, there are many wonderful heirs, but they can be more difficult, nitpicky clients. Because in their world they’ve not been exposed to the reality of managing people and everything that goes with that.”

The problem with “first gens”, though, is that despite the great fortunes they have amassed, they can sometimes tie themselves in knots when it comes to spending it. Flemings, who is rigorous about maintaining client confidentiality, gives an example of a first-gen UHNWI who wanted him to arrange an elaborate 50th birthday party, complete with a list of very specific requirements. Flemings explained that he could indeed arrange this “amazing, crazy experience” for him and his family, and that it would cost $1 million. At which point the client “freaked out”, because they can “remember very vividly when they made less per year than they’re now about to spend on renting a house for a week”. So they pick a lower number – $700,000 – and insist that’s the most they will spend. Flemings sighs and gives a patient smile. “Sir,” he says, addressing me as though I am the client, “you are worth $3.1 billion. The difference between a $700,000 event and a $1 million event is completely irrelevant. But the $700,000 event is not going to give you the experience you asked for. You’re just getting in your own way.”

But the key to Flemings’ success – and Myria’s modus operandi – is the fact that many things cannot be acquired or accessed using money alone: there are innumerable invisible velvet ropes criss-crossing reality that your bank balance cannot help you cross. “Go to any event – a sports stadium, a fashion show – and there are things going on around you that you just don’t see. Like, there are worlds within worlds within worlds,” he says. If you’re an A-list star then you probably have access to these worlds. But even if you have “orders of magnitude more money” than the hot young actor who has just quietly been ushered backstage, it doesn’t really matter. You’re not invited.

Flemings has condensed this conundrum into a simple axiom: “Cool people want to be rich. Rich people want to be cool. Everybody wants to feel special.”

And, of course, the cooler something is, the harder it is to obtain. Flemings leans forward slightly and gives me what feels like a well-honed pitch. When it comes to lifestyle and leisure, which are the areas he tends to focus on, everything you may desire can be graded from one to five, depending on how hard it is to acquire.

Level one things are items or experiences that are openly advertised and simple to purchase, such as tickets to Coachella. Level two is similar, just a little more expensive. “Say you want VIP passes to Coachella,” he says. “Well, you can buy them online for a thousand bucks. Your assistant can do it. Your kids can do it. It’s totally easy.”

But say you yearn to go to an exclusive Coachella after-party. “The biggest is in the largest, fanciest villa in the area, Zenyara,” Flemings says. “The swimming pool is like a freaking lake. There are jet skis. It’s gorgeous, and all the celebrity after-parties are there.” The problem is that you cannot simply go online and buy a ticket. “You have entered the world of ‘off-market’,” Flemings says, which means we are now at level three. Here, the things you want are available if you have the money, but there is no public marketplace. “It’s opaque and complicated.” So you would probably use a third party, a nightclub promoter or a concierge service such as Quintessentially, which might arrange for you to buy a Coachella artist’s pass granting you access to all the celebrities and jet skis and pools the size of inland seas. “And the market rate is about seven grand.”

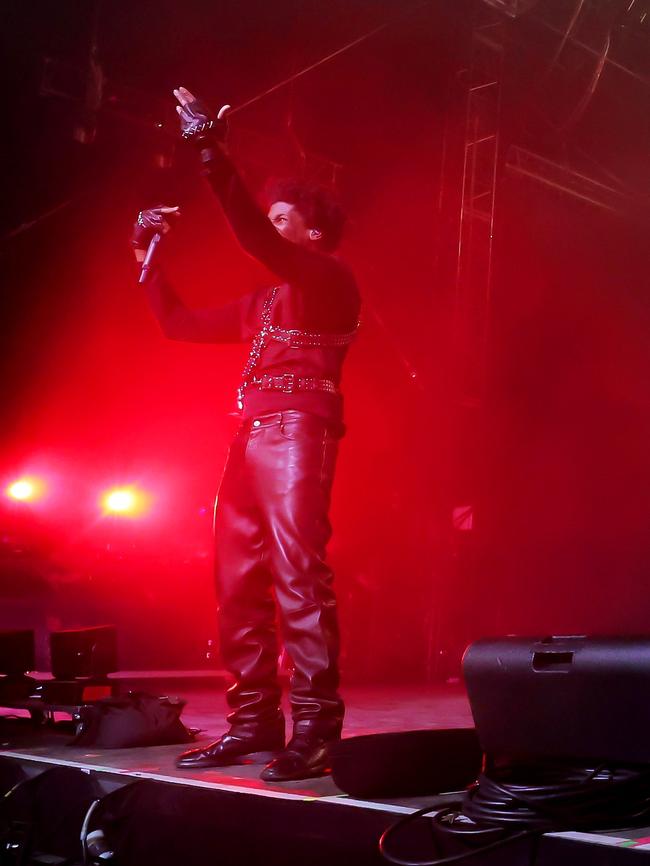

So now you’re at Coachella with your artist’s pass. Beyoncé is performing and you want to stand on the wings of the stage while she sings. You wave your $7000 artist’s pass at the stage-side security team, but they shake their heads. “That does not get you onto Beyoncé’s stage. That’s a level four. Parkwood Entertainment is her management company, and you’ve got to know someone there and they have to want you there explicitly,” Flemings says, stressing every syllable. “Another four would be walking the red carpet at the Met Gala. These sorts of things are very, very hard.”

It’s no longer a question of just finding the right person and giving them lots of money, but of persuading the gatekeepers that you belong there. “It’s like, who are you? There are 500 tickets to the Met Gala. Most of them go to the most famous people in the world. So why you? What’s your reputation? What are your relationships? It’s not about the money anymore. In fact, money is the last of the questions.”

Finally, he says, there are the level fives, the practically impossible ones. Hanging out with Beyoncé after she comes off stage would be a five. “Beyoncé herself has to want you on her tour bus.”

Most outfits that sell themselves as “luxury concierge” services only really deal in level twos and threes, Flemings says. He is about fours and, very occasionally, fives: the jobs that are fundamentally about knowing the right people and approaching them in the right way. “We’ve been building this crazy card index and network for a very long time.”

But how does Flemings find himself inhabiting this heightened world of money and desire and near-impossible demands? Because it was not the world he was born into.

“I grew up as poor as poor can get in the United States,” he says. His mother was an elementary school teacher in Memphis and a single parent. “I did not know my father.” Perhaps as a result, he thinks there was something about him that made people want to take him under their wings. One day the head teacher of his tough inner-city junior high school told him he had been put forward to take an entrance exam to Memphis University School, one of the most exclusive private schools in America’s southeast. He passed, won a scholarship, and suddenly found himself surrounded by wealth and privilege. “The kids who went to that school were, you know, the son of the chief executive of Federal Express. The son of the largest cotton merchant in the world. I’m there riding the bus in from the ghetto and these kids are driving up in Range Rovers they were given for their 16th birthdays.”

By his early twenties he was working for a financial services firm. And as a result of being the only person who understood how to put together and operate newfangled PowerPoint presentations, he found himself standing in front of some of the wealthiest people in the region and talking to them about “esoteric financial concepts”, despite being a “wet-behind-the-ears kid”. Over time, though, he began to develop a feel for the millionaires and billionaires sitting before him. Comprehending what somebody wants to do with their money is as clear a window to the soul as any. “It was about understanding their needs and fears and hopes and dreams.”

He began to develop a web of well-placed connections. Over the next two decades, Flemings bounced between tech and entertainment, helping found and develop start-ups, running a music foundation in Memphis, working with Justin Timberlake and becoming part of his “family office” – a wealth-management firm focused solely on a particular UHNWI and their loved ones – before bouncing back to the tech space as chief executive for a start-up called Particle, which was eventually acquired by Apple. Conversant in the worlds of both celebrity and Silicon Valley, and by now well attuned to the psyche of the super-rich, Flemings found he had developed a reputation as somebody who Knew People and could Make Things Happen. As a favour, he’d arranged a lavish European holiday for a tech founder who’d experienced a wealth event after selling up to Amazon, and very quickly word got around that Flemings was the guy you needed to speak to if you wanted something special.

In 2016 he launched his first luxury concierge service, The Blue, in which he served as point man for a select group of 80 clients worth a combined $US400 billion. But the demands on his time and person were too great to be tenable. “No one is immune to stress,” he says. “And when you’re running troops on the ground, it is stressful.” So last year he launched Myria, a digital concierge system that allows members to be plugged into a network of luxury service providers. It is, in effect, an online marketplace for things that are “off-market” – the level threes, fours and fives. For $US25,000 you can download the Myria app, which presents you with a simple prompt: “I want to … ” Clients then type in what they want, and this request is circulated around the network of providers. It’s like Uber, only for ridiculous things rather than taxis. You’re charged a fee every time you use it – the more difficult the request, the higher the fee.

Often, though, it’s less coldly transactional than that. If a government contact helps to expedite a visa for one of Flemings’ clients, say, or if someone can make courtside basketball seats happen, they’re not necessarily doing it in the expectation of cash payment. “When people in our business do a favour, that favour is added to the favour bank. Some people want money, and we pay those people. But for other people it’s not about the money. They want other things,” he says. “And one of the interesting parts of our business is balancing all that and paying down our debts to our network.”

Providers can pitch their services to Myria. I ask Flemings what he thinks the Titan submarine disaster – in which five people died after their private submersible seemingly imploded during a trip to view the wreck of the Titanic – reveals about the world of UHNWIs. He says Myria was in fact approached by the company running the trips to see if any of their clients would be interested. “When we saw the offer, we never showed that to a single person,” he says. “The word on the street was that this is not the outfit you want to be using. And so we never sold it.”

Clients can request anything, provided it’s neither “gross” nor illegal. “We’re not in the business of helping anyone be shady people,” Flemings says. “You can’t be an asshole.”

Indeed, if a potential client vibes as pushy, entitled, shallow or egomaniacal, they will not be granted membership. This is as much a practical as a moral concern. If you’re going to be plugged into a world of off-market favours and unparalleled access, then you have to be able to carry yourself in the right way. The whole thing falls apart if you manage to snag that stage-side pass to the Beyoncé gig only to then rush on stage and attempt to join in the Single Ladies dance routine.

To become a Myria member you must complete a sizeable set of questionnaires about who you are, what you want, what makes you happy, and other topics usually reserved for the psychiatrist’s couch. “Most people who apply can’t get in,” Flemings says. “We’re trying to build a community of the 10,000 most successful, socially responsible, cool, interesting and nicest people on the planet. That’s our goal.”

This is a great marketing hook: what Silicon Valley founder or A-list actor wouldn’t want membership to something that grants them access to cool stuff while also affirming their all-round goodness? But Flemings seems genuinely sympathetic to, and even a little protective of, the super-rich. He trades in making them happy and yet, very often, being both super-rich and super-happy is hard. When you’re that wealthy, you can end up isolated and mistrustful of others. It’s revealing that one service many clients really want is just to meet other people. There is a huge demand for summer camps, where very rich people and their children can hang out with other families like them. Sometimes he arranges for members to go on holiday with celebrities. “We’ve brokered vacations between our clients and Oscar-winning actors or Grammy-winning recording artists. Because they’re of a similar age, similar mind, and we know both parties,” he says. “Like, you guys are going to freaking love each other.”

Often, the super-rich find themselves caught in a dynamic in which they believe the only route to fulfilment is the acquiring of more money for its own sake. “Some people just want more and more and more and more. I would suggest that’s probably a sub-optimal way to lead your life,” he says with a courtier’s tact. “And an unhappy one.”

Ultimately, he continues, so much of what he tries to impart to his clients is that happiness is not a commodity or something you can simply ask your PA to schedule. “It’s not something you ‘do’. It’s something you have to ‘be’. And learning how to be happy, and how not to condition that happiness on chasing the next thing, is really important.” He admits that, over the course of his working life, he has had to get his head around this as much as anyone.

Flemings is not yet a UHNWI himself but, in time, he may become one. “If I had all the money in the world, the very first thing I would do is take my phone and throw it in the ocean. Set it on fire. Throw it off a building. I have used this thing enough to last a lifetime,” he says.

For the time being, he is still busy helping some of the world’s richest people get what they want. “Yeah, they might go and spend $1 million a week on vacation. But they’re worth billions and billions of dollars. I don’t think that’s selfish, I think it’s a great thing,” he says. “Our clients have won the game of life. Why not enjoy it?”

This article appears in the November issue of WISH Magazine, out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout