Designers Australia Awards 2022 celebrate the innovation of Australian design

Chosen from more than 300 entries, the four winners and 46 merit recipients reflected the outstanding state of Australian design.

The Design Institute of Australia celebrates the achievements of the country’s creative community in its annual awards, which recognise not only the products of good design but the people, processes and collaboration behind it. There are three unique categories: Place, Use and Interact, as well as the President’s Award, which recognises significant contribution to the industry. The four winners for 2022 and the 46 merit awards recipients were chosen from more than 300 entries.

PLACE

Kennedy Nolan for Always

A spectacular site is both a gift and a problem for new architecture. This is what Melbourne design firm Kennedy Nolan believes, and it was born out by a weekender project on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula.

This spectacular site was located on a cliff overlooking Western Port Bay and also had the obstacle of a house designed by noted mid-century architects Chancellor and Patrick. “Originally we wanted to preserve the house, but because of the unstable foundations and a very fragile geology, it had to be removed,” explains designer and co-founder of Kennedy Nolan, Patrick Kennedy.

“So the brief was for something that captured the warm and relaxed feeling of the old house, but with a bit more accommodation and the ability to host friends and family.” As well as the logistical challenges of building on a clifftop, there was the design challenge of letting the view overtake everything and the result being “single-orientation glassy boxes, which proliferate on such sites”.

Aware of this, Kennedy Nolan went about creating a house that did not have a huge amount of glass and would instead almost disappear into the surrounding landscape through the use of stone and wood.

“Our approach kept close to the well-understood architectural impulses of aspect, prospect and refuge,” explains Kennedy. “The prospect part was about capturing and framing the subtle, changing, beautiful views of Western Port Bay. We were keen to ensure that the house was sensitive, recessive and ultimately largely invisible by avoiding projecting forms and large expanses of glass. We instead emphasised an aspect dominated by an idealised, naturalistic landscape. The house was to be a refuge – a place to retreat to, a place with many places to be, finding spots following the path of the sun, courts and gardens to shelter from the wind coming off Western Port Bay.”

The architects primarily did this by using oiled cedar and blackbutt hardwood, earth-hued renders and pale green slate supports as materials. They also planted wild grasses on the roof. “We concentrated on a tonal palette drawn from earthy colours and natural ageing,” says Kennedy.

“We were consciously avoiding black and white and always imagining the materials over time, patinaing, fading or intensifying in colour, softening and losing their crisp edges.”

The team on the project included six design architects led by Kennedy and co-founder Rachel Nolan. Catherine Blamey was the project architect and Amanda Oliver took care of landscape gardening, while Jake Nash was the artist who worked on the house, called Always.

“The summer house is likely to become a more permanent residence over time and the name, Always, was suggested by a good friend of the owner, Jake Nash, who also designed the gates on the property,” Kennedy says.

“Always can mean a lot of things but the most important meaning is the reference to ‘Always was, always will be Aboriginal land’.” Kennedy Nolan, founded in 1999, has an approach to design that removes the distinction between interior and exterior architecture. It is dedicated to design that is highly responsive to its context and seeks to form a strong relationship with landscape.

“The separation of these disciplines is a new thing,” says Kennedy. “It’s not so much that we have dispensed with the separation, rather that we have drawn on the great tradition of fully integrated architecture and interiors exemplified by the great 20th century architects, such as Walter Burley and Marion Mahony Griffin, Gio Ponti and Alvar Aalto.”

The Design Institute of Australia is a fan of this approach, with the jury unanimously selecting Always, as the 2022 Place award winner. “Always blends with the physical environment through sensitive and reflective material selections to connect and engage with the landscape, architecture, our surroundings and history,” the jury notes.

“The interior is well articulated and draws on authentic materials appropriate for the setting. The design brings dark, quiet spaces to be a beach house, using materials to create intimacy, refuge and a sense of calm”.

The jury describes the home as a sanctuary respecting the landscape. “It is a well-conceived and realised project that shows a sophisticated response to the site, fusing human and natural spaces,” they say. Kennedy and his team were thrilled by the award and the jury’s remarks.

“Industry recognition by esteemed peers is a great reward for the time and effort put into projects,” he says. “As a profession of designers we seek happy and satisfied clients, but it is a privilege to have colleagues who have the same understanding of the process and recognise the effort involved.”

And the owner of Always was very happy with her house, says Kennedy: “The most gratifying element of our client’s reaction to the house and garden was the sense of familiarity and comfort she felt immediately – that the place feels right and is the place for her.”

-

USE

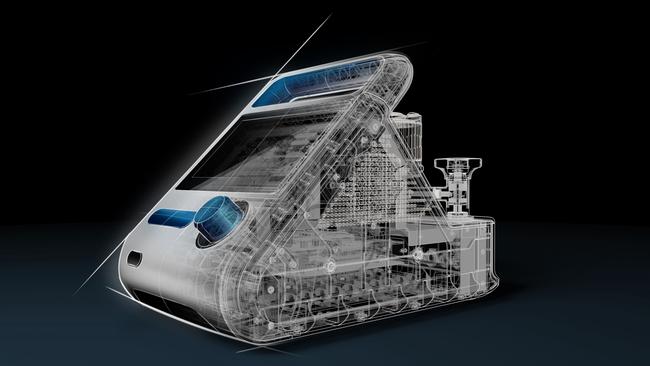

Cobalt Designs for Cobalt Design magAssist VAD Heart Pump

Design saves lives. It is a fairly obvious statement when you think about it, but the problem is we never do really think about the discipline in this way. We tend to seek out the people behind landmark architecture, iconic fashion that changed the way women dress or classic furniture that lasts for decades, but we don’t often look at medical devices and ask: who designed this? How did it come about?

The Design Institute of Australia wants to change that. It is raising awareness of the dramatic impact design can have on our lives by recognising Melbourne firm Cobalt Design for its part in producing a heart pump that keeps critically ill patients alive while they’re waiting for a heart transplant.

The firm, based in Melbourne, worked with a medical device startup in China called magAssist to create the VAD Heart Pump, which functions as a heart outside the body. MagAssist, founded by Professor Po-Lin Hsu and Lars Yang, wanted a pump that uses magnetic levitation to drive the device instead of a traditional mechanical interface between the pump and the motor.

“What it does is take over heart function,” explains Kynan Taylor, a mechanical engineer who led the project for Cobalt Design.

“So patients who are critically ill with heart failure or are having a heart procedure, where you basically need to replicate what the heart does outside the body. The blood comes out of the patient, through the pump and back into the patient.”

Taylor says using magnetic levitation to drive the pump means reduces the risk of blood being damaged or clotting as it gets pumped through the device and back into the patient.

“I use the analogy of phones that have a contactless charger compared to the standard charger,” adds Steve Martinuzzo, co-founder of Cobalt Design and principal on the MagAssist project.

“The contactless charger allows you to place the phone on it and it is a lot less intrusive compared to plugging in a cable.” Martinuzzo said they were introduced to Professor Hsu on a business trip in China in 2018 through a mutual contact and learned that the magAssist team was on a global hunt for a firm to develop the device around magnetic levitation.

They tendered for the project and won the contract. He says the magAssist VAD Heart Pump project came about because China has one of the highest incidences of treatable cardiovascular disease in the world but no one in the country was producing vitally needed artificial hearts.

“This product is going to address the problem of China having almost no access to these sorts of technologies because all the products are imported from high-cost countries,” the industrial designer explains. “So magAssist’s mission is to try to develop something that delivers the highest quality but at a more affordable price.”

Twenty-one staff from Cobalt Design working on the project for more than 4800 hours to help develop the device and completed the first prototype in just seven months.

There are more than 180 unique mechanical parts within the device’s console, motor and arm. Then came the design of the software interface – so that medical staff could use it – as well as product packaging. There was also a testing process that meant the design was tweaked multiple times along the way.

“It is a Class III medical device, which is the highest level, and that means it has the highest amount of testing and compliance requirements,” explains Taylor. “It covers the product, the effect on the patient and even the facility where the product is made, which has to undergo compliance testing.”

The magAssist VAD heart pump had to undergo lab-based tests, then animal trials using live sheep before it was tested on human beings. In August 2021, the first life was saved by the device when a woman in China was put on it for 12 days while waiting for a successful heart transplant. “It’s amazing,” she told medical staff. “The artificial heart immediately stopped the pain.” Martinuzzo, who founded Cobalt Design 26 years ago with Jack Magree, with third principal Warwick Brown coming on later, says his team is incredibly proud of the project. The heart pump is due to get authorisation from regulatory bodies to hit the market in China by the end of the year. There are also plans to take it global.

“We feel the design of the whole system, the control module, which is a console, with the integrated touchscreen and the way the pump and motor is integrated, the whole package, works much better than the competitors. That is something we are pretty proud of,” says Martinuzzo.

The Design Institute of Australia agrees, naming Cobalt Design’s device the winner of the 2022 Use Award. “The magAssist VAD Heart Pump is a brilliant product that results from a tight collaboration between engineering, design and medical science,” the jury says in its notes. “The devices have a functional purpose, making the concept of ‘aesthetic’ almost obsolete – provoking an exciting challenge for us to rethink the expanded role of design.”

Martinuzzo says he and the team who worked on the product were “pretty stoked” by the win, saying it was extra special given that the competition was judged by his peers. He paid tribute to the Design Institute of Australia for recognising the process of design and not just the end result.

He also believes there is not enough recognition in the wider Australian community of the impact that design has on their day-today lives – especially when it comes to products that are saving them.

“I think it is the bane of the industry,” Martinuzzo says. “I don’t think people think, wow, how did this come to be? Who brought this together? But from our point of view this project illustrates how good design is happening here in this country and that it can be exported to the world.”

-

INTERACT

Culture as Creative for Say It Loud, Naarm, Melbourne 2022

It was a comment by his niece that made architect Kholisile Dhliwayo start thinking about staging an exhibition highlighting female and diverse designers. His niece was studying architecture in Perth and mentioned that she never saw women in positions of authority in the big firms.

“She was one of my motivations,” the Zimbabweborn, Melbourne-trained and New York-based architect tells WISH. “A lot of the big architecture firms are quite male dominated and white, so she wasn’t seeing herself. I was also thinking of people I had mentored at university or classes and how they don’t see themselves in the work we are teaching or even the tutors.”

At the time, Dhliwayo was chatting to New York architect Pascale Sablan, who through her firm, Beyond The Built Environment, tries to address the inequities in the profession by what she calls the triple e’s plus c – engaging, educating, elevating and collaborating.

One of the ways she does this is through an exhibition that has gone around the world called SAY IT LOUD that highlights the work of BIPOC designers (Black, Indigenous and People of Colour) that is not in the public eye.

Sablan was seeking to extend her work into Australia and Dhliwayo suggested running the SAY IT LOUD exhibition in Melbourne to not only showcases the work of BIPOC architects and designers in Australia, but also highlight projects completed by female architects that may go unseen. Dhliwayo had spent the past decade working between Melbourne and New York and believed there was a definite need (a point that was reinforced by the experience of his niece).

“It was also an interesting way to get an education ourselves, and to know more about the women and BIPOC designers in Melbourne and Australia,” he says. “So that is why I reached out to Sandra Githinji as we had worked together previously.” Githinji runs her own multi-disciplinary design studio that explores the ways culture and history affect architecture and how people relate to it. The Kenyan-born, Melbourne-based designer is also a sessional lecturer of interior design at RMIT University.

“SAY IT LOUD has a very specific North American approach and Australia is very different from North America. The issues are different, the context is different, everything is different, so we had to tailor it to the Australian experience,” Dhliwayo says.

“It was important for us to localise it in a Melbourne context, and Pascale, Kholisile and I chatted about how to deliver an exhibition that couldn’t happen anywhere else in the world,” adds Githinji.

The first thing Githinji did was apply to 2022 Melbourne Design Week to stage the exhibition from March 17-26. She was successful, and it was decided it would be held at the No Vacancy Gallery in Jane Bell Lane in the city.

The next thing Githinji and Dhliwayo did was find someone locally to help create a concept and brand for the Melbourne version of SAY IT LOUD.

“It was important for us, working on this exhibition, which is about elevating and creating visibility for BIPOC designers, that we took every opportunity we could to also engage them in the production of the exhibition,” Githinji explains. “So working with graphic designer and branding consultant Edem Badu, who is of Ghanaian heritage, and her business Studio Badu was one of those ways of really actioning what we were saying people should be doing in the industry.”

Githinji, Dhliwayo, Badu and her team decided to call the exhibition SAY IT LOUD Naarm Melbourne, acknowledging the Indigenous place name of the city, as well to base the show around revealing structures that were hidden.

“That is a metaphor for BIPOC designers who might not be at the forefront,” Githinji says. “And through our process we were discovering them.” They also decided to include women because of the unequal representation in the profession, especially of BIPOC women.

“There are so many girls who study architecture – it’s 50/50 at architecture school, but when you actually go into practice you see those numbers decline significantly,” Githinji explains. “I am not particularly sure why that may be the case. Of course there is having a family and the social implications of that, but also the work environment is very male-centric and so it may deter women from continuing in the industry.”

She says children of immigrants face added hurdles as architecture and design are not seen as prestigious by their parents, unlike more traditional career paths.

“Speaking from an African background, often the creative fields are not really valued. Instead, it’s like, go be a doctor or a lawyer or an engineer. So there might not be enough of us seeing that these are opportunities we can pursue. I think being able to see architects and designers succeed in these fields is really important because it shows you that you can do it, and it shows our parents.”

The trio reached out to female and BIPOC designers and received 111 submissions. But they faced a uniquely Australian hurdle: our resistance to self-promotion, the tall poppy syndrome. “We had to really persuade these designers who were doing incredible work that they needed to show it off,” Githinji says. “I think Americans are better at putting themselves out there. That is something we found to be quite a challenge.”

They blacked out the exterior windows of the gallery and displayed the oversized words SAY IT LOUD, which helped with public engagement off the street (as did the adjacent coffee shop).

The exhibition was divided into three aisles and the centre – its heart – was devoted to First Peoples and Indigenous-led and focused projects. One aisle showcased artistic projects by designers with architectural backgrounds, such as furniture and objects; the other aisle displayed architecture.

SAY IT LOUD Naarm Melbourne also featured talks from architects about Indigenous design principles, as well as a mentoring program for 22 students/recent graduates. One of these was a woman who had come from Bangladesh, had a master’s degree and three years’ experience, but was struggling.

She loved the firm Woods Bagot but always thought any involvement was unattainable for her. “At the mentorship session, we got her partnered with someone who was at Woods Bagot and she was just beside herself,” recalls Githinji. “She couldn’t believe she was getting this access and she was having a conversation with someone who works there. Moments like that really validated what we were doing and the importance of that network, because for some it seems unattainable.”

The Design Institute of Australia also recognised the importance of SAY IT NOW Naarm Melbourne by naming it the winner of the 2022 Interact award.

“The principles and ethos driving this project are essential, highlighting the need to give recognition to the under-recognised, centring rather than marginalising voices,” the jury notes. “The project is well-positioned, articulated and reasoned, drawing upon postcolonial and gender theories to inform both approach and execution.”

-

PRESIDENT’S AWARD

Ros & John Moriarty for Balarinji

There is a good chance you have seen the work of John and Ros Moriarty’s design studio Balarinji but you just don’t know it. During their 40 years in business, the couple has been responsible for the iconic Indigenous art series on Qantas planes that have travelled around the world since 1994; the 2016 Rio Paralympics Australian team uniforms; the recently unveiled Australian Made logo; and multiple art installations on freeways, train stations, trucks, airports and in universities.

“It was very difficult for us to build an Indigenous design company when we started in 1983, as it was hard to get clients who understood what we were doing or a marketplace that was accepting of what we were doing,” Ros tells WISH. “But in our third and fourth decades, I think there has been a bigger groundswell of interest and support, especially in the past six to seven years.

“We see clients now who are much more interested in Indigenous art and culture. I think there is a generational change. I think our kids’ generation want to know more about us and they want to celebrate what this different sense of being Australian is.”

The story of how Balarinji came about is extraordinary and it starts with John’s life, which is even more extraordinary. He was born in 1938 in Borroloola, in the Gulf of Carpentaria in the Northern Territory.

“My early life was a tribal life because my mum spoke eight Aboriginal languages and we used to travel around by dugout canoes and hunt with spears,” he recalls. “But then one day my mum dropped me off at school and went to pick me up but I was gone, and my mum didn’t know where I was. I was taken by a missionary and put on the back of an army truck and taken to Alice Springs, put on a train to a place called Linden, just west of the Blue Mountains.”

John spent the remainder of his childhood there and in Adelaide, before getting an apprenticeship when he was 15. He went for a holiday in Alice Springs and unbeknown to him his mother had been sent to a hostel there.

“We met one day on the road,” he says. “She looked across at me, I was looking at her, and she walked over to me and said ‘Where are you from?’ and I said ‘Borroloola’ and she said ‘What’s your name?’ and I said ‘John Moriarty’, and she said ‘I’m your mother’.”

John’s heartbreaking experience of being taken away from his mother and his culture meant that when he and Ros had children, they wanted to ensure they were connected to Indigenous Australia and be given the experience John never had as a child growing up. “When they were small we made this commitment to always take them back to John’s community, because after he reconnected with his mum, he reconnected with his community, his language, his culture,” explains Ros.

“We wanted our children to feel a deep belonging in the Gulf of Carpentaria.” This translated into Ros and John silk screening some long-neck turtles on the bed linen and blinds in the bedroom of their first-born child to ensure he had a sense of belonging to the north of Australia, even though the family were living in Melbourne. When their second and third children were born, the couple would take all three back to John‘s home town as often as they could.

“We would take the kids up to the Gulf, and on the way we would camp overnight, John would sketch some things and I would mix some colours,” Ros recalls. “I don’t think we knew that one day we would have a design business; we were just trying to embed our own children in their heritage and wanting them to be comfortable in their skin. But then eventually we realised Australia was also searching for this kind of identity as well, so 40 years on here we are.”

John says the idea for Balarinji was to bring that Indigenous identity and culture to the forefront of Australian society.

“We wanted to make sure that people in Australia can connect with the Australian Aboriginal culture and that all Australians can learn about it,” he says. It was hard going in the first few years, but the turning point was being hired by Qantas in 1994 to paint a plane as part of the Flying Art Series. This meant not only did Australians see this incredible art by Balarinji around the country, it went around the world. Four more planes followed, and Balarinji also facilititated artist Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s work on a fifth plane that was launched in 2018.

“When the first aircraft flew in 1994, it was long before any talk of reconciliation,” recalls Ros. “There had been no bridge walks for reconciliation, no talk of a referendum vote or a voice. None of that had really happened when Qantas agreed with us to do the first aircraft. We definitely had those champion clients who took that extra step to look for the authenticity of the Aboriginal voice, and that hadn’t been heard very much in our public spaces in Australia up until that point.”

Several projects followed, with Balarinji growing and being commissioned to create uniforms for the Australian Rio Paralympic team, install a wide range of art on large-scale public infrastructure, parklands, national and international institutes, corporate offices and retail outlets.

The studio’s work is on display at The National Museum of Australia in Canberra, Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum, Flinders University Museum of Art and the Centre for Contemporary Graphic Design in Japan. Its most recent project was to redo the Australian Made logo after a new look in 2020 featuring golden wattle was scrapped due to its resemblance to the coronavirus.

Balarinji’s new logo – three boomerangs in the shape of a kangaroo – was designed by John and Kungarakan man Toby Bishop, a graphic designer and lead on the project. It was inspired by the phrase “yamulhu awara ambirriju” from John’s hometown Yanyuwa language.

It means “good country up ahead, good feeling for the future”, and embodies optimism from the spirit of country. It was this project as well as all the work undertaken by Balarinji over the past 40 years that led Designers Institute of Australia to name Ros and John Moriarty as recipients of the 2022 President’s Award for their contribution to the design profession and their approach to inclusivity and collaboration.

“Since 1983, Balarinji has been Australia’s foremost Indigenous design and strategy studio, working to deepen the understanding of Aboriginal Australia through major projects nationally,” the jury noted. “We see things from a fresh perspective through Ros and John Moriarty’s contributions. This shift in thinking driven by diversity and inclusivity is essential moving forward for all designers.”

For the couple, the award is testament to not only their team’s hard work, but to the way the design sector has moved forward to embrace the country’s Indigenous culture and also the clients who have championed their cause by hiring them.

As for the future, the Moriartys are optimistic. “We still have a really significant disparity in opportunity and so I hope that in the next 20 years design has a part to play in bringing visibility to the beauty and richness of the Aboriginal narrative,” Ros says. “And while social justice is an outcome we all want to see, there’s also the outcome of Australians being able to more richly celebrate who we are uniquely in the world.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout