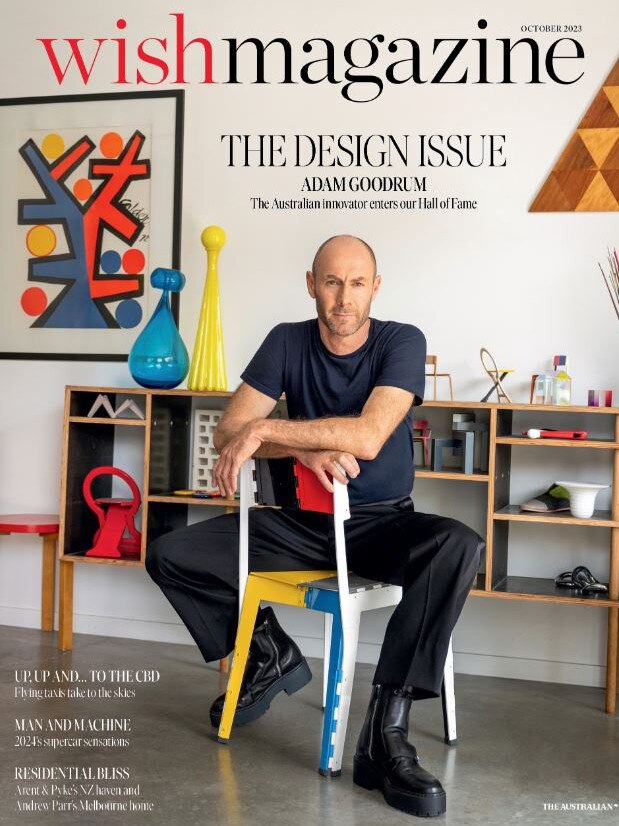

Adam Goodrum started tinkering in his parents’ shed; now he’s an award-winning innovator

If anyone has elevated design to the level of art, it’s Adam Goodrum. And yet the lauded industrial designer once thought his chosen career was second best.

Adam Goodrum still remembers the day and the name of the teacher who predicted his future career and shattered his teenage dreams in one go. The then 17-year-old wanted to be a painter, excelled at drawing and had just won an art competition. But a very intuitive Liz Rankin recognised his true talent and suggested he go in another direction.

“Liz was a very inspirational teacher and I remember her telling me when I won the art prize that I would one day make a great designer,” Goodrum recollects, laughing. “I was so mortified and devastated by that, because I didn’t want to be a bloody designer! Not that I am saying I am a great designer, but you know what I mean? I just remember in that moment that I was so defeated by her comment because all I wanted to be was an artist.”

The rest of Australia – and the world – should be grateful to Rankin as she helped put Goodrum on the path to becoming one of the country’s top furniture designers, who 34 years later has taken out scores of awards, and created innovative chairs, tables, cabinets and lounges that grace homes, restaurants and luxury boutiques.

His work has been exhibited at Milan’s Salone del Mobile, produced by international and Australian furniture companies, and been included in collections at London’s Design Museum, the National Gallery of Victoria, the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, the Art Gallery of Western Australia and the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney’s Ultimo.

It can also now be revealed that Goodrum has been admitted into the prestigious Design Institute of Australia (DIA) Hall of Fame. Founded 80 years ago, the DIA is the peak national professional body for the design industry and represents industrial, interior, graphic, digital, product, environmental, textile and fashion design. It has been honouring those at the top of their game with its Hall of Fame program for more than 27 years and its 130 inductees have included the likes of industrial designers Marc Newson and Carl Nielsen, fashion designers Collette Dinnigan and Jenny Kee, and graphic designers John and Ros Moriarty.

“Adam Goodrum is widely acknowledged as one of the most influential currently practising furniture designers in Australia,” DIA Hall of Fame chair James Harper tells WISH. “He has worked with some leading Australian and international furniture manufacturers and has really elevated their profile. He has created many brilliant, innovative products for them, and he also introduced a subtle Australian aesthetic to the world of design.”

Harper explains a DIA committee made the decision to admit eight designers, including Goodrum, Celina Clarke, Harley Anstee, Ian Wong, Maryanne Milazzo, Stafford Cliff, and the late Paul Cockburn and Richard Haughton James, to the Hall of Fame this year on a strict set of criteria. This includes not only being successful, winning critical acclaim but also being involved in education, mentoring the next generation as well as general character. “Adam is such a lovely person,” Harper says.

“He is by far the leading industrial designer in the country,” adds Richard Munao, founder and managing director of Australian furniture retailer Cult Design, who has worked with Goodrum for a number of years. “But for someone that is so very successful, he is a very humble person and acts like he is still trying to make the grade. That is what I love about him.

“We have got to the point now working together where his products are very successful and no other designer I work with rings me to say thank you, and yet he does. That is what makes him such a wonderful person beyond being just a great designer,” Munao adds.

That was the overwhelming response when WISH spoke to people in the industry who had worked with Goodrum; that he is a genuinely lovely guy who is easy to collaborate with. There is no ego and there was no shortage of people who were willing to talk about the designer. The only thing that may have superseded this aspect was praise of his talent.

“He is so creative, has out-of-the-box thinking and is playful,” says Arthur Seigneur, a French marquetry artisan who first met Goodrum after moving to Sydney from Paris in 2015. “All of his designs, all of the forms he creates, it’s like he brings the kid out from inside of you.”

Despite his preoccupation with painting and art, Goodrum has been designing products since he was a kid, he just didn’t really know it. He was born in Sydney in 1972 but grew up in Perth after his father, who was a scientist, got a job at a university in the Western Australian capital.

“I loved making things when I was young and because Perth was a bit of a big country town, everyone had these blocks of land and had a back shed so there was this real making culture,” Goodrum tells WISH. “There were fathers and grandfathers who had this great knowledge about making things. So myself and one particularly close friend of mine were always just in the shed making things and getting help from these people who were so knowledgeable with turning an axis on a lathe or something to do with fibreglassing.

“I used to think this was normal, but looking back now, if I had grown up in Sydney, I don’t think it would have happened because the blocks of land aren’t so big and not everyone has a back shed and that making culture. So I think I was really lucky to be honest.”

Like any good product designer, Goodrum’s first creations were born of necessity. He was a keen surfer, but the strong afternoon sea breeze known as the Fremantle Doctor meant it was too hard to ride his bike home carrying a surfboard under one arm. His solution was a trolley for the board that would attach to his bike. The wheels came from his mum’s laundry trolley and the wood from the back fence. She was not impressed.

As well as tinkering in the back shed, the teenager was also excelling at maths and art at school. That is when he came across Liz Rankin. “She was one of those teachers who would bring books in for you and at lunchtime you would go to work on pieces in her classroom, and she would show you techniques and always make an effort,” Goodrum recalls fondly. “They [teachers such as Liz Rankin] fully inform the direction of your life.”

Goodrum was still planning to study fine arts at university, but then he came across a new industrial design course and decided to “have a crack at it”. His choices were to go to Curtin University for three years or to head over to the east coast – where his grandparents still lived – and do the course at the University of Technology, Sydney.

“So being 17 and wanting to do something different, I decided to move to Sydney. I didn’t know anyone but did have a place to stay with my grandparents in Maroubra. I caught the Indian Pacific train over because it was the cheapest way to get there,” he recalls. “It was such an eye-opening experience, because the only ticket I could get was in the caboose and so I was with a bunch of pretty colourful people. There were scary-looking bikies either side of me, so when my mum was waving goodbye and crying, all these huge bikies who had their mums there too had their faces up against the glass and they were also crying. It was very funny.

“The bikie I sat next to ended up being this lovely big gentle guy. He brought Snakes and Ladders, so I just remember playing heaps of Snakes and Ladders with him over the next few days. He was on his way to Adelaide to become a tattoo artist or something like that.”

Goodrum made to it Sydney and loved it. He loved living and surfing in Maroubra and loved studying industrial design at UTS, then based in Balmain. In the third year of his course, he designed his first piece of furniture and something clicked. Rankin was spot on.

“It was the first time I actually designed a chair and that subject was taught by Carl Nielsen [a legendary Australian designer who is also in the DIA Hall of Fame]. So I decided to design a folding chair,” Goodrum recalls. “And for whatever reason, after that I became obsessed with designing furniture. I just loved the scale of it. And then there was also the movement of the folding chair, the articulation of coming from one form to another.”

Goodrum graduated in 1993 and there weren’t many job prospects at the time, but he kept doing projects, teaching at UTS and entering his work into competitions. He won many of them (“I was probably quite lucky,” he still contends) and managed to score an airfare to the prestigious Milan Furniture Fair (Salone del Mobile Milano), where it blew his mind to see this other world of industrial design existed outside of Australia.

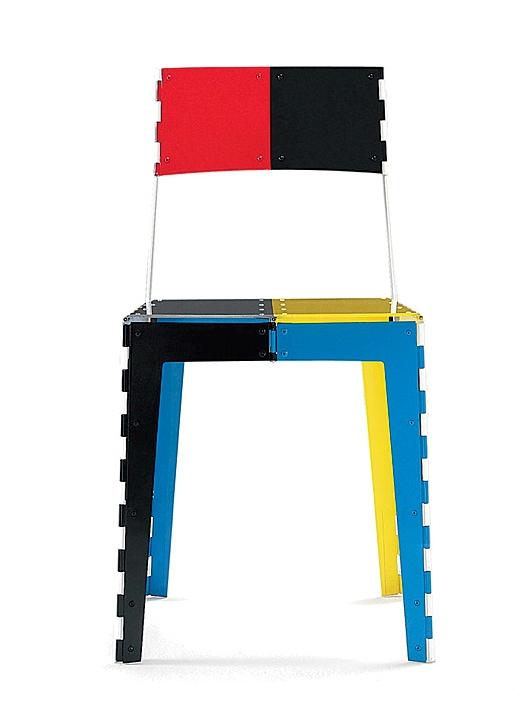

A few years later, his own product, the Stitch chair, was put into production by legendary Italian furniture maker Cappellini and then displayed in Milan.

The innovative new take on the folding chair meant it could be folded flat to 16mm – much thinner than usual – thanks to a unique hinge system. It is made of 10 pieces of painted aluminium “stitched together”.

The chair was selected in 2008 as one of the year’s best designs by London’s Design Museum, manufactured by Cappellini and ended up in the National Gallery of Victoria. “Marc Newson had designed for Cappellini but there have been no other Australian designers,” Goodrum says. “So that lifted my status in some ways and it validated what I was doing.”

Interior designer Sarah-Jane Pyke, one half of Sydney’s Arent & Pyke, saw Goodrum’s chair at Salone del Mobile in 2009. “As a design student, I worked with the Australian suppliers of Cappellini since 2000 and I still remember feeling so proud to see an Australian design on the world stage,” she tells WISH. “It was a real thrill seeing Adam’s chair on the Cappellini stand.”

While he was turning the folding chair world upside down with Stitch, Goodrum was still teaching at UTS (making use of the fabulous workshops on campus) and that was how he met Cult Design’s Richard Munao. Goodrum used to bring his students into the Australian retailer’s showroom in Chippendale to show them examples of classic, enduring furniture design.

“One day I finally asked Adam to design a lounge for us and he came back with four designs,” recalls Munao. “They were all so good that we put three into production.” Those lounges and armchairs were called Fat Tulip (“it looks like a beautiful tulip that is a bit fat”) and they became one of Cult Design’s biggest sellers.

Next was the solid wood Molloy dining chair, named after the unusual meeting of two rivers in Western Australia that form the Molloy River, 320km south of Perth, and where Goodrum and his father built an A-frame holiday house on Molloy Island.

“I actually asked him to design a dining table,” Munao laughs. “I said, ‘Adam, we have the best chairs in the world, but we don’t have a lot of offerings or flexibility with tables. Can you design a beautiful timber table for us?’

“Typically, Adam brings me the Molloy chair instead and I fall in love with it because it is a beautiful piece of art.”

The Molloy chair has now expanded into a collection that does have dining tables, as well as coffee tables and shelves. It is the most successful dining chair at Cult Design and is found in homes around the country, as well as in commercial settings and at Hermès boutiques, and it will soon be seen in Qantas flight lounges.

As well as designing pieces for Cult Design’s Nau brand (which stands for New Australian design), Goodrum also works with Munao on project commissions. This included designing the chairs for Peter Gilmore’s Quay restaurant at Circular Quay in 2018. “He’s so practical, while still creating beautiful things,” says Munao. “And he doesn’t design for Adam Goodrum – you wouldn’t recognise an Adam Goodrum chair. He designs for the client.”

Those projects and clients have included a Riddling Stool for Veuve Clicquot, one-off tables for Judith Neilson, outdoor furniture for retailer Tait, and a modular lounge called Big Talk for Swedish furniture brand Blå Station. He has also been working with Arthur Seigneur, a French marquetry artisan, since 2015 to create one-off pieces using the painstaking 17th-century technique of marquetry using hand-dyed straw instead of wood.

A “wild kaleidoscope of furniture ensured”, is how the Financial Times in London described the partnership, under the brand Adam & Arthur (also known as A&A), and those words are indeed apt when you are looking at their first piece, a cabinet titled Bloom, that is now housed at the NGV. A two-metre cabinet called Mother and Child created from 16000 flattened ribbons of rye straw won Furniture Design of the Year at the Dezeen Awards (UK). They also did a trunk for Louis Vuitton.

“I really enjoy it because it is a different creative outlet,” says the designer of working with Seigneur. “They are not commercial production pieces; they are one-offs, and we have complete creative freedom.” The admiration is mutual as Seigneur is also a fan of Goodrum. “Adam is very creative and he often pushes me out of my comfort zone,” the French-born artisan says. “There is often a bit of friction when you work with other designers or artists and it is often a bit tricky to collaborate on projects. But with Adam, it is always easy.”

Working with so many different talented people in Australia and around the world is one of the things Goodrum identifies as a highlight of his career. Undertaking such partnerships has also allowed the designer to still remain a designer; not getting caught up in the administration, project management, manufacturing or even running a showroom.

“I still really enjoy the creative pursuit of design,” Goodrum says, sitting in his small but beautiful light-filled studio in Waterloo, surrounded by colourful prototypes of his favourite works. “It is very rewarding to come up with an idea and work through and resolve any issues until you have a piece you can manufacture. Then it ends up on the showroom floor, and you may see it in a bar or in a house featured in a magazine.

“I was in the airport the other day and I walked into the Hermès boutique and I was like, ‘wow, there is my Molloy chair’. And then I went in and asked like an idiot if they minded if I took a picture of the chair. The staff were very nice and knew it was an Australian designer.”

As to being admitted into the Hall of Fame, Goodrum’s response is well, typical Goodrum. “It’s a real red-cheeks moment, isn’t it?” he says, smiling. “I had no idea, I really didn’t. Sarah-Jane from Arent & Pyke emailed me for a meeting and I thought it was for a table commission or something like that. And then Michael Bogle from the DIA was there at the meeting and I thought, ‘oh goodness, it’s a little bit serious’.

“Then they just revealed it and I was truly flabbergasted. To also learn about some of the other people who are on the list, I feel really quite humble to be honest.”

This story appears in the October issue of WISH Magazine, out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout