Australia’s most outrageous dandy Leigh Bowery is honoured with an NGV ball

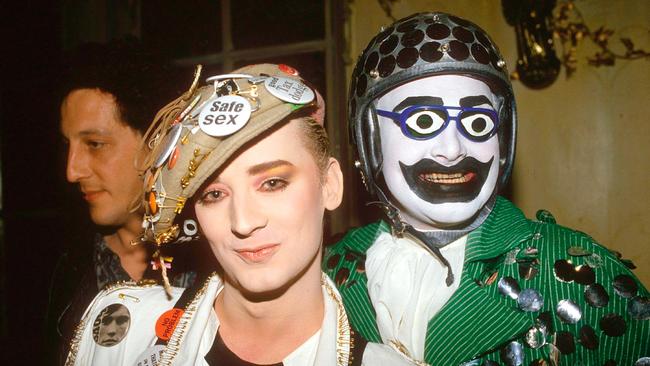

This month the legacy of Australia’s serial provocateur – whose bold creative output captured the imagination of everyone from Boy George to Lucian Freud – is saluted with the inaugural Bowery Ball, a queer celebration of drag, burlesque and performance.

For about six months after he moved from Melbourne to London in October 1980, Leigh Bowery wrote a diary. The 19-year-old had escaped the Melbourne suburbs for the cultural riches and heady night life of the British capital. He was staying at a youth hostel, and kept a record of his hopes, dreams, discoveries and disappointments.

On Sunday, January 25, 1981, he noted with a lack of enthusiasm that the next day he would be starting work at Burger King, Piccadilly Circus. Flipping burgers wasn’t exactly what he had in mind for his brilliant career but he needed the money. “Why did I come to England?” he asks himself. “Answer: to get the best clothes ideas and mix with celebrities and eventually become famous. Pretty tall order.”

And yet, within a decade, Bowery had indeed become famous. He was an outrageous dandy in the manner of Oscar Wilde, Quentin Crisp and Lindsay Kemp – but with his own unique style – and made his life into a work of art. Bowery’s milieu was the Soho underground of queer nightclubs and studios; his occupation that of performance artist, club host, costume designer, artist’s model and serial provocateur.

His is not a household name and he would not be confused with better-known Aussie expats of the 1980s such as Men at Work, INXS and Paul Hogan, but his influence and legacy run across fashion, art, film and music. Singer Boy George, artist Lucian Freud, choreographer Michael Clark, and designers John Galliano and Alexander McQueen were all drawn to his larger-than-life presence and sensibility.

Melbourne-based artist Garrett Huxley followed in Bowery’s footsteps when, straight after finishing high school in the late 1980s, he fled the Gold Coast and boarded a plane to London. He’d grown up reading issues of British style magazines The Face and i-D, and wanted to be part of the club scene there. At Kinky Gerlinky club night in 1993 he saw Bowery and Nicola Bateman perform their notorious act called The Birth, inspired by “pope of trash” director John Waters and his movie Female Trouble, which featured actor and drag artist Divine. It had Bateman harnessed upside down to Bowery, who then proceeded to give “birth” to her with quantities of fake blood and strings of sausages.

“I just remember the whole club roaring – no one could believe the audacity and the shock of it,” Huxley recalls. “Kinky Gerlinky was a very special place. It was just very free – you could wear what you wanted, do what you wanted, any sexuality. And Leigh Bowery was like the centre of that freedom.”

Huxley and his husband Will Huxley are The Huxleys, a queer art duo who cite Bowery as an influence on their own work. Will Huxley says Bowery was an artist who absorbed the culture around him – from Bauhaus designer Oskar Schlemmer to photographer Horst P. Horst and artist Salvador Dali, and much else besides – and transformed it all into something strange and unique. “The art world didn’t necessarily take notice of him straight away, but he is so influential now,” Will Huxley says. “A lot of his costumes inspired people like McQueen and Galliano, and you can see the influence today, even on Drag Race. The weirder the costume, Leigh is in there somewhere.”

One of Bowery’s outfits had him encased head to toe in tight-fitting black latex, cinched at the waist. One shapely leg terminates in a high-heel platform shoe; the other ends in a stump like an elephant’s foot.

Bowery wore another of his emblematic costumes, called The Metropolitan, for the 1993 opening of a Lucian Freud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which included nude portraits of Bowery. This rather frightening outfit involves a German military helmet, an enormous skirt of floral sateen, and a face mask in the same fabric. Bowery’s eyes and mouth are visible, but every other part of his body is covered. The outfit was acquired in 1999 by the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), the first major institution to collect Bowery’s work.

Artist and academic Gary Carsley was a key figure behind a Bowery retrospective, Take a Bowery, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney in 2003. He regards Bowery as a vessel of cultural information, from the afternoon television programs he watched as a kid in Melbourne in the 1960s and ’70s, to the preoccupations and anxieties of the 1980s and early ’90s.

The cultural references are there if you know where to look. That elephant foot, Carsley says, resembles the ankle-less legs that Bowery would have seen on Astro Boy. The aggressive skirt on The Metropolitan is something Aunty Jack would wear.

Bowery found the almost perfect forum for his costumes and performances in the underground club scene. Clubs such as Danceteria in New York, the RoXY in Amsterdam, and Blitz and Kinky Gerlinky in London were a crucible for avant-garde art and fashion, and the larger clubs had budgets to produce performance art. Bowery was behind the opening of a famous, though short-lived club night, Taboo, in London’s Leicester Square. It became the subject of a 2002 musical with songs by Boy George, who played Bowery on stage in the 2003 Broadway season.

Not insignificantly, says Carsley, it was an era when young people could claim unemployment benefits and essentially underwrite their night life and creative ambitions. “Fun was a serious concern,” he says. “Young people had financial sovereignty – they could access what was then an affordable social benefit, which enabled enormous creative expression …

“Leigh was very fortunate in that he lived at a time when he could access social benefits – Australians can’t go to London anymore and do those kinds of things. He is very much, if you like, a person of his time.”

Bowery modified almost every aspect of himself, from his handwriting to his body shape, which he shoehorned into tight-fitting outfits and created outlandish, even alien, silhouettes. Piercings, full-face make-up, genital torture, cosplay and extreme corsetry were all part of the kit. He even changed his accent, Carsley says, opting for a worldly, unplaceable version of spoken English.

Carsley observes the presence of shame in these transformations, as Bowery sought to disguise or enhance his origins, his body and his level of education.

“Leigh, as a big boy, was always mindful that he didn’t fit into that idealised form of male handsomeness or beauty,” Carsley says. “He was incredibly self-conscious. There’s a key component in the diary where he decides to reshape his handwriting in order to better present as an intellectual.”

Bowery also responded to his HIV status through costume, in the years when a positive diagnosis was akin to a death sentence and the virus was surrounded by a hysterical level of homophobia. Carsley refers to a performance Bowery gave at the Serpentine Gallery in London in 1989 where he wore a full-body red outfit with a clown’s nose and eerie make-up.

“A lot of people may just look at the silhouette that is produced, but what is happening in this performance is a total suturing of the body and its orifices,” Carsley says. “You can understand how Leigh is one of the most consequential figures in the art of the late 1980s and early 1990s for the way in which his work directly channelled the anxieties and the fears and the vulnerability of a generation of queer men.”

Bowery entered the fine-art establishment with a dedicated show of his performance art at Anthony d’Offay Gallery in London in 1988. The next year he became an artist model for Lucian Freud. He posed for several nudes by the artist, including the large oil painting And the Bridegroom (1993), until recently on display at the Art Gallery of NSW. Bowery appears in these paintings fleshy and baldheaded, paradoxically stripped of the elaborate costumes and outlandish personas for which he was known.

Bowery and his close friend and collaborator Nicola Bateman married in May 1994. On New Year’s Eve that year, he died of complications from AIDS, at age 33.

How is Bowery remembered today, and what is his influence? Carsley says he sees Bowery’s presence in the earlier work of pop artist Troye Sivan. If he was working today, Bowery would have embraced the possibilities for image-making and self-projection on social media platforms such as TikTok.

In Melbourne, Bowery’s home town, his name is commemorated in the Bowery Theatre at the St Albans Community Centre, near where he grew up in Sunshine. The NGV this month hosts the inaugural Bowery Ball, a queer celebration of drag, burlesque and music. And the Huxleys continue to acknowledge Bowery in their performance and photographic work, often involving full-body costumes and glitter make-up. In their recent exhibition Bloodlines, shown at Abbotsford Convent as part of Melbourne’s Midsumma festival, they honoured queer artistic heroes who were lost to HIV/AIDS including Keith Haring, Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Tully and David McDiarmid. In their piece called Bowery, the Huxleys are pictured together in sequined bodysuits and full-face glitter make-up, and a kind of corseted waistcoat in patterned fabric.

“Artists like Leigh open doors for so many queer artists who come after them – they push you to be more extreme,” Will Huxley says. “We could never be as shocking as Leigh, but in some ways, we push back against the norm, just like Leigh was doing.

“It’s great to frighten the right people, I’ve always thought.”

The inaugural Bowery Ball is at the NGV on March 22, 2024.

This story is from the March issue of WISH.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout