If these walls could talk: political ghosts of Old Parliament House

Bob Hawke couldn’t get out of there quickly enough, while Paul Keating said something was lost when politicians moved out of Canberra’s Old Parliament House. What will never be forgotten are these stories.

When Parliament House in Canberra was opened by the Duke of York (later King George VI) on May 9, 1927, the gleaming white exterior resembling a wedding cake stood out for miles and miles amid the sheep paddocks of the new bush capital. Designed by chief architect John Smith Murdoch, this was a new building for a new capital city for a still relatively new federated nation. Parliament had first met at Melbourne’s Royal Exhibition Building and then relocated to the Victorian Parliament. Now, federal politicians had a parliament of their own.

It was, however, only meant to be temporary. A permanent parliament house would one day be built for the capital. The debate about what it would look like and where it would be located began straight away. At Yarralumla? Perhaps on the shore of the still to be constructed Lake Burley Griffin? Or on Capital Hill?

In the meantime, the provisional Parliament House was renovated and expanded several times before the Fraser government decided to build a new one a few hundred metres away. By the 1970s it was bursting at the seams due to the expanding number of politicians and the arrival of ministerial staff, and an office annex was built. By the 1980s, the building was literally crumbling.

Bob Hawke, the last prime minister to serve in what became “Old” Parliament House, could not wait to vacate the cramped building and move to more modern facilities in “New” Parliament House in 1988. He had laid the foundation stone for the new building in 1983.

“There was just so much bullshit talked about how terrible it was that we were moving from the old place,” Hawke told me. “The working conditions in that old Parliament House would not have passed the conditions of the Factories and Shops Act in any state. The working conditions were appalling. As far as I was concerned it could not happen quickly enough.”

Hawke had only been in the building since 1980. Paul Keating, the last treasurer in the old building, had been there since 1969. He was a member of the parliamentary committee that oversaw the design and construction of the new parliament house. But he thought something was lost when they moved out. “The ambience changed – for the worse,” Keating reflected. “Although one has to have a modern functional building with space, the closeness, the clubbiness, evaporated when we moved to Capital Hill.”

John Howard, who arrived in 1974, was the last opposition leader to serve in Old Parliament House. He agreed with Keating. “The intimacy and the camaraderie were better,” Howard recalled. “When it was debated inside the government, I was in favour of keeping the old Parliament House and extending it. But the monumentalists won the day.”

Malcolm Fraser came to regret the new Parliament House, which had cost an eye-watering $1.1 billion by the time it was opened by George VI’s daughter, Queen Elizabeth II, on May 9, 1988. Fraser saw it as too grand and extravagant, and lamented that it changed the character of our politics.

Old Parliament House, now housing the Museum of Australian Democracy, breathes history from the moment you see it. The building was closed from March to June last year due to the Covid-19 pandemic (and at press time is closed again), enabling the museum to bring forward several projects in the culmination of its three-year capital works program, which includes upgrades to building systems and conservation work.

WISH was given exclusive and open access to the museum to photograph it.

Old Parliament House sits below its ostentatious successor within a triangle of roads, bordered by King George and Queen Victoria terraces and boxed by Parliamentary Square. Gardens with tennis courts sit on either side. The front lawn, home to the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, slopes towards the lake.

A colonnade of flags marks out a car park directly in front. The grey steps leading up to the wood and glass doors beneath a small portico evoke memories of Gough Whitlam’s defiant speech on Remembrance Day 1975 after his dismissal by Governor-General Sir John Kerr. On that day of drama, politicians addressed the heaving crowds in front of the building. The Governor-General’s official secretary, David Smith, read out a proclamation dissolving Parliament from the steps. Then, carving his way through the crowd, the towering Whitlam appeared. “Well may we say… ” You know the rest.

There was violence and vandalism around Australia that day, and fears of a riot at Parliament House. Country Party leader Doug Anthony told me that security personnel ushered him back inside his office, the first on the left on the main floor, and locked the door, fearing protesters might break-in.

Inside, after ascending the polished wooden stairs, you arrive at King’s Hall, the beating heart of the building. Pendant lights hang from the moulded ceiling, while skylights allow natural light to pour in. Bronze bas-relief plaques of political pioneers are fixed to white columns around the room. Official portraits of prime ministers, parliamentary officers and governors-general once adorned the walls.

In its day, the building was a hive of activity. Around the pedestalled statue of King George V, politicians would brush shoulders with each other, and with public servants, staff, journalists, lobbyists and citizens. Politicians would zig-zag across the parqueted floor of King’s Hall on their way to other offices, the cabinet and party rooms, and the parliamentary chambers and library. It provided an unrivalled vantage point. Legendary journalist Alan Reid would lean his elbow on a glass cabinet encasing a 1297 edition of Magna Carta to watch the passing parliamentary menagerie. He would often stop politicians, or they would approach him, to trade information.

When Prime Minister John Curtin died in 1945, he lay in state in King’s Hall before his coffin was flown to Perth for a state funeral. When former prime minister Ben Chifley died in 1951, he too lay in state in King’s Hall before being flown to Bathurst for his funeral.

Chifley’s death was announced during the Jubilee Ball, held in King’s Hall. He had not attended, preferring to read a western and have his usual dinner of tea and toast at the Hotel Kurrajong. When Prime Minister Robert Menzies learnt that Chifley had had a heart attack, he interrupted the band and told everyone to go home as a mark of respect to “a great Australian”.

Behind the statue of George V is the parliamentary library, and beyond that the dining room and non-members’ bar. The refreshment rooms once included a billiards room and lounge that was later converted to an additional dining area. These rooms and furnishings showcase the so-called Inter War Stripped Classical style, which incorporates Greek patterns and decorative elements.

Menzies held his farewell press conference from the dining room in 1966. As this was to be broadcast live on national television and he would arrive as the cameras rolled, he instructed press secretary Tony Eggleton to allow time for him to stop off for “a nervous pee” after walking around from his office.

The library, dining room and bar were places for spontaneous interactions and socialising that helped forge friendships across the political divide. Journalists could soak up news tips while downing the amber ale and then scramble upstairs to the press gallery to file stories late into the night.

The House of Representatives and Senate chambers are entered directly off King’s Hall – green carpet for the House and red carpet for the Senate. As you step in, your eyes are drawn to the lower-level green and red soft leather benches, the centre table, and the chair occupied by the Speaker or President.

The galleries above are for citizens, special visitors and media. The chambers are cavernous yet intimate. Shafts of light stream through the upper windows of the Senate while the high House windows remain covered for now, a reminder of MPs who did not want the light beaming in while they debated the important business of the day.

These chambers have witnessed some of the most momentous events in the nation’s history, such as announcements of the sending of troops to war, the deaths of kings and queens, and celebrations of the nation’s sporting, scientific and cultural triumphs. But most Australians only heard parliament on radio rather than saw it as the first television broadcast did not occur until the joint sitting of parliament in 1974.

In 1955, the House of Representatives’ Privileges Committee found that journalist Frank Browne had impugned the integrity of Labor MP Charles Morgan when implying he was involved in an “immigration racket”. Browne and Ray Fitzpatrick, his publisher, gave evidence to the committee and were later put on trial.

Browne and Fitzpatrick were summoned before the Bar of the House – a wooden rod placed across the entrance to the chamber. Menzies successfully moved a motion that they be jailed for breaching parliamentary privilege and both spent three months in Goulburn jail – a reminder of the power of the parliament.

Keating, the youngest MP, would meet with Arthur Calwell, the eldest MP, during the adjournment debate in the House of Representatives. When it concluded, they would put on their coats and head to the Hotel Kurrajong where they lodged, a 10-to-15-minute walk. Liberal senator Chris Puplick told me that he liked to sneak into the Senate chamber and sink into a red leather bench to read a good book.

At the top of the steps in King’s Hall are the main toilets, where members of the public could bump into politicians. When Enid Lyons and Dorothy Tangney became the first women elected to parliament in 1943, there were no ladies’ toilets and the first female amenity was not installed until 1974.

In 1970, Keating found himself standing at the urinal next to Jim Cairns, leader of the Vietnam moratorium movement. “Paul, I’m very disappointed you’re not wearing your moratorium badge,” Cairns said. “Look, Jim,” Keating replied. “That’s the difference between you and me. I’m not here to protest; I’m here to be in charge.”

When Hawke convened his national economic summit in April 1983, he wanted to use the House chamber to host politicians, bureaucrats, business, union and community leaders. The idea shocked the public service; the chamber was sacrosanct. But Hawke insisted and the summit went ahead.

Ross Garnaut, economic adviser to Hawke, recalled having a pee in the public toilet next to Hawke’s principal private secretary, Graham Evans, during the summit. Treasury Secretary John Stone walked in. “You two blokes should be ashamed,” Stone said. “This is not how policy should be made.”

The corridors off King’s Hall are where the legislative and executive branches blend. This is unlike most other parliamentary buildings, where the prime minister and ministers, or president and cabinet secretaries, are located separately when not sitting. The media being in the same building adds to the hothouse environment.

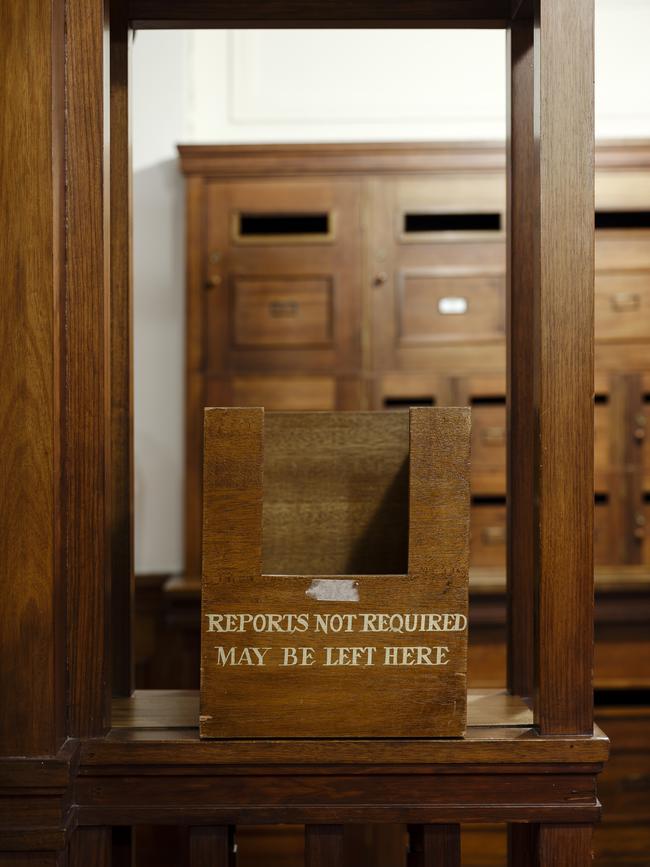

The government party room has lounges, desks, bookcases, pigeonholes, lockers and phone boxes. The design of the furniture is simple and functional, and classical in style. It was envisaged that this was where politicians would work when they were not in the chambers, and accordingly, the parliamentary offices are notoriously small and were often shared by two MPs. They are not much bigger than a broom cupboard.

The party rooms have also witnessed momentous events in Australian political history. In 1971, John Gorton watched as votes on a motion of confidence in his leadership piled up in equal measure and were tied. He exercised a casting vote – to which some doubt that he was entitled – against himself and resigned the prime ministership.

The opposition party room was bitterly divided in the fifties. In 1954, opposition leader H.V. “Doc” Evatt defeated a leadership spill motion at a fiery caucus meeting. Red-faced and with pen and paper in hand, he leapt onto a table and demanded the disloyal MPs be recorded. “Get their names!” he shouted. “Get their names.”

At the end of the front corridor that runs alongside the House of Representatives is the Prime Minister’s Suite. Added during extensions to the building in 1972-73, it was occupied by Whitlam, Fraser and Hawke. The Prime Minister’s Office has room for a desk and chairs, bookshelf, a lounge and coffee table, and includes a toilet and shower annex.

Whitlam, who liked to recline on the lounge to read papers, had his desk at the far end facing the entry door. Fraser moved the prime ministerial desk to the opposite end, and a peep hole through a bookcase allowed his principal private secretary to look over his shoulder from the adjoining office to see if he was busy.

Hawke positioned his desk with his back to the front windows. He liked to watch horse races or cricket, and the news, on a television atop a credenza. Hawke could call ministers directly from a phone on his desk. He often buzzed Keating, whose office was just below and who came up for a chat and a cigar via a fire escape stairwell.

Graham Freudenberg, who worked as a speechwriter for Whitlam and Hawke, recalled there was not much difference in the way the two Labor prime ministers worked. “Access was very easy,” he recalled, “and they both stocked the fridge very well.”

The smaller suite that Menzies occupied for 16 years straight had dark wood-panelled walls with framed photos of the Queen and Prince Philip, cricketers Don Bradman and Keith Miller, and one of him and Winston Churchill. Menzies also displayed a painting by Churchill, Cap D’Antibes, given to him in 1955.

In the evenings, Menzies would gravitate to what was known as the prime minister’s anteroom – now the cabinet anteroom – where he would mix drinks for staff, ministers and public servants, and hold court with anecdotes and stories. His usual pre-dinner drink was a martini mixed in a jug with ice and lemon rind. (This room also had a bed that folded into the wall for prime ministerial napping.)

Menzies sat at the same pedestal desk as his predecessors, designed especially for the suite. Curtin and Menzies often shared a cup of tea in the office and chatted about all manner of things, often not politics. So did Menzies and Chifley during their respective periods as prime minister and opposition leader.

There are few areas for prime ministers to entertain guests or host private dinners with colleagues. The exception was the President of the Senate’s Suite, which had a large dining table. (The Speaker’s Suite was remodelled in 1977 and a dining room was added.)

Former President Doug McClelland recalled being asked by deputy prime minister Lionel Bowen to use his dining facilities, which included a small kitchen, to help heal occasional rifts between Hawke and Keating. “We’d break bread and try and patch it up,” he recalled. “It would help smooth over any temporary fractures in the relationship.”

Doug Anthony, whose father was a minister in the Menzies government, recalled as a boy wandering into Menzies’ office simply to say hello. He would also venture to the lower floor and basement, roller-skate to the kitchen to ask the cooks for a piece of chocolate cake and talk to the men shovelling coal into the boilers.

These lower floors, not all accessible to the public, include a large kitchen, butcher’s room, pastry room, cool rooms and vegetable store, with industrial mixers, ovens and refrigerators. They underscore the notion of the building as a mini-city, which also included a sauna room and barber shop.

The press gallery is a rabbit warren of offices and broadcasting studios located on the upper floor on the House of Representatives side of the building. Here, journalists working for newspapers, magazines, wire services, television and radio competed for scoops side by side. By 1988, there were around 300 journalists working in the building.

The centre of power is the cabinet room. The large square table with a hole in the centre was designed to accommodate the Whitlam cabinet, which included all ministers. Public servants sat at smaller tables in the corners of the room. Light streamed in from one side of the room through sheer curtains. A thick layer of cigar and cigarette smoke always hung in the air during meetings.

The cabinet anteroom was where junior ministers or public servants would wait before being invited inside. The kitchenette would be used to prepare sandwiches, pies and sausage rolls, and often lamingtons and scones. Ministers could press a button to summon an attendant to arrange food or drinks, or to convey messages.

When the House adjourned for the last time at 1.33 am on May 27, 1988, politicians and parliamentary staff, as well as journalists in the gallery, looped arms and sang Auld Lang Syne. The parties had gone on for weeks. When the Senate adjourned at 12.26 am on June 3, 1988, streamers and papers were thrown, and beer cans were brought in. It was the end of an era.

The character of Australian politics changed. So did the geography of power. The vast new building created distance between politicians and between them and their citizens. Thankfully, the old building has been magnificently preserved and the old ways can still be glimpsed. It serves as a time tunnel to the past and a reminder of what once was.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout